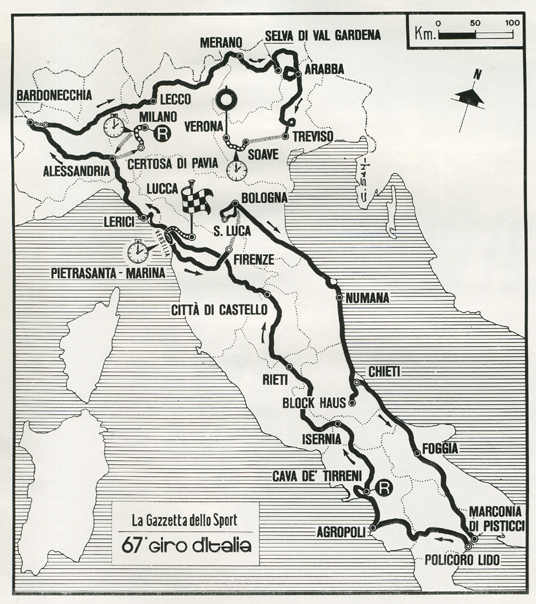

1984 Giro d'Italia

67th edition: May 17 - June 10

Results, stages with running GC, map, photos and history

1983 Giro | 1985 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1984 Giro Quick Facts | 1984 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1984 Giro d'Italia |

Map of the 1984 Giro d'Italia

3,808 km raced at an average speed of 38.68 km/hr

170 starters and 143 classified finishers

This is one of the most disputed Giri in history.

Francesco Moser and Laurent Fignon were the year's protagonists, but it seemed that at every step the officials were working to make Moser the winner.

The mysterious canceling of an ascent of the Stelvio Pass and Fignon's argument that television helicopters flew low and in front of him in the final time trial to hinder his progress are only a couple of points of disagreement.

Despite all the efforts the Giro officials went to in assisting Moser, he was able to beat the Frenchman by only 63 seconds.

Les Woodland's book Tour of Flanders: The Inside Story - The rocky roads of the Ronde van Vlaanderen is available as an audiobook here.

1984 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Francesco Moser (Gis Gelati) : 98hr 32min 20sec

Francesco Moser (Gis Gelati) : 98hr 32min 20sec- Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf) @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin (Sammontana) @ 4min 26sec

- Marino Lejarreta (Alfa Lum) @ 4min 33sec

- Johan Van der Velde (Metauro Mobili) @ 6min 56sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli (Murella-Rossin) @ 7min 48sec

- Lucien van Impe (Metauro Mobili) @ 10min 19sec

- Beat Breu (Cilo-Aufina) @ 11min 39sec

- Mario Beccia (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 11min 41ec

- Dag-Erik Pedersen (Murella-Rossin) @ 13min 35sec

- Wladimiro Panizza (Atala) @ 15min 46sec

- Eddy Schepers (Dromedario-Alan) @ 16min 55sec

- Faustino Ruperez (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 18min 2sec

- Alfredo Chinetti (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 18min 44sec

- Martial Gayant (Renault-Elf) @ 21min 10sec

- Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo) @ 22min 6sec

- Alfio Vandi (Dromedario-Alan) @ 22min 31sec

- Roberto Visentini (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 24min 7sec

- Alberto Fernandez (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 24min 39sec

- Bruno Leali (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 25min 46sec

- Charly Mottet (Renault-Elf) @ 29min 51sec

- Glauco Santoni (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 31min 9sec

- Acacio Da Silva (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 31min 25sec

- Franco Chioccioli (Murella-Rossin) @ 32min 49sec

- Luciano Loro (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 33min 2sec

- Jesús Rodriguez-Magro (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 33min 16sec

- Palmiro Masciarelli (Gis Gelati) @ 33min 37sec

- Sergio Santimaria (Del Tongo) @ 34min 8sec

- Bernard Gavillet (Cilo-Aufina) @ 36min 50sec

- Salvatore Maccali (Alfa Lum) @ 38min 20sec

- Siegfried Hekimi (Dromedario-Alan) @ 38min 22sec

- Leonardo Natale (Del Tongo) @ 41min 55sec

- Stefan Mutter (Cilo-Aufina) @ 43min 19sec

- Silvano Contini (Bianchi) @ 43min 37sec

- Seven-Ake Nilsson (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 44min 4sec

