1994 Giro d'Italia

77th edition: May 22- June 12

Results, stages with running GC, map, photos and history

1993 Giro | 1995 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1994 Giro Quick Facts | 1994 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1994 Giro d'Italia

A special merci beaucoup (thank you very much) to Yves Guilleux for supplying GC standings down to 10th place for each stage.

Map of the 1994 Giro d'Italia

3,721 km raced at an average speed of 37.15 km/hr

153 starters and 99 classified finishers

Miguel Indurain was the favorite, but he came to the Giro undertrained was soundly beaten by Evgeni Berzin, who was in the form of his life.

Young Marco Pantani's incredible climbing prowess was on full display when he won back-to-back stages and finishing second to Berzin, ahead of Indurain.

Indurain did deliver a spectacular ride that summer in the Tour, his climbing better than at any point in his career.

James Witherell's book Bicycle History is available in both print and eBook versions. Just click on the Amazon link above right to learn more.

1994 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 100hr 21min 21sec

Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 100hr 21min 21sec- Marco Pantani (Carrera) @ 2min 51sec

- Miguel Indurain (Banesto) @ 3min 23sec

- Pavel Tonkov (Lampre) @ 11min 16sec

- Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera) @ 11min 58sec

- Nelson Rodriguez (ZG Mobili) @ 13min 17sec

- Massimo Podenzana (Navigare-Blue Storm) @ 14min 35sec

- Gianni Bugno (Polti) @ 15min 26sec

- Armand de las Cuevas (Castorama) @ 15min 35sec

- Andrew Hampsten (Motorola) @ 17min 21sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov (Carrera) @ 18min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli (Lampre) @ 19min 36sec

- Georg Totschnig (Polti) @ 20min 4sec

- Moreno Argentin (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 27min 47sec

- Pascal Richard (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 28min 38sec

- Ivan Gotti (Polti) @ 28min 59sec

- Flavio Giupponi (Brescialat-Refin) @ 29min 39sec

- Udo Bölts (Telekom) @ 30min 23sec

- Roberto Conti (Lampre) @ 33min 41sec

- Davide Rebellin (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 34min 48sec

- Serguei Outschakov (Polti) @ 37min 41sec

- Francesco Casagrande (Mercatone Uno) @ 45min 32sec

- Franco Vona (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 45min 38sec

- Piotr Ugrumov (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 49min 26sec

- Oscar Pellicioli (Polti) @ 52min 13sec

- Enrico Zaina (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 52min 32sec

- Laurent Madouas (Castorama) @ 59min 19sec

- Andrea Ferrigato (ZG Molbili) @ 1hr 3min 26sec

- Michele Coppolillo (Navigare-Blue Storm) @ 1hr 6min 35sec

- Rolf Sørensen (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 1hr 8min 17sec

- Gianni Faresin (Lampre) @ 1hr 11min 12sec

- Giuseppe Guerini (Navigare-Blue Storm) @ 1hr 11min 27sec

- Federico Muñoz (Kelme) @ 1hr 12min 44sec

- Gérard Rué (Banesto) @ 1hr 14min 25sec

- Alberto Volpi (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 1hr 17min 4sec

- Bruno Cenghialta (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 1hr 19min 42sec

- Rodolfo Massi (Amore & Vita-Galatron) @ 1hr 20min 59sec

- Augusto Triana (Kelme) @ 1hr 21min 2sec

- Alvaro Mejia (Motorola) @ 1hr 25min 8sec

- Thomas Davy (Castorama) @ 1hr 25min 8sec

- Massimo Ghirotto (ZG Mobili) @ 1hr 27min 43sec

- Jean-Cyril Robin (Castorama) @ 1hr 32min 13sec

- Michele Bartoli (Mercatoe Uno) @ 1hr 33min 11sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov (Polti) @ 1hr 33min 40sec

- Andrea Chiurato (Mapei-Clas) @ 1hr 34min 55sec

- Franco Chioccioli (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 42min 2sec

- Bruno Leali (Brescialat-Refin) @ 1hr 42min 26sec

- Stefano Zanini (Navigare-Blue Storm) @ 1hr 53min 3sec

- José Luis Arrieta (Banesto) @ 2hr 0min 41sec

- Produenci Indurain (Banesto) @ 2hr 2min 33sec

- Gianluca Bortolami (Mapei-Clas) @ 2hr 3min 31sec

- José Ramon Uriarte (Banesto) @ 2hr 5min 7sec

- Mauro-Antonio Santaromita (ZG Mobili) @ 2hr 5min 9sec

- Julio Cesar Ortegon (Kelme) @ 2hr 6min 42sec

- Laurent Brochard (Castorama) @ 2hr 8min 52sec

- Fabio Roscioli (Brescialat-Refin) @ 2hr 12min 37sec

- Giancarlo Perini (ZG Mobili) @ 2hr 15min 20sec

- Jens Heppner (Telekom) @ 2hr 15min 43sec

- Mario Chiesa (Carrera) @ 2hr 17min 19sec

- Flavio Vanzella (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 2hr 18min 16sec

- Paolo Fornaciari (Mercatone Uno) @ 2hr 19min 35sec

- Felice Puttini (Brescialat-Refin) @ 2hr 20min 51sec

- Leonardo Sierra (Carrera) @ 2hr 24min 2sec

- Marco Saligari (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 2hr 24min 57sec

