1951 Tour de France

38th edition: July 4- July 29, 1951

Results, Maps, Stages with running GC, Photos and history

1950 Tour | 1952 Tour | Tour de France Database | 1951 Tour Quick Facts | 1951 Tour de France Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1951 Tour de France

Map of the 1951 Tour de France

Bill & Carol McGann's book The Story of the Tour de france, Vol 1: 1903 - 1975 is available as an audiobook here.

4,692 km ridden at an average speed of 32,694 km/hr.

123 starters and 66 classified finishers.

Fausto Coppi was too grief-stricken over the recent death of his brother Serse to effectively compete, leaving the way open for Hugo Koblet to ride one of the greatest races in Tour history.

This was the first time the Tour went over Mont Ventoux.

This was also the first Tour to leave France's hexagonal circumference and visit France's interior.

This was the first time since 1926 the the Tour hadn't started in or near Paris.

1951 Tour de France complete final General Classification:

Hugo Koblet (Switzerland): 142hr 20min 14sec

Hugo Koblet (Switzerland): 142hr 20min 14sec- Raphaël Géminiani (France) @ 22min

- Lucien Lazaridès (France) @ 24min 16sec

- Gino Bartali (Italy) @ 29min 9sec

- Stan Ockers (Belgium) @ 32min 53sec

- Pierre Barbotin (France) @ 36min 40sec

- Fiorenzo Magni (Italy) @ 39min 14sec

- Gilbert Bauvin (France East South-East) @ 45min 53sec

- Bernardo Ruiz (Spain) @ 45min 55sec

- Fausto Coppi (Italy) @ 46min 51sec

- Nello Lauredi (France) @ 57min 19sec

- Jean "Bim" Diederich (Luxembourg) @ 59min 29sec

- Marcel Demulder (Belgium) @ 1hr 4min 18sec

- Edward Van Ende (Belgium) @ 1hr 7min 18sec

- Serafino Biagioni (Italy) @ 1hr 8min 52sec

- Georges Meunier (France West South-West) @ 1hr 13min 36sec

- Roger Decock (Belgium) @ 1hr 13min 57sec

- Marcel Verschueren (Belgium) @ 1hr 14min 36sec

- Pierre Cogan (France West South-West) @ 1hr 15min 30sec

- Louison Bobet (France) @ 1hr 24min 9sec

- Jean-Marie Goasmat (France West South-West) @ 1hr 31min 27sec

- Aloïs De Hartog (Belgium) @ 1hr 35min 4sec

- Jean Dotto (France East South-East) @ 1hr 36min 23sec

- Georges Asechlimann (Switzerland) @ 1hr 39min 45sec

- André Rosseel (Belgium) @ 1hr 42min 22sec

- Bernard Gauthier (France) @ 1hr 51min 9sec

- Jean Robic (France Paris) @ 1hr 55min 35sec

- Hans Sommer (Switzerland) @ 1hr 58min 47sec

- Franco Franchi (Italy) @ 1hr 59min 13sec

- Roger Lévêque (France West South-West) @ 2hr 1min 51sec

- Lucien Teisseire (France) @ 2hr 8min 5sec

- Adolphe Deledda (France East South-East) @ 2hr 9min 29sec

- Vincent Vitetta (France East South-East) @ 2hr 9min 29sec

- Paul Giguet (France East South-East) @ 2hr 12min 23sec

- Marcel Huber (Switzerland) @ 2hr 13min 36sec

- Pierre Brambilla (France East South-East) @ 2hr 18min 29sec

- Louis Duprez (France Île de France North-West) @ 2hr 25min 44sec

- Andrea Carrea (Italy) @ 2hr 28min 1sec

- Roger Buchonnet (France East South-East) @ 2hr 31min 33sec

- Armand Baeyens (Belgium) @ 2hr 34min 4sec

- Édouard Muller (France) @ 2hr 39min 2sec

- Hilaire Couvreur (Belgium) @ 2hr 47min 1sec

- Germain Derijcke (Belgium) @ 2hr 47min 16sec

- Manolo Rodríguez (Spain) @ 2hr 49min 29sec

- Louis Caput (France Paris) @ 2hr 53min 38sec

- André Labaylie (France Île de France North-West) @ 2hr 54min 6sec

- Joseph Mirando (France East South-East) @ 2hr 58min 29sec

- Luciano Pezzi (Italy) @ 2hr 58min 38sec

- Joseph Morvan (France West South-West) @ 2hr 59min 11sec

- Gottfried Weilenmann (Switzerland) @ 3hr 1min 15sec

- Gino Sciardis (France Île de France North-West) @ 3hr 9min 0sec

- Ettore Milano (Italy) @ 3hr 11min 3sec

- Angelo Colinelli (France East South-East) @ 3hr 11min 58sec

- Virgilio Salimbeni (Italy) @ 3hr 12min 23sec

- Willy Kemp (Luxembourg) @ 3hr 19min 2sec

- Jean Baldassari (France) @ 3hr 20min 40sec

- Roger Walkowiak (France West South-West) @ 3hr 21min 30sec

- Dalmacio Langarica (Spain) @ 3hr 24min 24sec

- Francisco Masip (Spain) @ 3hr 40min 13sec

- Léo Weilenmann (Switzerland) @ 3hr 48min 32sec

- Jean Guéguen (France) @ 3hr 49min 47sec

- Aloïs Van Steenkiste (Belgium) @ 3hr 56min 5sec

- Jean Carle (France Paris) @ 4hr 8min 53sec

- Émile Baffert (France East South-East) @ 4hr 45min 26sec

- Manuel Mayen (North Africa) @ 4h 56min 59sec

- And-el-Kader Zaaf (North Africa) @ 4hr 58min 18sec

Climbers' Competition:

Raphaël Géminiani (France): 66 points

Raphaël Géminiani (France): 66 points- Gino Bartali (Italy): 59

- Fausto Coppi (Italy), Hugo Koblet (Switzerland), Bernardo Ruiz (Spain), each at 41 points.