- Alessandro Paganessi (Sammontana) @ 47min 0sec

- Ennio Vanotti (Bianchi) @ 49min 12sec

- Claudio Bortolotto (Del Tongo) @ 53min 49sec

- Fabrizio Verza (Bianchi) @ 55min23sec

- Jens Veggerby (Fanini-Wührer) @ 55min 46sec

- Marino Amadori (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 0min 41sec

- Alessandro Pozzi (Bianchi) @ 1hr 0min 47sec

- Jonathan Boyer (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 1hr 3min 38sec

- Maurizio Piovani (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 3min 43sec

- Eduardo Chozas (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 1hr 5min 36sec

- Claudio Torelli (Sammontana) @ 1hr 9min 0sec

- Eric Salomon (Renault-Elf) @ 1hr 11min 36sec

- Ennio Salvador (Gis Gelati) @ 1hr 12min 4sec

- Giocondo Dalla Rizza (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 1hr 12min 57sec

- Giovanni Battaglin (Carrera-Ionoxpran) @ 1hr 14min 12sec

- Paul Wellens (Ariostea) @ 1hr 14min 51sec

- Elio Festa (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 1hr 17min 1sec

- Claudio Savini (Dromedario-Alan) @ 1hr 17min 1sec

- Godi Schmutz (Dromedario-Alan) @ 1hr 19min 29sec

- Giuseppe Petito (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 19min 29sec

- Flavio Zappi (Metauro-Mobili) @ 1hr 20min 58sec

- Roberto Ceruti (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 21min 57sec

- Amilcare Sgalbazzi (Ariostea) @ 1hr 22mn 11sec

- Hubert Seiz (Cilo-Aufina) @ 1hr 23min 5sec

- Piero Ghibaudo (Sammontana) @ 1hr 25min 17sec

- Rudy Pevenage (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 25min 46sec

- Jesús Ibañez-Loyo (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 1hr 25min 46sec

- Orlando Maini (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 28min 21sec

- Pierino Gavazzi (Atala) @ 1hr 29min 23sec

- Franco Conti (Dromedario-Alan) @ 1hr 29min 41sec

- Pierangelo Bincoletto (Metauro Mobili) @ 1hr 31min 52sec

- Luciano Rabottini (Metauro Mobili) @ 1hr 32min 34sec

- Czeslaw Lang (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 1hr 35min 20sec

- Frits Pirard (Metauro Mobili) @ 1hr 26min 5sec

- Giovanni Viero (Ariostea) @ 1hr 37min 42sec

- Daniel Willems (Murella-Rossin) @ 1hr 37min 43sec

- Steen-Michael Petersen (Fanini-Wührer) @ 1hr 39min 31sec

- Giancarlo Perini (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 1hr 42min 21sec

- Alf Segersall (Bianchi )@ 1hr 42min 57sec

- Giuliano Biatta (Fanini-Wührer) @ 1hr 46min 40sec

- Vinko Poloncic (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 1hr 47min 59sec

- Gerhard Zadrobilek (Atala) @ 1hr 49min 19sec

- Daniel Franger (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 1hr 50min 18sec

- Graziano Salvietti (Ariostea) @ 1hr 51min 3sec

- Daniel Wyder (Cilo-Aufina) @ 1hr 53min 11sec

- Valerio Piva (Bianchi) @ 1hr 54min 25sec

- Mario Polini (Murella-Rossin) @ 1hr 57min 39sec

- Dominique Gaigne (Renault-Elf) @ 1hr 58min 7sec

- Daniel Gisiger (Atala) @ 1hr 58min 53sec

- Angel Camarillo (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 1hr 59min 32sec

- Daniele Caroli (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 1hr 59min 37sec

- Antonio Ferretti (Cilo-Aufina) @ 2hr 2min 14sec

- Giovanni Moro (Ariostea) @ 2hr 2min 26sec

- Giuseppe Passuello (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 4min 59sec