- Stéphane Heulot (Banesto) @ 2hr 27min 18sec

- Zbigniew Spruch (Lampre) @ 2hr 30min 14sec

- Santiago Crespo (Banesto) @ 2hr 30min 27sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli (ZG Mobili) @ 2hr 32min 4sec

- Guido Bontempi (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 2hr 35min 21sec

- Bjarne Riis (Gewiss-Ballan) @ 2hr 36min 38sec

- Nestor Mora (Kelme) @ 2hr 38min 45sec

- Libardo Niño (Kelme) @ 2hr 39min 50sec

- Andrei Syptytkowski (Kelme) @ 2hr 43min 58sec

- Giovanni Fidanza (Polti) @ 2hr 46min 50sec

- Maurizio Molinari (Amore & Vita-Galatron) @ 2hr 47min 37sec

- Stefano Checchin (Carrera) @ 2hr 47 38sec

- Riccardo Forconi (Amore & Vita-Galatron) @ 2hr 47min 53sec

- Andrei Teteriouk (Mapei-Clas) @ 2hr 49min 31sec

- Giuseppe Calcaterra (Amore & Vita-Galatron) @ 2hr 51min 24sec

- Davide Bramati (Lampre) @ 2hr 51min 26sec

- Michel Dernies (Motorola) @ 2hr 55min 21sec

- Gianluca Gorini (Jolly Componibili-Cage 94) @ 2hr 55min 34sec

- Dario Nicoletti (Mapei-Clas) @ 2hr 58min 47sec

- Steve Larsen (Motorola) @ 3hr 0min 48sec

- Mario Scirea (Polti) @ 3hr 1min 44sec

- Luca Scinto (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 3hr 2min 41sec

- Erwin Nijboer (Banesto) @ 3hr 2min 47sec

- Laurent Pillon (Jolly Componibili-Cage 94) @ 3hr 4min 36sec

- Mariano Piccoli (Mercatone Uno) @ 3hr 7min 32sec

- Fausto Dotti (Jolly Componibili-Cage 94) @ 3hr 12min 36sec

- Giovanni Lombardi (Lampre) @ 3hr 15min 41sec

- Valerio Tebaldi (Mapei-Clas) @ 3hr 16min 43sec

- Dominik Krieger (Telekom) @ 3hr 16min 58sec

- René Foucachon (Jolly Componibili-Cage 94) @ 3hr 21min 9sec

- Brian Smith (Motorola) @ 3hr 22min 35sec

- Simone Borgheresi (Amore & Vita-Galatron) @ 3hr 22min 42sec

- Roberto Pagnin (Navigare-Blue storm) @ 3hr 31min 38sec

- Eros Poli (Mercatone Uno) @ 3hr 34min 4sec

- Jürgen Werner (Telekom) @ 3hr 35min 5sec

Points Classification:

Djamolidine Abdoujaprov (Polti): 202 points

Djamolidine Abdoujaprov (Polti): 202 points- Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 182

- Gianni Bugno (Polti): 148

- Miguel Indurain (Banesto), Stefano Zanini (Navigare-Blue Storm): 132

Climbers' Competition:

Pascal Richard (GB-MG-Technogym): 78 points

Pascal Richard (GB-MG-Technogym): 78 points- Michele Coppolillo (Navigare-Blue Storm): 58

- Marco Pantani (Carrera): 44

- Nelson Rodriguez (ZG Mobili): 24

- Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 20

Young Rider:

Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan) 100hr 41min 21sec

Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan) 100hr 41min 21sec- Marco Pantani (Carrera) @ 2min 51sec

- Wladimir Belli (Lampre) @ 19min 36sec

- Georg Totschnig (Polti) @ 20min 4sec

- Pascal Richard (GB-MG-Technogym) @ 34min 46sec

Intergiro:

Djamolidine Abdoujaparov: 62hr 0min 39sec

Djamolidine Abdoujaparov: 62hr 0min 39sec- Evgeni Berzin @ 44sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli (ZG Mobili) @ 1min 50sec

- Stefano Zanini (Navigare-Blue Storm)

- Armand de las Cuevas (Castorama)

Team Classification:

- Carrera: 302hr 25min 45sec

- Polti @ 24min 55sec

- Lampre @ 24min 56sec

- Gewiss-Ballan @ 36min21sec

- GB-MG-Technogym @ 41min 23sec

1994 Giro stage results with running GC:

Sunday, May 22: Stage 1A, Bologna - Bologna, 86 km

- Endrio Leoni: 2hr 0min 10sec

- Giovanni Lombardi s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Samuele Schiavina s.t.

- Giovanni Fidanza s.t.

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Uwe Raab s.t.

- Jürgen Werner s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

GC after Stage 1A:

- Endrio Leoni: 1hr 59min 58sec

- Adriano Baffi @ 2sec

- Giovanni Lombardi @ 4sec

- Jan Svorada @ 8sec

- Dimitri Konyshev @ 10sec

- Fabio Baldato @ 12sec

- Samuele Schiavina s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Uwe Raab s.t.

Sunday, May 22: Stage 1B, Bologna 7 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Armand de las Cuevas: 7min 52sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 2sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 5sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 12sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 14sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 17sec

- Rolf Sørensen @ 21sec

- Thierry Marie @ 22sec

- Andrea Chiurato @ 23sec

- Massimiliano Lelli s.t.