- Lucien Lazaridès (France): 37

- Jean Robic (France Paris): 23

- Bernard Gauthier (France): 22

- Jean Dotto (France East South-East): 22

- Robert Buchonnet (France East South-East): 18

Team Classification:

- France: 426hr 47min 36sec

- Belgium @ 44min 37sec

- Italy @ 1hr 22min 16sec

- France East South-East @ 1hr 48min 0sec

- France West South-West @ 2hr 15min 38sec

- Switzerland @ 2hr 49min 55sec

- Spain @ 4hr 45min 19sec

- France Île de France North-West @ 5hr 30min 39sec

- France Paris @ 6hr 5min 29sec

1951 Tour stage results with running GC:

Stage 1: Wednesday, July 4, Metz - Reims, 185 km

- Giovanni Rossi: 5hr 23min 10sec

- Attilio Redolfi s.t.

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Sylvio Pedroni s.t.

- Marcel Huber s.t.

- Jean-Apo Lazarides s.t.

- Jacques Marinelli @ 43sec

- Robert Desbats s.t.

- Louis Caput @ 52sec

- Gino Sciardis s.t.

GC after Stage 1:

- Giovanni Rossi: 5hr 23min 10sec

- Attilio Redolfi @ 30sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 1min

- Sylvio Pedroni s.t.

- Marcel Huber s.t.

- Jean-Apo Lazarides s.t.

- Jacques Marinelli @ 1min 43sec

- Robert Debats s.t.

- Louis Caput @ 1min 52sec

- Gino Sciardis s.t.

Stage 2: Thursday, July 5, Reims - Gent, 228 km

- Jean "Bim" Diederich: 6hr 28min 54sec

- Stan Ockers @ 2min 41sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 4min 2sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 4min 21sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 50sec

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Jean Baldassari s.t.

- André Rosseel s.t.

- Germain De Rijcke s.t.

- José Beyaert s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Jean "Bim" Diederich: 11hr 53min 56sec

- Stan Ockers @ 2min 41sec

- Attilio Redolfi @ 3min 28sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 4min 2sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 4min 21sec

- Robert Desbats @ 4min 41sec

- Jacques Marinelli s.t.

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 4min 42sec

- Sylvio Pedroni s.t.

- Marcel Huber s.t.

Stage 3: Friday, July 6, Gent - Le Tréport, 219 km

- Georges Meunier: 7hr 4min 14sec

- Giovanni Rossi @ 30sec

- Willy Kemp @ 1min

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Gérard Peters @ 1min 58sec

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Raymond Guegan s.t.

- Jean Baldassari s.t.

- Jean Delahaye s.t.

- Marcel Michel s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Jean Diederich: 19hr 8min 1sec

- Stan Ockers @ 2min 41sec

- Georges Meunier @ 2min 52sec

- Attilio Redolfi @ 3min 28sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 3min 44sec

- Giovanni Rossi @ 3min 47sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 4min 21sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 4min 27sec

- Willy Kemp @ 4min 36sec

- Robert Desbats @ 4min 41sec

Stage 4: Saturday, July 7, Le Tréport - Paris, 188 km

- Roger Levêque: 4hr 42min 15sec

- Jean Baldassari @ 52sec

- Hilaire Couvreur s.t.

- Dominique Forlini s.t.

- Lucien Teisseire s.t.

- Jean-Apo Lazarides @ 1min 49sec

- Raymond Guegan @ 3min 21sec

- Isidore De Rijcke s.t.

- Louis Deprez s.t.

- André Labeylie s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Jean Diederich: 23hr 45min 44sec

- Roger Levêque @ 2min 13sec

- Jean Baldassari @ 2min 21sec

- Stan Ockers @ 2min 41sec

- Georges Meunier @ 2min 52sec

- Attilio Redolfi @ 3min 28sec

- Lucien Teisseire @ 3min 35sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 3min 44sec

- Giovanni Rossi @ 3min 47sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 4min 21sec

Stage 5: Saturday, July 8, Paris - Caen, 215 km

- Serafino Biagioni: 6hr 9min 34sec

- Serge Blusson @ 10min 29sec

- Fiorenzo Magni s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Gino Sciardis s.t.

- Henk Faanhof s.t.

- Gerrit Voorting s.t.

- Wim Van Est s.t.

- Jean Robic s.t.

GC after stage 5:

- Serafino Biagioni: 30hr 5min 11sec

- Jean Diderich @ 1min 6sec

- Roger Levêque @ 3min 19sec

- Jean Baldassari @ 3min 27sec

- Stan Ockers @ 3min 47sec

- Georges Meunier @ 3min 58sec

- Attilio Redolfi @ 4min 34sec

- Lucien Teisserire @ 4min 41sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 4min 50sec

- Giovanni Rossi @ 4min 53sec

Stage 6: Monday, July 9, Caen - Rennes, 182 km

- Edouard Muller: 5hr 22min 10sec

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Wim Van Est s.t.

- Andréa Carrea s.t.

- Roger Levêque s.t.

- Marcel Demulder @ 3min 11sec

- Jean-Marie Cieleska s.t.

- Robert Castellin s.t.

- Hans Sommers @ 5min 45sec

- Gino Sciardis s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Roger Levêque: 35hr 30min 40sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 1min 1sec

- Edouard Muller @ 4min 37sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 5min 25sec

- Andréa Carrea @ 8min 21sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 8min 22sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 9min 39sec

- Robert Castelin @ 10min 20sec

- Jean Diederich @ 10min 45sec

- Wim Van Est @ 11min 9sec

Stage 7: Tuesday, July 10, La Guerche - Angers 85 km Individual Time Trial

- Hugo Koblet: 2hr 5min 40sec

- Louison Bobet @ 59sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 4sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 2min 52sec

- Piere Barbiotin @ 3min 53sec

- Jean Goldschmit @ 5min 3sec

- Gino Bartali @ 5min 14sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 5min 41sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 5min 58sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 6min 15sec

GC after Stage 7:

- Roger Levêque: 37hr 43min 53sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 1min 19sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 4sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 7min 47sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 8min 4sec

- Louison Bobet @ 8min 31sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 9min 6sec

- Edouard Muller @ 9min 20sec

- Andréa Carrea @ 9min 38sec

Stage 8: Wednesday, July 11, Angers - Limoges, 241 km

- André Rosseel: 7hr 8min 20sec

- Nello Lauredi s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 57sec

- Gerrit Voorting s.t.

- Jean Diederich s.t.

- Pierre Cogan s.t.

- Maurice Diot s.t.

- Robert Desbats s.t.

- Alois De Hertog s.t.