- Mauro Longo (Supermercati Brionzoli) @ 2hr 5min 13sec

- Giancarlo Casiraghi (Atala) @ 2hr 8min 34sec

- Vittorio Algeri (Metauro Mobili) @ 2hr 9min 25sec

- Guido Bontempi (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 2hr 10min 27sec

- Paolo Rosola (Bianchi) @ 2hr 11min 26sec

- Benedetto Patellaro @ 2hr 13min 0sec

- Mario Noris (Atala) @ 2hr 13min 58sec

- Claudio Corti (Sammontana) @ 2hr 14min 17sec

- Urs Freuler (Atala) @ 2hr 14min 54sec

- John Eustice (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 2hr 17min 58sec

- Leonardo Bevilacqua (Malvor-Bottcchia) @ 2hr 18min 45sec

- Jesper Worre (Sammontana) @ 2hr 18min 59sec

- Michael Wilson (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 19min 55sec

- Riccardo Magrini (Metauro Mobili) @ 2hr 20min 45sec

- Giacinto Santambrogio (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 2hr 50min 50sec

- René Koppert (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 2hr 21min 12sec

- Dario Mariuzzo (Sammontana) @ 2hr 22min 19sec

- Giuseppe Martinelli (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 23min 3sec

- Philippe Chevallier (Renault-Elf) @ 2hr 25min 45sec

- Fiorenzo Favero (Sammontana) @ 2hr 25min 54sec

- Valerio Lualdi (Carrera-Inoxpran) @ 2hr 26min 52sec

- Ole Silseth (Supremercati-Brinazoli) @ 2hr 27min 27sec

- Maurizio Viotto (Bianchi) @ 2hr 28min 14sec

- Cesare Cipollini (Dromedario-Alan) @ 2hr 30min 11sec

- Marco Franceschini (Metauro Mobili) @ 2hr 30min 32sec

- Mauro Angelucci (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 30min 42sec

- Piero Onesti (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 37min 30sec

- Giovanni Renosto (Murella-Rossin)@ 2hr 39min 37sec

- Michael Carter (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 2hr 42min 52sec

- Antonio Bevilacqua (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 2hr 45min 24sec

- Stefano Giuliani (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 45min 48sec

- Jürg Bruggmann (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 2hr 47min 11sec

- Juan Fernandez (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 2hr 48min 7sec

- Philippe Saude (Renault-Elf) @ 2hr 48min 14sec

- Gianmarco Saccani (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 2hr 52min 4sec

- Carmelo Barone (Ariostea) @ 2hr 55min 55sec

- Dante Morandi (Atala) @ 2hr 56min 10sec

- Karl Maxon (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 2hr 58min 7sec

- Nazzareno Berto (Fanini-Wührer) @ 2hr 58min 14sec

- Martin Havik (Gis Gelati) @ 3hr 0min 19sec

- Luciano Lorenzi (Fanini-Wührer) @ 3hr 7min 53sec

- Luigi Ferreri (Ariostea) @ 3hr 12min 4sec

- Roberto Bressan (Murella-Rossin) @ 3hr 21min 59sec

- Marcel Russenberger (Cilo-Aufina) @ 3hr 26min 22sec

- David McFarlane (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 3hr 31min 7sec

- Marco-Antonio Lopez-Duran (Ariostea) @ 3hr 35min 47sec

- José-Luis Lopez-Cerron (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 3hr 36min 12sec

- David Akam (Gis Gelati) @ 3hr 37min 22sec

- Rudi Weber (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 3hr 38min 31sec

- Ermino Olmati (Dromedario-Alan) @ 3hr 48min 24sec

- Thierry Bolle (Cilo-Aufina) @ 3hr 53min 5sec

- Tom Ruttedge (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 3hr 54min 32sec

- Bruno Vicino (Malvor-Bottcchia) @ 4hr 13min 11sec

- Greg Saunders (Linea Italia-Motta) @ 4hr 29min 8sec

Points Competition:

Urs Freuler (Atala): 178 points

Urs Freuler (Atala): 178 points- Johan Van der Velde (Metauro Mobili): 172

- Francesco Moser (Gis Gelati): 166

- Dag-Erik Petersen (Murella-Rossin): 160

- Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf): 150

Climbers' Competition:

Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf): 53 points

Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf): 53 points- Flavio Zappi (Metauro Mobili): 40

- Moreno Argentin (Sammontana): 30

- Johan Van der Velde (Metauro Mobili): 29

- Jesús Rodríguez Magro (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor): 28

Young Rider:

Charly Mottet (Renault-Elf) 99hr 2min 11sec

Charly Mottet (Renault-Elf) 99hr 2min 11sec- Jens Veggerby (Fanini-Wührer) @ 25min 55sec

- Giocondo Dalla Rizza (Supermercati Brianzoli) @ 43min 6sec

- Elio Festa (Santini-Conti-Galli) @ 47min 10sec

- Jesús Ibañez-Loyo (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 55min 55sec

Team Time Classification:

- Renault-Elf: 293hr 48min 45sec

- Murella-Rossin @ 2min 34sec

- Carrera-Inoxpran @ 27min 41sec

Team Points Classification

- Metauro Mobili: 351 points

- Atala: 336

- Murella-Rossin: 281

1984 Giro stage results with running GC:

Thursday, May 17: Prologue, Lucca 5 km individual time trial

- Francesco Moser: 6min 14sec

- Silvestro Milani @ 11sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 12sec

- Silvano Contini @ 13sec

- Daniel Wyder @ 14sec

- Moreno Argentn s.t.

- Emanuele Bombini s.t.

- Laurent Fignon @ 16sec

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Urs Freuler @ 18sec

Friday, May 18: Stage 1, Lucca - Marina di Pietrasanta 60 km team time trial (crono a squadre)

- Renault-Elf (Wojtinek, Gayant, Fignon, Chevalier, Salomon, Gaigne, Mentheour, Mottet, Saude) 1hr 4min 13sec

- Carrera @ 6sec

- Gis Gelati @ 27sec

- Metauro Mobili s.t.

- Atala @ 30sec

- Alfa Lum @ 44sec

- Sammontana @ 47sec

- Cilo-Aufina @ 49sec

- Supermercati Brianzoli @ 1min 22sec

- Malvor-Bottecchia @ 1min 24sec

- Del Tongo @ 1min 30sec

- Dromedario-Alan @ 1min 31sec

GC after Stage 1:

- Laurent Fignon: 1hr 8min 13sec

- Francesco Moser @ 4sec

- Dominique Gaigne @ 5sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 6sec

- Charly Mottet @ 7sec

- Bruno Wojtinek, Philippe Chevalier @ 9sec

- Guido Bontempi @ 13sec

- Pierre-Henri Mentheour @ 18sec

- Bruno Leali @ 20sec

Saturday, May 19: Stage 2, Pietrasanta - Firenze, 137 km

- Urs Freuler: 3hr 15min 2sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Silvestro Milani s.t.

- Bruno Wojtinek s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Guido van Calster s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Alfredo Chinetti s.t.

- Filippo Piersanti s.t.

- Gilbert Glaus s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Laurent Fignon: 4hr 23min 15sec

- Bruno Wojtinek, Francesco Moser @ 4sec

- Dominique Gaigne @ 5sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 6sec

- Charly Mottet @ 7sec

- Philippe Chevalier @ 9sec

- Guido Bontempi @ 13sec

- Pierre-Henri Mentheour @ 18sec

- Bruno Leali @ 20sec

Sunday, May 20: Stage 3, Bologna - San Luca, 110 km

![]() Major ascents: San Luca x 3

Major ascents: San Luca x 3

- Moreno Argentin: 2hr 39min 51sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2sec

- Jesus Rodriguez @ 3sec

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5sec

- Hubert Seiz s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli s.t.

- Beat Breu @ 8sec

- Alessandro Paganessi @ 9sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 10sec

GC after Stage 3:

- Laurent Fignon: 7hr 2min 53sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 31sec

- Francesco Moser @ 35sec

- Charly Mottet @ 38sec

- Johan Van der Velde, Moreno Argentin @ 51sec

- Martial Gayant @ 54sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 59sec

- Bruno Wojtinek @ 1min 0sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 1min 9sec

Monday, May 21: Stage 4, Bologna - Numana, 238 km

- Stefan Mutter: 6hr 4min 33sec

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Giovanni Mantovani s.t.