GC after Stage 1B:

- Armand de las Cuevas: 2hr 8min 13sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 2sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 5sec

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Francesco Casagrande @ 12sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 14sec

- Maximilian Sciandri @ 16sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 17sec

- Endrio Leoni @ 20sec

- Rolf Sørensen @ 21sec

Monday, May 23: Stage 2, Bologna - Osimo, 232 km

![]() Major ascents: Agugliano, Offagna

Major ascents: Agugliano, Offagna

- Moreno Argentin: 6hr 13min 31sec

- Andrea Ferrigato @ 6sec

- Davide Rebellin @ 8sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 12sec

- Pascal Richard s.t.

- Giorgio Furlan s.t.

- Stefano Della Santa s.t.

- Evgeni Berzin s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

- Marco Pantani s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

Note - This is the GC after correcting mistakes that were confessed the next day. There was a mistake for 39 riders, among them Indurain, De Las Cuevas and Chiappucci (the latter one being out of the top 10). The newspapers indicated De Las Cuevas at 16 sec, Indurain at 21 sec, i.e. a mistake of 6 seconds. The mistake for Chiappucci was 3 seconds

- Moreno Argentin: 8hr 21mn 49sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 9sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 10sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 15sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 19sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 21sec

- Andrea Ferrigato @ 32sec

- Pascal Richard @ 40sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 41sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 42sec

Tuesday, May 24: Stage 3, Osimo - Loreto Aprutino, 185 km

![]() Major ascents: Collecorvino, Loreto Aprutino

Major ascents: Collecorvino, Loreto Aprutino

- Gianni Bugno: 4hr 25min 20sec

- Stefano Zanini @ 2sec

- Davide Rebellin s.t.

- Francesco Casagrande s.t.

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

- Evgeni Berzin s.t.

- Armand de las Cuevas s.t.

- Claudio Chiappucci s.t.

- Stefano Della Santa s.t.

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Moreno Argentin: 12hr 47min 11sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 7sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 9sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 10sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 15sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 19sec

- Andrea Ferrigato @ 32sec

- Stefano Zanini @ 34sec

- Pascal Richard @ 40sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 41sec

Wednesday, May 25: Stage 4, Montesilvano Marina - Campitello Matese, 204 km

![]() Major ascents: Valico Tre Termini, Campitello Matse

Major ascents: Valico Tre Termini, Campitello Matse

- Evgeni Berzin: 5hr 33min 37sec

- Oscar Pellicioli s.t.

- Waldimir Belli @ 17sec

- Davide Rebellin @ 47sec

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Stefano Della Santa s.t.

- Marco Giovannetti s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

- Armand de las Cuevas s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Evgeni Berzin: 18hr 20min 45sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 57sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 58sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 1min 0sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 1min 5sec

- Oscar Pellicioli @ 1min 8sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 1min 31sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 1min 32sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 33sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 43sec

Thursday, May 26: Stage 5, Campbasso - Melfi, 153 km

![]() Major ascent: Crocella di Motta

Major ascent: Crocella di Motta

- Endrio Leoni: 3hr 41min 39sec

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Giovanni Lombardi s.t.

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

- Massimo Strazzer s.t.

- Uwe Raab s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Samuele Schiavina s.t.

- Maximilian Sciandri s.t.

GC after stage 5:

- Evgeni Berzin: 22hr 2min 24sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 57sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 1min 0sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 1min 5sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 1min 26sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 1min 31sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 1min 32sec

- Oscar Pellicioli @ 1min 36sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 43sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 53sec

Friday, May 27: Stage 6, Potenza - Caserta, 215 km

![]() Major ascents: Valico di Ponte Tifisciullo, Passo Crucci, Summonte

Major ascents: Valico di Ponte Tifisciullo, Passo Crucci, Summonte

- Marco Saligari: 5hr 39min 38sec

- Massimo Ghirotto s.t.

- Heinz Imboden s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Gianni Faresin s.t.

- Gianluca Pierobon @ 3min 1sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov s.t.

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Jan Svorada s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Evgeni Berzin: 27hr 45min 3sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 57sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 1min 0sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 1min 5sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 1min 26sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 1min 31sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 1min 32sec

- Oscar Pellicioli @ 1min 36sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 43sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 53sec

Saturday, May 28: Stage 7, Fiuggi - Fiuggi, 119 km

![]() Major ascents: Salita della Rosina x 2

Major ascents: Salita della Rosina x 2

- Laudelino Cubino: 2hr 56min 12sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1sec

- Fabian Jeker s.t.

- Fabio Bordonali s.t.

- Oscar Pellicioli s.t.

- Andrea Chiurato s.t.

- Michele Bartoli @ 10sec

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Alessio di Basco s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

GC after stage 7:

- Evgeni Berzin: 30hr 41min 25sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 57sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 1min 0sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 1min 5sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 1min 26sec

- Oscar Pellicioli @ 1min 27sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 1min 31sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 1min 32sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 43sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 53sec

Sunday, May 29: Stage 8, Grossetto - Follonica 44 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Evgeni Berzin: 50min 46sec. 52.00 km/hr

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 1min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 1min 41sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 2min 34sec

- Massimiliano Lelli @ 2min 39sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 2min 48sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 2min 49sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 2min 55sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 3min 11sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 3min 19sec

- Andrea Chiurato s.t.

- Flavio Vanzella @ 3min 38sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 3min 49sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 3min 50sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 3mn 58sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov @ 4min 3sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 4min 8sec

- Jan Svorada @ 4min 16sec

- Thierry Marie @ 4min 19sec

- Walter Bonca @ 4min 20sec

GC after Stage 8:

- Evgeni Berzin: 31hr 32min 11sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 38sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 20sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 6min 19sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

Monday, May 30: Stage 9, Castiglione dell Pescaia - Pontedera, 153 km

- Jan Svorada: 3hr 25min 7sec

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Giovanni Fidanza s.t.