- Aloïs Van Steenkiste

GC after Stage 8:

- Roger Levêque: 44hr 57min 21sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 1min 19sec

- Jean Diderich @ 6min 44sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 4sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 7min 47sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 8min 4sec

- Louison Bobet @ 8min 31sec

- Aloïs Van Steenkiste @ 9min

- Fausto Coppi @ 9min 6sec

Stage 9: Friday, July 13, Limoges - Clermont Ferrand, 236 km

![]() Major ascents: Moreno, Ceyssat

Major ascents: Moreno, Ceyssat

- Raphaël Géminiani: 6hr 59min 40sec

- Jean Goldschmit @ 52sec

- Stan Ockers @ 1min 14sec

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Raoul Remy s.t.

- Jean Robic s.t.

- Gerrit Voorting s.t.

- Serafino Biagioni s.t.

- Willy Kemp s.t.

- Pierre Cogan s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Roger Levêque: 51hr 58min 16sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 1min 19sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 6min 44sec

- Jean Diederich @ 6min 45sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 4sec

- Sarfino Biagioni @ 7min 47sec

- Louison Bobet @ 8min 31sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 9min 6sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 10min 54sec

Stage 10: Saturday, July 14, Clemont Ferrand - Brive la Gaillarde, 216 km

![]() Major ascents: Croix Morand, Roche Vendeix, Puy de Bort

Major ascents: Croix Morand, Roche Vendeix, Puy de Bort

- Bernardo Ruiz: 6hr 35min 15sec

- Marcel Verschueren @ 1min 38sec

- Bernard Gauthier @ 2min 25sec

- Armand Baeyens s.t.

- Serafino Biagioni @ 6min 44sec

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Gérard Peters @ 7min 27sec

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Roger Decock s.t.

- Wim Van Est s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Roger Levêque: 58hr 40min 57sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 36sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 6min 14sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 6min 44sec

- Jean Diederich @ 6min 45sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 4sec

- Serafno Biagioni s.t.

- Louison Bobet @ 8min 31sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 9min 6sec

Stage 11: Sunday, July 15, Brive la Gaillarde - Agen, 177 km

This is the legendary stage where Hugo Koblet attacked with 135 km to go and single-handedly held off Coppi, Bobet, Bartali, Magni, Géminiani and Robic. Cycling's finest worked together but Koblet only increased his lead as they chased. It was one of the greatest rides in cycling history.

- Hugo Koblet: 4hr 32min 41sec

- Marcel Michel @ 3min 35sec

- Gérard Peters s.t.

- Germain De Rijcke s.t.

- Jean Robic s.t.

- Louis Caput s.t.

- Wout Wagtmans s.t.

- Manuel Rodriguez s.t.

- Bernardo Ruiz s.t.

- Gerrit Voorting s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Roger Levêque: 63hr 16min 13sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 36sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 3min 27sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 6min 14sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 6min 44sec

- Jean Diederich @ 6min 45sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 4sec

- Serafino Biagioni s.t.

- Louison Bobet @ 8min 31sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 9min 6sec

Stage 12: Monday, July 26, Agen - Dax, 185 km

- Wim Van Est: 5hr 25sec

- Louis Caput s.t.

- Jacques Marinelli s.t.

- Gerrit Voorting s.t.

- Edouard Muller s.t.

- Hans Sommers s.t.

- André Labeylie s.t.

- Georges Meunier s.t.

- Maurice Demulder s.t.

- Joseph Morvan s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 18min 16sec

- Jean Robic s.t.

GC after stage 12:

- Wim Van Est: 68hr 30min 24sec

- Georges Meunier @ 2min 29sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 3min 13sec

- Roger Levêque @ 4min 30sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 5min 6sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 57sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 10min 44sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 11min 14sec

- Jean Diederich @ 11min 15sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 11min 34sec

Stage 13: Tuesday, July 17, Dax - Tarbes, 201 km

![]() Major ascent: Aubisque

Major ascent: Aubisque

- Serafino Biagioni: 5hr 47min 57sec

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Nello Lauredi s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Maurice Diot @ 7min 55sec

- Pierre Brambilla s.t.

- Edward Ven Ende s.t.

- Gino Bartali @ 9min 15sec

- Adolphe Deledda s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Gilbert Bauvin: 74hr 22min 37sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 6min 18sec

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Georges Meunier @ 10min 5sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 12min 56sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 13min 19sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 13min 21sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 15min 43se

- Lucien Lazarides @ 16min 33sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 18min 35sec

Stage 14: Wednesday, July 18, Tarbes - Luchon, 142 km

![]() Major ascents: Tourmalet, Aspin, Peyresourde

Major ascents: Tourmalet, Aspin, Peyresourde

- Hugo Koblet: 4hr 41min 41sec

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Gino Bartali @ 2min 4sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 2min 48sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 6min 10sec

- Stan Ockers @ 7min 26sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 8min 59sec

- Louison Bobet s.t.

- Edward Van Ende s.t.

- Alois De Hertog s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Hugo Koblet: 79hr 16min 14sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 21sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 32sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 5min 9sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 29sec

- Georges Meunier @ 12min 15sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 12min 53sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Nello Lauredi @ 13min 40sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 16min 17sec

Stage 15: Thursday, July 19, Luchoin - Carcassonne, 213 km

![]() Major ascents: Ares, Portet d'Aspet. Stage places 5 through 16 were given same time and place.

Major ascents: Ares, Portet d'Aspet. Stage places 5 through 16 were given same time and place.

- André Rosseel: 6hr 22min 1sec

- Roger Decock @ 12sec

- Maurice Diot s.t.

- Louis Caput s.t.

- Paul Giguet s.t.

- Jean Dotto s.t.

- Lucien Teisseire s.t.

- Germain De Rijcke s.t.

- Edward Van Ende s.t.

- Pierre Brambilla s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Hugo Koblet: 85hr 43min 23sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 21sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 32sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 5min 9sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 29sec

- Serafino Biagioni @ 11min 21sec

- Georges Meunier @ 12min 15sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 12min 53sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Nello Lauredi @ 13min 40sec

Stage 16: Friday, July 20, Carcassonne - Montpellier, 192 km

- Hugo Koblet: 5hr 27min 14sec

- Jacques Marinelli s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Lucien Lazarides s.t.

- Pierre Barbotin s.t.

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 14sec

- André Labeylie s.t.

- Louison Bobet s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 5min 34sec

- Marcel Verschueren s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Hugo Koblet: 91hr 9min 37sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 1min 32sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 8min 29sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 13min 21sec

- Gino Bartali @ 18min 7sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 20min 14sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 22min 48sec

- Louison Bobet @ 22min 54sec

- Marcel Demulder @ 23min 48sec

- Stan Ockers @ 25min 19sec

Stage 17: Sunday, July 22, Montpellier - Avignon, 224 km

![]() Major ascent: Mont Ventoux

Major ascent: Mont Ventoux

- Louison Bobet: 7hr 24min 44sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 50sec

- Gino Bartali @ 56sec

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Lucien Lazarides s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 1min 15sec

- Alois De Hertog @ 1min 26sec

- Edward Van Ende s.t.

- Adolphe Deledda @ 4min 50sec

GC after Stage 17:

- Hugo Koblet: 98hr 35min 17sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 1min 32sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 49sec

- Gino Bartali @ 17min 47sec

- Louison Bobet @ 20min 58sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 22min 12sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 24min 8sec

- Stan Ockers @ 25min 38sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 28min 20sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 31min 49sec

Stage 18: Monday, July 23, Avignon - Marseille, 173 km

- Fiorenzo Magni: 4hr 56min 46sec

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Gino Sciardis s.t.

- Roger Buchonnet s.t.

- Georges Meunier s.t.

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Hilaire Couvreur s.t.

- Pierre Barbotin s.t.

- Joseph Morvan s.t.

- Serafino Biagioni s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Hugo Koblet: 103hr 36min 37sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 1min 32sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 49sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 17min 38sec

- Gino Bartali @ 17min 47sec

- Stan Ockers @ 20min 34sec

- Louison Bobet @ 20min 58sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 23min 46sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 24min 8sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 26min 34sec

Stage 19: Tuesday, July 24, Marseille - Gap, 208 km

![]() Major ascents: Sagnes, Sentinelle

Major ascents: Sagnes, Sentinelle

- Armand Baeyens: 7hr 15min 41sec

- Gino Bartali @ 1min 33sec

- Fiorenzo Magni s.t.

- Jean Robic s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Jacques Marinelli s.t.

- Pierre Cogan s.t.

- Nello Lauredi s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Hugo Koblet: 110hr 53min 51sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 1min 32sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 7min 49sec

- Gino Bartali @ 16min 57sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 17min 58sec

- Stan Ockers @ 20min 34sec

- Louison Bobet @ 21min 18sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 23min 46sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 24min 8sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 26min 34sec

Stage 20: Wednesday, July 25, Gap - Briançon, 165 km

![]() Major ascents: Vars, Izoard

Major ascents: Vars, Izoard

- Fausto Coppi: 5hr 34min 4sec

- Roger Buchonnet @ 3min 43sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 4min 9sec

- Gino Bartali @ 7min 36sec

- Stan Ockers @ 9min 3sec

- Lucien Lazarides s.t.

- Jean Robic @ 11min 39sec

- Gilbert Bauvin s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 11min 46sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Hugo Koblet: 116hr 32min 4sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 9min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 12min 43sec

- Gino Bartali @ 20min 24sec

- Stan Ockers @ 25min 28sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 30min 41sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 31min 16sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 34min 41sec

- Louison Bobet @ 37min 23sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 28min 23sec

Stage 21: Thursday, July 26, Briançon - Aix les Bains, 201 km

![]() Major ascents: Lautaret, Laffrey, Porte, Cucheron, Granier

Major ascents: Lautaret, Laffrey, Porte, Cucheron, Granier

- Bernardo Ruiz: 6hr 45min 24sec

- Jean Robic @ 1min 46sec

- Pierre Cogan s.t.

- Jean Dotto s.t.

- Bernard Gauthier s.t.

- Jean-Marie Goasmat @ 6min 33sec

- Stan Ockers @ 6min 38sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Adolphe Deledda s.t.

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Hugo Koblet: 123hr 24min 6sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 9min 2sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 12min 43sec

- Gino Bartali @ 20min 4sec

- Stan Ockers @ 25min 28sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 30min 41sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 31min 48sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 32min 43sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 34min 41sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 38min 23sec

Stage 22: Friday, July 27, Aix les Bains - Geneva 97 km Individual Time Trial

- Hugo Koblet: 2hr 39min 45sec

- Roger Decock @ 4min 50sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 4min 59sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 5min 43sec

- Stan Ockers @ 6min 25sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 7min 28sec

- Gino Bartali @ 8min 5sec

- Nello Lauredi @ 8min 7sec

- Lucien Lazarides @ 10min 33sec

- Joseph Morvan @ 11min 26sec

GC after Stage 22:

- Hugo Koblet: 126hr 2min 51sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 22min

- Lucien Lazarides @ 24min 16sec

- Gino Bartali @ 29min 9sec

- Stan Ockers @ 32min 53sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 36min 40sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 41min 24sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 45min 53sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 45min 55sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 46min 51sec

Stage 23: Saturday, July 28, Geneva - Dijon, 197 km

- Germain De Rijcke: 6hr 11min 32sec

- Lucien Teisseire s.t.

- Adolphe Deledda s.t.

- André Rosseel s.t.

- Abdel-Kader Zaaf s.t.

- Jean Mayen s.t.

- Joseph Mirando s.t.

- Pierre Brambilla s.t.

- Roger Walkowiak @ 21sec

- Stan Ockers @ 5min 52sec

GC after Stage 23:

- Hugo Koblet: 132 hr 20min 15sec

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 22min

- Lucien Lazarides @ 24min 16sec

- Gino Bartali @ 29min 9sec

- Stan Ockers @ 32min 53sec

- Pierre Barbotin @ 36min 40sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 41min 24sec

- Gilbert Bauvin @ 45min 53sec

- Bernardo Ruiz @ 45min 55sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 46min 51sec

Stage 24 (Final Stage): Sunday, July 29: Dijon - Paris, 322 km

Places 7 - 63 all given same time and place.

- Adolphe Deledda: 9hr 58min 19sec

- Fiorenzo Magni s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 1min 40sec

- Jean Robic s.t.

- Germain De Rijcke s.t.