- Jan Schur s.t.

- Uwe Raab s.t.

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Maximilian Sciandri s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Evgeni Berzin: 34hr 57min 18sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 38sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 20sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Stefano Della Santa @ 6min 19sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

Tuesday, May 31: Stage 10, Marostica - Marostica, 115 km

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov: 2hr 33min 7sec

- Giovanni Lombardi s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Roberto Pagnin s.t.

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Mario Chiesa s.t.

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

- Fabio Bordonali s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Evgeni Berzin: 37hr 30min 31sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 32sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 58sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 6min 42sec

Wednesday, June 1: Stage 11, Marostica - Bibione, 165 km

- Jan Svorada: 4hr 8min 5sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov s.t.

- Uwe Raab s.t.

- Maximilian Sciandri s.t.

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Giovanni Fidanza s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Roberto Pelliconi s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Evgeni Berzin: 41hr 38min 36sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 32sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 58sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 6min 42sec

Thursday, June 2: Stage 12, Bibione - Kranj (Slovenia), 204 km

![]() Major ascent: Valico di Črni Vrh

Major ascent: Valico di Črni Vrh

- Andrea Ferrigato: 4hr 47min 4sec

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov @ 2sec

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Fabio Bordonali s.t.

- Jens Heppner s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Francesco Casagrande s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Evgeni Berzin: 46hr 25min 42sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 32sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 58sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 6min 42sec

Friday, June 3: Stage 13, Kranj (Slovenia) - Lienz (Austria), 243 km

![]() Major ascents: Gailberg Sattel, Bannberg

Major ascents: Gailberg Sattel, Bannberg

- Michele Bartoli: 5hr 56min 49sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli @ 2min 31sec

- Flavio Vanzella @ 2min 59sec

- Laurent Madouas s.t.

- Thomas Davy @ 3min 6sec

- Mario Chiesa @ 3min 49sec

- Alberto Volpi @ 3min 59sec

- Paolo Fornaciari @ 6min 45sec

- Nestor Mora s.t.

- Riccardo Forconi @ 8min 59sec

GC after stage 13:

- Evgeni Berzin: 52hr 36min 1sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 32sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Marco Giovanetti @ 4min 58sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 5min 2sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

- Marco Pantani @ 6min 28sec

Saturday, June 4: Stage 14, Lienz (Austria) - Merano, 235 km

![]() Major ascents: Passo di Stalle, Passo di Furcia, Passo delle Erbe, Passo di Eores, Passo di Monte Giovo

Major ascents: Passo di Stalle, Passo di Furcia, Passo delle Erbe, Passo di Eores, Passo di Monte Giovo

- Marco Pantani: 7hr 34min 4sec. 30.45 km/hr

- Gianni Bugno @ 40sec

- Claudio Chiappucci s.t.

- Davide Rebellin s.t.

- Evgeni Berzin s.t.

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

- Massimo Podenzana s.t.

- Flavio Giupponi s. t.

- Serguei Outschakov s.t.

- Nelson Rodriguez s.t.

GC after stage 14:

- Evgeni Berzin: 60hr 19min 45sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 16sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 2min 24sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 39sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 24sec

- Marco Pantani @ 5min 36sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 6min 9sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 6min 25sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 6min 42sec

- Davide Rebellin @ 8min 38sec

Sunday, June 5: Stage 15, Merano - Aprica, 188 km

![]() Major ascents: Passo dello Stelvio, Passo del Mortirolo, Valico di Santa Cristina

Major ascents: Passo dello Stelvio, Passo del Mortirolo, Valico di Santa Cristina

- Marco Pantani: 6hr 55min 58sec. 27.12 km/hr

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 2min 52sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 3min 27sec

- Nelson Rodriguez s.t.

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 30sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 4min 6sec

- Udo Bölts s.t.

- Gianni Bugno @ 5min 50sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Laudelino Cubino s.t.

- Flavio Giupponi @ 6min 59sec

- Roberto Conti s.t.

- Andrew Hampsten @ 7min 2sec

- Armand de las Cuevas s.t.

- Pascal Richard @ 7min 51sec

- Enrico Zaina @ 8min 7sec

- Georg Totschnig @ 10min 3sec

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Andrea Chiurato @ 11min 24sec

GC after Stage 15:

- Evgeni Berzin: 67hr 19min 49sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 18sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 3sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 4min 8sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 4min 41sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 5min 12sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 7min 53sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 9min 13sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 10min 15sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 11min 48sec

Monday, June 6: Stage 16, Sondrio - Stradella, 220 km

![]() Major ascent: Canneto Pavese

Major ascent: Canneto Pavese

- Maximilian Sciandri: 6hr 24min 36sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Enrico Zaina s.t.

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov s.t.

- Stefano Zanini s.t.

- Giovanni Lombardi s.t.

- Gianluca Bortolami s.t.

- Massimo Ghirotto s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Evgeni Berzin: 73hr 44min 26sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 18sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 3sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 4min 8sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 4min 41sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 5min 12sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 7min 53sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 9min 13sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 10min 15sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 12min 0sec

Tuesday, June 7: Stage 17, Santa Maria della Versa - Lavagna, 200 km

![]() Major ascents: Montù Beccaria, Passo di Tomario, Passo di Cento Croci

Major ascents: Montù Beccaria, Passo di Tomario, Passo di Cento Croci

- Jan Svorada: 5hr 26min 4sec

- Giovanni Lombardi @ 2sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov s.t.