- Emile Baffert s.t.

- André Labeylie s.t.

- Louis Deprez s.t.

- Jean Carle s.t.

- Louis Caput s.t.

The Story of the 1951 Tour de France:

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Tour de France", Volume 1 If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make ethe purchase easy.

The Daily Peloton website generously let me incorporate their 1951 Tour history and pictures into my own 1951 Tour story. I can't thank writer Podofdonny enough. He not only let me take liberally from his text, he let me use the pictures from his collection. The magazine photos are from Picture Post 1951. The bike business sure has some wonderful people.

For the first time the Tour headed inland to the Massif Central, crossed Mont Ventoux and, unusually, started outside Paris. Until 1951 the Tour's route had followed the hexagonal outline of France, never venturing into the interior. Only one other time, in 1926, had the race not started in Paris. The 123 riders from 12 national and French regional teams set off on the 4,692 kilometer, 24-stage race going counter-clockwise (Pyrenees first) around France starting in Metz.

|

||

The 1951 Tour de France route with its new detour into the center of France. |

||

We saw that in 1950 Swiss cycling had hit a new peak with the powerful twin engines of Ferdy Kübler and Hugo Koblet.

Kübler and Koblet could hardly have been more opposite. Kübler with his large nose and smile that turned into a demonic grin when he was making a big effort was known as the "pedaling madman" or the "the Eagle of Adilswil" for the Swiss village where he grew up. Hugo Koblet was tall, beautiful like a Greek god, with undulating fair hair, clear eyes, and inimitable elegance. He was incredibly gifted. Koblet was nicknamed the "Pédaleur de Charme". L'Equipe called him "Apollo on a Bike". His effortless grace on a bicycle combined with his natural talent was in marked contrast to Kübler, who would thrash his bike into submission, white foam around his mouth, pedaling with an ungainly riding style.

Koblet made his name as a pursuiter. He was Swiss champion at the discipline every year from 1947 to 1954 and was the bronze medalist at the World Championships in 1947. In 1951 he was offered a place on the Swiss Tour team that did not include Kübler. With Koblet clearly the finest rider on the team, there would be no competition for team leadership.

Ferdy Kübler had a standout year in 1951, winning the World Championship, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, the Fleche Wallonne, and the Tours of Romandie and Switzerland. He also came in third in the Giro. Even without riding the Tour, Kübler's 1951 would have been a fine career for almost any other racer. It has been suggested that had Kübler ridden the Tour in 1951, he was to ride in support of Koblet. For that reason it was said that Kübler declined to ride the Tour that year.

Koblet's main rival should have been Fausto Coppi, but the legendary Italian had just buried his beloved brother Serse. That loss left Coppi in no condition for the Tour. Coppi's terrible grief manifested itself at one point in the Tour in a wave of nausea and vomiting.

The French had a team that could win the Tour, with Jean Robic, Louison Bobet and Raphaël Géminiani. Bobet was in good form. He was Champion of France and had won Milan–San Remo and the Criterium National. The French papers said Bobet was the favorite to win the Tour. Team strategy decided that Géminiani and Bobet would be co-leaders of the French team.

The Belgians had Stan Ockers leading their team. This was a superb field. Whoever wanted to win this Tour would have to earn it. Nobody expected Koblet, the playboy from Zurich, to be the final victor.

Among the French regional teams was Afrique du Nord, a team made of Algerian and Moroccan riders, which included Algerian Abdel Khader Zaaf, who had become something of a celebrity with the fans in 1950.

Koblet showed either his bravado or naivete on stage 1 when he attacked nearly from the gun. He was brought back by the peloton after 40 kilometers of chasing. A cautious truce fell between the main contenders.

Over the next 5 stages they crossed northern France. While the main contenders eyed each other cautiously, lesser riders took the glory and gained real time. In stage 4 Roger Levêque, a rider for the regional West-South-West team, broke away with 85 kilometers to go. His stage win earned him second place in the overall standings, a little over 2 minutes behind the Yellow Jersey, Bim Diederich of Luxembourg. By the end of stage 6 Levêque was in Yellow, having joined the day's winning break. The highest placed of the fancied contenders, Stan Ockers, was more than 13 minutes back.

Stage 7, an 85-kilometer Individual Time Trial between La Guerche and Angers, let Koblet lay down the gauntlet. He won the stage with an average speed of 40.583 kilometers an hour and moved up into third place on the General Classification.

|

||

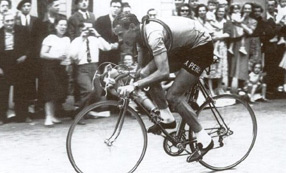

Hugo Koblet riding in his economical, compact style. |

||

The results of the time trial were not so clear at first. The timekeeper initially believed that Louison Bobet had bested Koblet. By his calculations Levêque was no longer the Yellow Jersey. Koblet and his manager protested that evening to Tour boss Jacques Goddet. Their concern was probably not that Levêque would unjustly lose his Yellow Jersey. They didn't want to give Bobet, a real threat to win the Tour, an unearned stage victory and a free full minute in bonus time. They showed Goddet that by virtue of the intermediate timings, Bobet's winning was a near impossibility. The timekeeper relented, Koblet was given the stage win, and Levêque had his Yellow Jersey returned. Koblet's pace was so fast that 12 riders were eliminated from the Tour for failing to make the time cutoff.

The stage results:

- 1. Hugo Koblet: 2 hours 5 minutes 40 seconds

- 2. Louison Bobet @ 59 seconds

- 3. Fausto Coppi @ 1 minute 4 seconds

- 4. Fiorenzo Magni @ 2 minutes 52 seconds

The General Classification was now:

- 1. Roger Levêque

- 2. Gilbert Bauvin @ 1 minute 19 seconds

- 3. Hugo Koblet @ 7 minutes 2 seconds

- 7. Louison Bobet @ 8 minutes 31 seconds

- 8. Fausto Coppi @ 9 minutes 6 seconds

- 11. Fiorenzo Magni @ 10 minutes 54 seconds

During the next 3 stages the race headed inland for the first time in Tour history and into the leg-sapping Massif Central. Raphaël Géminiani won stage 9. Ockers, Koblet and the rest of those who dreamed of Yellow in Paris finished just a little over a minute behind him. The next day, stage 10, Spanish rider Bernardo Ruiz was first over all 3 of the day's major rated climbs and then won the stage. He left most of the field over 7 minutes behind.

After stage 10, Levêque was still leading. Bauvin had closed to within 36 seconds of him. The eventual King of the Mountains winner, Raphaël Géminiani, was showing fine form and moved into fourth place overall at 6 minutes, 44 seconds. Koblet dropped back to sixth at 7 minutes, 7 seconds. Bobet, Coppi and Magni were clustered just a few minutes behind Koblet.

It was in stage 11 that Hugo Koblet became a Tour immortal. It was a transitional stage before the Pyrenees and the Alps. Conventional wisdom said that an attack here would be the equivalent of suicide. Koblet had no time for conventional wisdom. On the thirty-seventh kilometer with 135 kilometers to go, in baking hot weather, he escaped the peloton on a small climb with the French rider Louis Deprez.

The other contenders for the General Classification must have smiled to themselves at this act of folly. The Tour rookie was going to burn himself out with both the Pyrenees and the Alps yet to be climbed. After a few kilometers Deprez found Koblet's pace too fast and dropped back. The Swiss rider was now on his own. However, when the gap rose to 4 minutes the laughter ceased and the peloton began to chase back in earnest.

Bobet flatted. The 2 members of the French team who were working the hardest to pull the fleeing Swiss back were told to halt their efforts and go back to pace Bobet back up. Until Bobet and his teammates rejoined the peloton, only the Italians were working to recapture Koblet. The chase lost its momentum for a while.

With 70 kilometers to go Koblet still had a 3 minute lead. Now the big guns were taking serious turns at the front of the peloton. Coppi, Bartali, Bobet, Robic, Ockers, Magni, and Géminiani added their weight to the chase. The finest riders in the world were cooperating with each other, taking pulls at the front of the chasing peloton. Yet this group of cycling immortals still could not make an impression on Koblet's lead.

135 kilometers after he had made his attack Hugo Koblet entered the finish city of Agen. In the final kilometers of his great escape as he held off the entire peloton Koblet's face had shown no stress from the mighty effort. Before crossing the finish line Koblet took a sponge, wiped his face, and combed his hair. He had used the comb as a psychological weapon before. In the Tour of Switzerland he had combed his hair on the hardest climb to give the impression of ease. In reality he was suffering with hemorrhoids. But it fooled his rival, François Mahé, who gave up trying to stay with him.

|

||

Hugo Koblet during his epic stage 11 ride. |

||

Koblet then calmly got off his bike and started his stopwatch to see what advantage he gained over the rest of the field, a move that was not just for show. He had reason to distrust the timekeepers as his experience in stage 7 shows. He wanted no repeat of that mistake. 2 minutes and 35 seconds later the rest of the peloton finally crossed the line, exhausted and astonished by Koblet's great escape.

Without exception the peloton and press poured praise onto Koblet. "That was a performance without equal. If there were two Koblets in the sport I would retire from cycling tomorrow... If he climbs like he races on the flat, then we can say good-bye to the Yellow Jersey. None of us will wear it. If he doesn't have any problems, then we can all start looking for another job," said Raphaël Géminiani. It was after this stage that singer Jacques Grello coined the phrase "Pédaleur de Charme."

L'Equipe described the elite pack of riders chasing Koblet as "...skeptical and disconcerted at first, then utterly mortified and fiercely vindictive." There was another error in timing. This time it deprived Bauvin of his rightful evening in Yellow after Koblet's great ride.

The General Classification after stage 11:

- 1. Roger Levêque

- 2. Gilbert Bauvin @ 36 seconds

- 3. Hugo Koblet @ 3 minutes 27 seconds

Stage 12 was the start of another great Tour legend. On the last day before the Pyrenees, the Tour took another unexpected twist. A 10-man breakaway gained 18 minutes, 16 seconds on the peloton and Wim Van Est, "Iron William" as he was known to his fans, was in the Yellow Jersey.

Stage 13, from Dax to Tarbes, included both the Tourmalet and the Aubisque. Van Est, the first Dutchman to wear Yellow, was not going to give up the lead without a fight.

He turned pro in 1949 at the age of 26. In 1950 Van Est won Bordeaux–Paris. In 1951 he was selected for membership in the Dutch national Tour de France team. Van Est had grown up poor and had never traveled. This was the first time he had ever seen, much less ridden up a major climb. Knowing that he wasn't a climber, he went off early so that he could finish with the leaders and keep his Yellow Jersey. He had never done a mountain descent and did his best to follow the line of the experienced riders.

Close to catching Ockers and Coppi, he flatted near the top of the Aubisque. Remounting, he joined Magni and tried to hold his wheel on the descent. Van Est crashed, remounted, and continued down the mountain. The descent of the Aubisque is considered very difficult with its hairpin turns hidden behind sharp corners.

He went too fast into a decreasing radius turn and lost control of his bike. He flew off the side of the cliff and ended up 20 meters (70 feet) below. Trees broke his fall. He was able to grab one and by not moving much, fell no further.

|

||

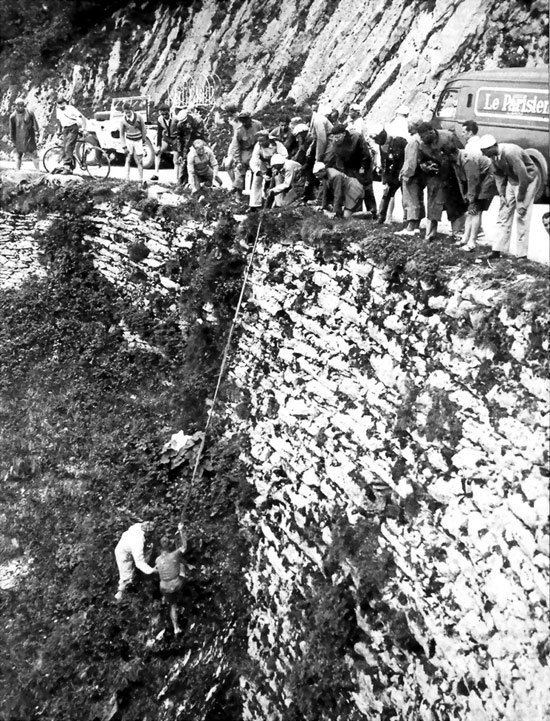

Van Est is pulled from the ravine. Photo courtesy Edwin Seldenthuis |

||

Looking way down below, people could barely see that he was waving his arms. He was alive! How to get him out? There were no ropes, but there were tubular tires.