- Roberto Pagnin s.t.

- Giancarlo Perini s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch @ 56sec

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Fabio Roscioli s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Evgeni Berzin: 79hr 11min 26sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 18sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 3sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 4min 8sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 4min 41sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 5min 12sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 7min 53sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 9min 13sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 10min 15sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 12min 0sec

Wednesday, June 8: Stage 18, Chiavari - Passo del Bocco 35 km individual time trial (cronometro)

![]() Major ascent: Passo del Ghiffi

Major ascent: Passo del Ghiffi

- Evgeni Berzin: 59min 52sec. 35.078 km/hr

- Miguel Indurain @ 20sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 37sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 2min 4sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 2min 11sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 2min 39sec

- Georg Totschnig @ 2min 59sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 3min 7sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 3min 10sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 3min 21sec

- Francesco Casagrande @ 3min 49sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 3min 53sec

- Gianni Faresin @ 4min 2sec

- Laudelino Cubino @ 4min 14sec

- Davide Rebellin @ 4min 15sec

- Pascal Richard @ 4min 23sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 4min 31sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 4min 34sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 4min 42sec

- Rodolfo Massi @ 4min 50sec

GC after Stage 18:

- Evgeni Berzin: 80hr 11min 13sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 51sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 23sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 7min 15sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 7min 16sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 9min 12sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 11min 3sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 11min 52sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 15min 26sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 15min 53sec

Thursday, June 9: Stage 19, Lavagna - Bra, 212 km

![]() Major ascent: Passo di Scoffera

Major ascent: Passo di Scoffera

- Massimo Ghirotto: 5hr 26min 50sec

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Massimo Podenzana s.t.

- Rodolfo Massi s.t.

- Paolo Fornaciari @ 2min 17sec

- Fabio Bordonali s.t.

- Maurizio Molinari s.t.

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Fabio Roscioli s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Evgeni Berzin: 85hr 40min 29sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 51sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 23sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 7min 15sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 7min 16sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 9min 12sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 11min 3sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 11min 52sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 15min 26sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 15min 53sec

Friday, June 10: Stage 20, Cuneo - Les Deux Alpes, 206 km

![]() Major ascents: Colle dell'Agnello, Col d'Izoard, Col du Lautaret, les Deux Alpes

Major ascents: Colle dell'Agnello, Col d'Izoard, Col du Lautaret, les Deux Alpes

- Vladimir Poulnikov: 6hr 28min 50sec. 31.016 km/hr

- Nelson Rodriguez s.t.

- Roberto Conti @ 14sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 21sec

- Georg Totschnig @ 30sec

- Hernan Buenahora @ 1min 51sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 55sec

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

- Evgeni Bezin s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 2min 10sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 2min 38sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 3min 15sec

- Alvaro Majia @ 5min 3sec

- Franco Vona @ 5min 51sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 8min 22sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 9min 27sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov @ 9min 29sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 10min 8sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 10min 33sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Evgeni Berzin: 92hr 11min 14sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 51sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 23sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 11min 16sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 12min 7sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 13min 23sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 14min 35sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 14min 48sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 15min 28sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 16min 36sec

Saturday, June 11: Stage 21, Les Deux Alpes - Sestriere, 121 km

![]() Major ascents: Col du Lautaret, Col de Montgenèvre, Sestriere x 2

Major ascents: Col du Lautaret, Col de Montgenèvre, Sestriere x 2

- Pascal Richard: 3hr 30min 53sec. 34.427 km/hr

- Gérard Rué @ 1min 0sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 31sec

- Laurent Madouas @ 2min 46sec

- Andrea Chiurato @ 3min 36sec

- Rolf Sørensen @ 4min 27sec

- Claudio Chiappucci s.t.

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 4min 30sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 4min 34sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 4min 36sec

- Giuseppe Guerini st.

- Vladimir Poulnikov s.t.

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Miguel Indurain s.t.

- Evgeni Berzin s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Georg Totschnig s.t.

- Roberto Conti s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Evgeni Berzin: 95hr 46min 43sec

- Marco Pantani @ 2min 51sec

- Miguel Indurain @ 3min 23sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 11min 16sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 11min 58sec

- Nelson Rodriguez @ 13min 17sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 14min 35sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 15min 26sec

- Armand de las Cuevas @ 15min 35sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 17min 21sec

Sunday, June 12: 22nd and Final Stage, Torino - Milano, 198 km

- Stefano Zanini: 4hr 54min 38sec

- Djamolidine Abdoujaparov s.t.

- Roberto Pagnn s.t.

- Giovanni Lombardi s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Gialuca Gorini s.t.

- Gianluca Bortolami s.t.

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Andrei Teteriuk s.t.

- Claudio Chiappucci s.t.

The Story of the 1994 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Induráin came to the Giro with only twenty days of racing in his legs and no significant results. During the 1993 Tour he started to run out of gas as Tony Rominger cudgeled him day after day. The Swiss rider thought that if he hadn’t given up time early in the Tour, Induráin wouldn’t have had an early lead that allowed him to ride conservatively and negatively. Instead, he would have been forced to go on the offensive and that extra expenditure of energy might have cost him dearly and put the race in play. We’ll never know. But it certainly looked like Induráin was taking the early 1994 season rather easy and was not going to repeat 1993 and get over-cooked attempting the Giro/Tour double.