The mechanics and riders got together, made a rope of linked tires, and sent someone down the sheer cliff to rescue Van Est. When he got back up to the road, his first question was about his bike. He wanted to resume racing. He was forced to get into the waiting ambulance and go to the hospital for an examination. This was a bitter pill for the man in Yellow. He was fine, just a few bruises and scratches. The entire Dutch team quit in solidarity.

Van Est went on to win more Tour stages and wore Yellow for a while in both the 1955 and the 1958 Tours.

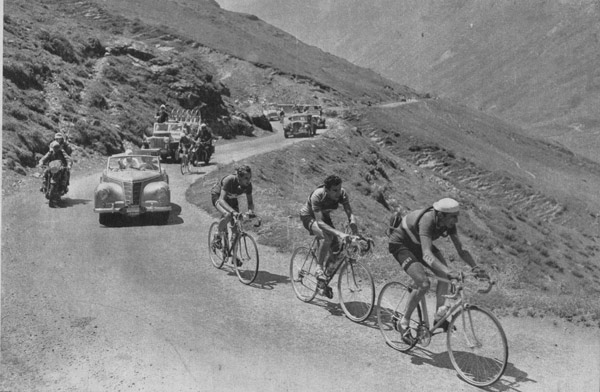

|

||

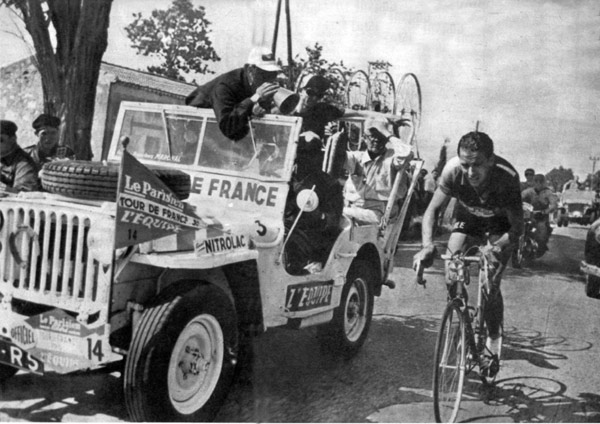

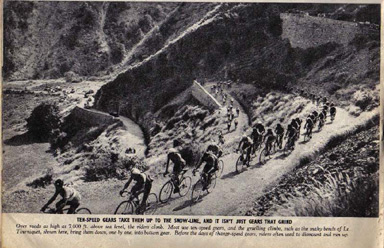

The Tour hits the Pyrenees. |

||

Meanwhile the race forged on. Raphaël Géminiani was the first man to go over the Aubisque and then got into the winning move of the day along with teammate Nello Lauredi, Serafino Biagioni of Italy and Gilbert Bauvin. Indeed, Géminiani was first to cross the line but was judged to have broken the rules and was relegated back to fourth place. The result was that Biagioni took the stage and Gilbert Bauvin was finally in Yellow. Koblet, Coppi, Ockers and Magni finished 9 minutes, 14 seconds back. Koblet was now down to fifth on General Classification, nearly 13 minutes behind the leader and over 6 minutes behind Géminiani.

Stage 14. Once again the dramatic backdrop of the Pyrenees served as a breathtaking stage for the Giants of the Road. The 142 kilometers between Tarbes and Luchon included the Tourmalet, Aspin and Peyresourde climbs. Coppi managed to forget his grief and display his awesome powers. He was the first man to cross the Aspin and Peyresourde while the field behind him was utterly shattered. Koblet punctured before the top of the Tourmalet, but calmly waited for service before chasing back his rivals. In a great chase back, Koblet eventually caught Coppi and outsprinted the Italian legend to take the stage and the Yellow Jersey.

|

||

Stage 14: Coppi leads Geminiani and Koblet on the Tourmalet. |

||

The General Classification now stood thus:

- 1. Hugo Koblet

- 2. Gilbert Bauvin @ 21 seconds

- 3. Raphaël Géminiani @ 32 seconds

- 4. Fausto Coppi @ 5 minutes 9 seconds

- 12. Louison Bobet @ 17 minutes 40 seconds

- 13. Stan Ockers @ 18 minutes 45 seconds

Stage 16 saw more drama on what was supposed to be a transitional stage. With the Alps yet to come, Koblet, Marinelli, Géminiani, Barbotin and Lazaridès attacked. Koblet won his third stage and only Géminiani at 1 minute, 32 seconds was still in contention for the Yellow Jersey. Coppi, overcome with the feelings of grief over his brother's recent death suffered a day of misery in the heat. He was dropped by the leading riders, eventually stopping and vomiting. Other accounts have attributed his problems to food poisoning. Bartali and Magni stayed with him to the finish line. Coppi ended up losing over 33 minutes, and was now out of the top 15 in the General Classification.

Stage 17, 224 kilometers between Montpellier and Avignon sent the Tour over Mont Ventoux for the first time in Tour history. On the climb 12 riders, all favorites, formed a leading break. By the time the group was halfway up the mountain only Raphaël Géminiani, Gino Bartali and Lucien Lazaridès were left at the front. Coppi and Magni were already 5 minutes in arrears. Koblet had suffered a derailleur problem and was limiting his losses riding in a high gear. Manager Bidot told Géminiani to slow the break because Bobet was closing in on them. With that help Bobet was able to bridge the gap. Pierre Barbotin made a tremendous effort to join the leading men, but with 2 kilometers to go Lazaridès (whose brother Apo was also riding in the race) attacked and was the first rider to cross the summit. Gino Bartali followed him. On the descent, Koblet caught up with the leading 5. In the closing kilometers Bobet attacked and won the stage by nearly a minute. That win galled Géminiani and from then on he raced not to beat Koblet but to be ahead of Bobet.

Over the next 2 stages Koblet maintained his 1 minute, 32 second advantage over Géminiani.