Bugno had won nothing of note in 1993, but in the spring of 1994 he won one of the most prestigious of the Classics, the Tour of Flanders.

The Carrera team was always a problem for Induráin and this year he had to have an extra set of eyes. Not only did he have to worry about Claudio Chiappucci’s constant and unexpected attacks, Carrera also had brilliant young climber Marco Pantani to torment the Spaniard.

As a teenager, Marco Pantani’s climbing ability was already striking. Like Coppi, his parents were too poor to buy him a racing bike. But Italy is covered with a complex web of clubs and sponsors that help promising young riders get equipment and coaching, and this was true in Pantani’s case when he joined the Fausto Coppi Sports Club. As he moved up the ranks of amateur racing, he made three attempts to win the Baby Giro. A fall ruined his first chance, but he still took third place. Inattention at a crucial moment in his second attempt led him to miss an important break, resulting in second place. But in 1992 he cemented his victory in the Girobio with a tour de force ride over three of the famous climbs that surround the Gruppo Sella massif: the Sella, Gardena and Campolongo passes.

That August he signed a professional contract to race for Davide Boifava’s Carrera team. Boifava had been in contact with Pantani for a while, watching him since 1990. Full of confidence, Pantani demanded bonus clauses in his pro contract for winning the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France.

He may have felt sure of his cycling abilities, but during his short life he had already displayed some of the personality problems that would later spell so much trouble: a sense of insecurity that his Danish girlfriend would later say was rooted in a deep inferiority complex, as well as difficulty communicating and bonding in a normal way with friends, acquaintances and workmates.

From the last part of the 1992 season through the spring of 1993, Carrera raced Pantani hard, using him in short stage races as well as sending him to northern Europe for some of the Classics. He handled this trial by fire well, finishing nearly all of his races, and he showed the right stuff with a fifth in the Giro del Trentino. Then, insanely, Carrera tossed him into the Giro to help Chiappucci. It was all too much too soon and as we’ve seen, Pantani had to retire during stage eighteen with tendinitis, marking the end his 1993 season.

Gewiss had a formidable team. They were winning everything and the Giro was in their sights with Moreno Argentin, Piotr Ugrumov and the brilliant young Russian Evgeni Berzin, who had already won Liège–Bastogne–Liège that spring.

The Giro started with a split-stage day. In the morning the course was a loop out and back to Bologna. Endrio Leoni won the sprint, which was so fast the peloton splintered in the final kilometer.

More important was the afternoon seven-kilometer pan-flat individual time trial. Winner of the stage was a time trial specialist, Armand de las Cuevas. Berzin was second, only 2 seconds slower and Induráin was third at 5 seconds, while Bugno lost 14 seconds. De las Cuevas was the new leader with Berzin second and Induráin third.

During stage two the Giro traveled south along the Adriatic coast for an uphill grunt into the city of Osimo. Ugrumov took a flyer and was looking like a winner, but just as he started to fade, Argentin launched an attack that was nothing short of astonishing. He flew by his teammate and continued to distance himself from the field all the way to the line. Argentin was the year’s third owner of the Pink Jersey.

Several times during the rolling stage three Bugno blasted away from the pack and was brought back. In the closing kilometers, with their steady climb into Loreto Aprutino, he escaped and managed to come across the line two seconds in front of the peloton. Good, but not good enough for pink. Argentin still held the lead with Bugno second at 7 seconds and Berzin third at 9.

The first of four hilltop finishes came in stage four in the south of Italy. The riders left the flat road after about 60 kilometers and spent the next 140 in the mountains to finish at Campitello Matese.

Oscar Pelliccioli went hunting for a stage win as the final hill began to rise. Others tried to get away, but when Berzin exploded out of what was left of the peloton it was over for everyone else. Beautiful is the only word for his form as he appeared to effortlessly stroke the pedals. He caught Pelliccioli near the top and out-sprinted him for the stage. Wladimir Belli was the first chaser across the line, coming in third; 47 seconds after Berzin was Marco Pantani. Argentin lost three minutes on the climb.

The General Classification stood thus:

1. Evgeni Berzin

2. Gianni Bugno @ 57 seconds

3. Wladimir Belli @ 58 seconds

The race headed north, up the Tyrrhenian side of the boot, without any particular effect upon the standings. Stage eight was a 44-kilometer individual time trial ending in the Tuscan town of Follonica. I don’t think anyone could have predicted the outcome of this stage. Berzin destroyed the field. Induráin, unable to find his rhythm, could only manage fourth.

Evgeni Berzin winning the stage eight time trial in Follonica

The stage results:

1. Evgeni Berzin

2. Armand de las Cuevas @ 1 minute 16 seconds

3. Gianni Bugno @ 1 minute 41 seconds

4. Miguel Induráin @ 2 minutes 34 seconds

5. Massimiliano Lelli @ 2 minutes 39 seconds

That yielded the following General Classification:

1. Evgeni Berzin

2. Armand de las Cuevas @ 2 minutes 16 seconds

3. Gianni Bugno @ 2 minutes 38 seconds

4. Miguel Induráin @ 3 minutes 39 seconds

5. Marco Giovannetti @ 4 minutes 20 seconds

A knife had been driven into the heart of the Induráin race strategy: gain significant time in the time trials and then match the climbers in the mountains. It was a coolly economic method, but one had to win the time trials to make it work. Induráin was aware of the danger of his situation and began scrapping for sprint time bonuses.

Bugno was riding as if he had limitless reserves. Strangely for a former Giro winner and a rider sitting in third, he assumed gregario duties for his Polti team, chasing down breaks and setting up sprints for Polti’s speedster, Djamolidine Abdoujaparov. From the start of this year’s Giro he had been careless about losing or gaining time. When he won stage three Bugno slowed well before the line, being vastly more interested in making sure he could do a two-arm crowd salute than in squeezing every possible second out of his break.

The Giro went into Austria and in stage fourteen, headed through the Dolomites to Merano, crossing four major passes on the way. It was on the final pass, the Giovo, that the real action occurred. A break had been away for many kilometers and on the Giovo it started to rain. Pascal Richard left the break as it began to disintegrate. Back in the maglia rosa group, Marco Pantani was finally given his freedom to seek a stage win, because his director knew that Chiappucci, also off the front, was not going to bring home the bacon in the 1994 Giro.

Pantani, then sitting in tenth place at 6 minutes 28 seconds, blasted off, catching and passing all of the breakaway riders but Richard, and on the dangerous wet descent, caught and passed him. Tiny Pantani was a fearsome descender, one of the best of his era. Bugno put his team to work chasing Pantani, who still had nearly 30 kilometers of solo riding to go. Pantani had no intention of letting the moment go to waste and took every chance, cutting every corner to stay ahead of his pursuers.

Pantani won the stage, 40 seconds ahead of the maglia rosa group led in by Bugno and Chiappucci. This perfectly executed ride was Pantani’s first professional victory, moving him up to sixth place. That evening, hungry for more, Pantani badgered his director for more information about the next day’s climbs.

That following day was harder still, with the north face of the Stelvio, the Mortirolo and the Santa Cristina. It was snowing at the top of the Stelvio and there was some discussion of cancelling the climb, but the organizers decided to take the chance. The riders went up between walls of snow lining the wet, sloppy road of the Stelvio. Franco Vona was first over, while the Classification men stayed together.

On the Mortirolo a small group of Berzin, Pantani and de las Cuevas formed behind Vona and a few other adventurers. And then Pantani was gone. Berzin tried to stay with him but soon realized the folly of his move.

Pantani flew by all the breakaway riders who had been in front of him and crested the Mortirolo alone. Further back, Induráin dropped the others including Berzin and went off in search of Pantani. At the bottom of the Mortirolo, Induráin, with Nelson Rodriguez on his wheel, caught Pantani, but only because Pantani was told by his director to wait for help. Still further back Bugno had lost several minutes and was going to lose his third place.

Pantani’s ascent of the Mortirolo had been jaw-dropping. The previous speed record for the climb was Chioccioli’s 15.595 kilometers per hour in the 1991 Giro, considered one of the great rides in Giro history. Pantani smashed the record, going 16.954 kilometers per hour. Italy was transfixed; more than six million Italian television viewers watched Pantani ride away from the world’s finest living stage racer.

Induráin and Pantani formed a smooth-working duo with Rodriguez sitting on. As they went through Aprica for the first time, Berzin was two minutes back and Bugno over four. Next came the Santa Cristina ascent before the finish in Aprica.

On the Santa Cristina neither Induráin nor Rodriguez, both at the end of their tethers, could contain the surging Pantani. Off he went and soloed into Aprica almost three minutes ahead of Chiappucci, the first chaser. Induráin came in 3 minutes 30 seconds after Pantani with Berzin another half-minute later. Pantani had elevated himself to second place, revealing himself as the first pure climber in the peloton since Lucien van Impe and the best since Charly Gaul. Maybe the finest ever.

Marco Pantani wins in Aprica

The new General Classification:

1. Evgeni Berzin

2. Marco Pantani @ 1 minute 18 seconds

3. Miguel Induráin @ 3 minutes 3 seconds

4. Gianni Bugno @ 4 minutes 8 seconds

5. Wladimir Belli @ 4 minutes 41 seconds

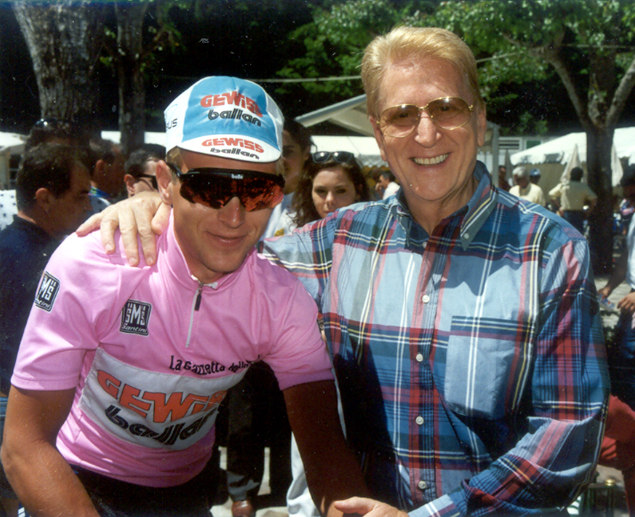

Evgeni Berzin with TV commentator Aldo Biscardi

Stage eighteen was the scene of the final time trial, a 35-kilometer hill climb leaving from the Ligurian seacoast town of Chiavari. Berzin had recovered from his hard days in the Dolomites and earned a clear-cut stage win. Induráin had indeed come to the Giro under-trained and his second place seemed to indicate he was riding into condition.

Stage twenty was the first of two days in the Alps and it packed a wallop with the Agnello before crossing to France for a trip over the Izoard, Lautaret and a finish atop Les Deux Alpes.