On Stage 20 Fausto Coppi gave another virtuoso performance. The Italian, now well out of overall contention, attacked early in the stage with Roger Buchonnet. He climbed the mighty Izoard and Vars alone. Koblet, seeing the danger of Coppi on a solo tear, responded and finished third that day. Raphaël Géminiani's challenge for the Yellow Jersey was over when he ended up over 7 minutes behind Koblet. The Swiss rider seemed destined to win the Tour on his first attempt.

Hugo Koblet must have relished Stage 22. It was the final Individual Time Trial, over 97 kilometers starting from Aix-les-Bains and finishing in Geneva, Switzerland. The "Pédaleur de Charme" was at his very best. Setting off at 2:32 p.m., Koblet started to reel in the riders who had already set off. He caught the great Gino Bartali who had started 8 minutes before him. As he passed Bartali, Koblet slowed and took his water bottle and placed it in the carrier of the struggling Italian. "Take it, Gino, there is still some left!" he said. In a previous race, Koblet had been dehydrated had asked Bartali for water. Gino had calmly had a drink and, then, looking at Koblet, emptied the remains of the bottle on the road.

At 5:11 PM Koblet entered the Frontenex Stadium in Geneva to immense cheers from the huge crowds. He had won the time trial by almost 5 minutes. He beat Coppi by 7½ minutes and Bobet by almost 13.

Koblet won the 1951 Tour by 22 minutes from Raphaël Géminiani. He never again reached such heady heights. It was a complete triumph for Koblet and his Swiss team. Second placed Raphaël Géminiani joked, "chasing after these white crosses [the Swiss National Jersey], you could end up finishing at the Red Cross!" Géminiani said that he was actually the winner. When he was asked about Koblet, he replied, "He doesn't count. I'm the first human." It has been speculated that had the French been more unified and worked harder to beat Koblet rather than each other, Géminiani might have won the Tour. I think that unlikely given the ease with which Koblet was able to handle his rivals no matter what the challenge.

|

||

Tour's end. Géminiani greets a fan. Koblet is with the sash to the right. |

||

1951 Tour de France final General Classification:

- 1. Hugo Koblet (Switzerland): 142 hours 20 minutes 14 seconds

- 2. Raphaël Géminiani (France) @ 22 minutes

- 3. Lucien Lazaridès (France) @ 24 minutes 16 seconds

- 4. Gino Bartali (Italy) @ 29 minutes 9 seconds

- 5. Stan Ockers (Belgium) @ 32 minutes 53 seconds

Climber's Competition:

- 1. Raphaël Géminiani: 66 points

- 2. Gino Bartali: 59 points

- 3. A three-way tie between Coppi, Koblet and Bernardo Ruiz at 41 points

Koblet reveled in his newfound fame and fortune. "Money used to slip through his fingers like water," said one teammate, "Hugo couldn't say no to anyone. Sponsors always wanted him for some occasion or party, journalists wanting this or that story, groups of pretty women permanently waiting for him at the finish line." His flamboyant lifestyle was hugely expensive and in complete contrast to his rival and compatriot Ferdy Kübler. With the glamour of a modern-day rock star, Koblet would arrive at races driving a Studebaker, while Ferdy would arrive by train, third class. "Ferdy looks after his money; if there were a fourth class, Ferdy would take it," commented Charly Gaul.

In a time of post-war economic growth, the big stars benefited from direct sponsorship—indeed, we'll see how Raphaël Géminiani did a great deal to open up sponsorship for riders. Pontiac Watches capitalized on Wim Van Est's tumble on the Aubisque and ran the ad, "His heart stopped but his Pontiac kept time." For all his Studebakers and elegance, Koblet was astonished when an Italian businessman greeted him after a race and presented him with a check for one million lire. The businessman had to explain that it was Koblet's commission from a company that had produced a "Koblet" comb.

But unlike the true greats, Koblet could not remain focused on his racing.

"This flamboyant behavior made him lazy in his training. I remember we planned a training ride on the Klausen Pass and said we would meet at his house at 7:30 a.m. He agreed. We showed up, buzzed the door...nothing. We buzzed for 7 minutes and finally he comes to the window, obviously still asleep! He lets us in and says he has to make some calls and we should go down to the coffee shop till he is ready. We go down there and now it's one hour later. He then comes up and says he forgot about some meeting he has to do but will be done by 10:00 o'clock. We said forget it and left without him. This happened so often we gave up riding with him. Yet in the mountains he could drop us all on the few kilometers he trained," commented teammate Gottfried Weilenmann.

Following the Tour, Koblet accepted an offer to ride the Tour of Mexico. Exotic Central America fascinated him, and it suited his sense of adventure. Koblet was greeted by the President of Mexico and enjoyed the hospitality and the parties. One episode demonstrates his prodigious talent. Koblet had hardly ridden for a month and had been partying non-stop. On a mountainous stage in the Sierra Madre he left half an hour before the Mexican amateurs for a 200 kilometer solo race. The heat was intense and the Mexicans were enthusiastic about trying to catch the Tour de France winner. Nevertheless Koblet crossed the line 30 minutes, 35 seconds ahead of the chasing peloton.

While in Mexico, he contracted an illness that caused him kidney and lung problems that would plague him for the rest of his life. Koblet was never quite the same cyclist again.

A crash on the descent of the Aubisque in the Tour de France in 1953 caused Koblet more health problems and from then on his career went into a slow decline. While track racing with old friend Fausto Coppi in Colombia in 1957 the idea of emigrating to Argentina with thoughts of car franchises and other schemes was discussed (Coppi was trying to establish his bike frame business there). In 1958 Koblet hung the bike on the nail and moved to Argentina in search of fortune. He became homesick and returned to Europe but found it difficult to settle. His wife and great love, the model Sonja Bühl, had divorced him and his good looks were starting to fade.

On November 6, 1964, witnesses saw a white Alfa Romeo speeding along the road to Esslingen at about 140 kilometers an hour. The weather was perfect, the road was good but the car plowed straight into a tree. Koblet had been alone in the car. Doctors operated on him for 4 hours. Koblet was only 39 when he died. By a bizarre twist of fate, the doctor who was first at the scene and later confirmed his death was named Kübler. To this day it is debated whether or not Koblet had committed suicide.

Years later when the 80-year-old Ferdy Kübler was asked about Koblet, the old man was nearly moved to tears as he remembered his friend and rival. The old man's reply was simple: "How lucky I was to have ridden with a great champion like Koblet."

.