A small group of non-contenders went away on the Agnello and then in a flash Pantani was up to and past the break with only Hernán Buenahora glomming onto his wheel. They were together as they went up and over the Izoard with the Pink Jersey group containing Induráin and Chiappucci following at 1 minute 51 seconds. Berzin got into a spot of trouble on the Izoard ascent, but teammate Moreno Argentin led him back up to the leaders. After descending the Izoard, Pantani, seeing that the Berzin group was closing in, sat up and let Buenahora go. Buenahora was caught by those six riders from the early break who had continued riding ahead of the peloton.

For a while Berzin had only Induráin and Pantani for company on the Deux Alpes climb. Induráin tried an acceleration, but it wasn’t forceful enough to dislodge the Russian rider. In fact, Berzin answered with his own jump, which Induráin met, but Pantani was surprisingly gapped before slowly closing back up to the pair. After this the trio slowed and a few others joined them. Near the top, Poulnikov shot away from the break with Nelson Rodriguez and won the stage. Two minutes later Pantani led in Induráin and Berzin. Induráin was running out of Giro and Berzin and Pantani weren’t looking any weaker for their three weeks of racing.

The General Classification was looking good for Berzin:

1. Evgeni Berzin

2. Marco Pantani @ 2 minutes 55 seconds

3. Miguel Induráin @ 3 minutes 23 seconds

4. Pavel Tonkov @ 11 minutes 16 seconds

There was still one more Alpine stage, number twenty-one, going from Les Deux Alpes to Sestriere. It took in the Lautaret, Montgenèvre and then did a loop that had the riders doing two ascents to Sestriere. It was a frigid day, with snow in Sestriere. The top riders stuck together and despite the harrowingly cold conditions, there was no change to the upper levels of the General Classification. There was now only the ride into Milan. Berzin had become the first Russian, in fact the first eastern bloc rider, to win a Grand Tour.

Final 1994 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 100 hours 41 minutes 21 seconds

2. Marco Pantani (Carrera Jeans-Tassoni) @ 2 minutes 51 seconds

3. Miguel Induráin (Banesto) @ 3 minutes 23 seconds

4. Pavel Tonkov (Lampre) @ 11 minutes 16 seconds

5. Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera Jeans-Tassoni) @ 11 minutes 58 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Pascal Richard (GB-MG-Technogym): 78 points

2. Michele Coppolillo (Navigare-Blue Storm): 58

3. Marco Pantani (Carrera Jeans-Tassoni): 44

Points Competition:

1. Djamolidine Abdoujaparov (Polti): 202 points

2. Evgeni Berzin (Gewiss-Ballan): 182

3. Gianni Bugno (Polti): 148

Induráin’s form was indeed improving. While he won no time trials in the Giro, it was a different case in the Tour. The Spaniard humiliated the field in the Tour’s stage nine time trial. When the race hit the mountains, Induráin, who was regularly put on the ropes by the best climbers, soared with a newfound ability. He went on to take his fourth of five consecutive Tour wins.

Apparently he remembered the thrashing Pantani gave him on the Santa

Cristina and during the Tour sought to avenge himself by working hard to specifically deny Pantani any stage wins, which caused the Italian, riding his first Tour, to complain bitterly. Pantani came in third, despite a bad crash that left him weeping with pain for much of the race. Italy was enchanted. Pantani’s contract with Carrera was up at the end of 1994 and after looking at offers from other teams he signed for another two years with Boifava.

* * *

Berzin was part of one of the most successful teams of the decade, Gewiss-Ballan, which won the Giro as well as many important one-week and single day races. It is believed that the team was one of the first (but no one can really know for sure) to have a systematized doping program exploiting the performance benefits of EPO. The most extreme example of Gewiss-Ballan’s dominance was the 1994 Flèche Wallonne. The team had already won Milan–San Remo, Tirreno–Adriatico and the Critérium International. In the Flèche Wallonne, three of the team’s riders gapped the field, almost accidently, and rode a 70-kilometer team time trial to the finish. Moreno Argentin won, Giorgio Furlan was second and just a few seconds in arrears, coming in third, was Evgeni Berzin.

A test for synthetic EPO wasn’t developed until 2000. Until an upper limit on a rider’s hematocrit was established in 1997, doping with EPO was limited only by a rider's ambition and courage. Riders could use as much as they dared. Francesco Conconi, who is accused by CONI (Italian Olympic Committee) investigator Sandro Donati of introducing EPO to the pro peloton, had a brilliant assistant, Michele Ferrari, who was the Gewiss-Ballan team doctor. Ferrari famously said, “EPO is not dangerous, and that with regard to doping, anything that is not outlawed is consequently permitted.”

Records of Gewiss-Ballan rider’s hematocrits were uncovered by investigative journalists and they reveal what can only be presumed to be highly manipulated blood values. For example, the French sports newspaper L’Équipe said that in January of 1995 Berzin’s hematocrit was 41.7 percent (quite normal) and in July, during racing season, it rose to 56.3 percent. I know of no explanation for this change that excludes exogenous substances.

Gewiss-Ballan wasn’t the only offender. The other teams couldn’t let the ones with a “program” run away with everything. Soon many other squads either systematized doping within their teams (sometimes with the excuse that the riders were doping themselves with dangerous drugs and bringing it in-house under a doctor’s care reduced doping’s risk) or as they had for years, carefully turned a blind eye to their riders’ actions.

.