- Guido Van Calster s.t.

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Jürg Bruggmann s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Nazzareno Berto s.t.

- Guido Bontempi s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Laurent Fignon: 13hr 7min 26sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 31sec

- Francesco Moser @ 35sec

- Charly Mottet @ 38sec

- Johan Van der Velde, Moreno Argentin @ 51sec

- Martial Gayant @ 54sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 59sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 1min 9sec

- Philippe Chevalier @ 1min 12sec

Tuesday, May 22: Stage 5, Numana - Block Haus, 198 km

![]() Major ascent: Block Haus

Major ascent: Block Haus

- Moreno Argentin: 5hr 40min 11sec

- Francesco Moser @ 2sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 3sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 6sec

- Jesus Rodriguez @ 10sec

- Beat Breu s.t.

- Roberto Visentini s.t.

- Mario Beccia s.t.

- Silvano Contini @ 24sec

- Vinko Poloncic @ 39sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 1sec

GC after Stage 5:

- Francesco Moser: 19hr 47min 59sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 9sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 19sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 43sec

- Marino Lejaretta @ 55sec

- Beat Breu @ 1min 29sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 34sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 1min 36sec

- Mario Beccia @ 1min 46sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 48sec

Wednesday, May 23: Stage 6, Chieti - Foggia, 195 km

- Francesco Moser: 5hr 28min 8sec

- Gilbert Glaus s.t.

- Pierangelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Francesco Moser: 24hr 15min 47sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 29sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 39sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 3sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 15sec

- Beat Breu @ 1min 49sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 1min 56sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 6sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 8sec

Thursday, May 24: Stage 7, Foggia - Marconia di Pisticci, 226 km

- Urs Freuler: 5hr 56min 33sec

- Giovanni Mantovani

- Nazzareno Berto s.t.

- Bruno Wojtinek s.t.

- Dante Morandi s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Godi Schmutz s.t.

- Dario Mariosso s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Sten Petersen s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Francesco Moser: 30hr 12min 20sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 29min

- Roberto Visentini @ 39sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 3sec

- Marino Lejaretta @ 1min 15sec

- Beat Breu @ 1min 49sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 1min 56sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 6sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 8sec

Friday, May 25: Stage 8, Policoro Lido - Agripoli, 231 km

![]() Major ascents: Faggeto, Santinella

Major ascents: Faggeto, Santinella

- Urs Freuler: 5hr 57min 38sec

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Mauro Longo s.t.

- Giuseppe Martinelli s.t.

- Guido Bontempi s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Francesco Moser: 36hr 9min 48sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 49sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 13sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 25awx

- Beat Breu @ 1min 51sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 2min 4sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 16sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 18sec

Saturday, May 26: Stage 9, Agropoli - Cava dei Tirreni, 105 km

![]() Major ascent: Chiunzi

Major ascent: Chiunzi

- Dag Erik Pedersen: 2hr 23min 25sec

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

- Hubert Seiz s.t.

- Faustino Ruperez s.t.

- Moreno Agentin @ 4sec

- Marino Amadori s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Francesco Moser: 38hr 33min 17sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 49sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 54sec

- Marino Lejaretta @ 1min 25sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 2min 4sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 4sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 16sec

Sunday, May 27: Stage 10: Cava dei Terreni - Isernia, 209 km

(one source has this as the first rest day)

![]() Major ascents: Miralago, Perrone

Major ascents: Miralago, Perrone

- Martial Gayant: 5hr 40min 57sec

- Charly Mottet @ 19sec

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Moreno Argentin @ 23sec

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Guido Van Calster s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Francesco Moser: 44hr 14min 37sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 49sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 54sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 35sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 2min 7sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 8sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 14sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 16sec

Monday, May 28: Stage 11, Isernia - Rieti, 243 km

- Urs Freuler: 6hr 27min 55sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Guido Van Calster s.t.

- Piernagelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Mauro Longo s.t.

- Bruno Tojtinek s.t.

- Giuseppe Martinelli s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Francesco Moser: 50hr 42min 32sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 49sec

- Laurnet Fignon @ 54sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 35sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 14sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 16sec

Tuesday, May 29: Rest Day (giorno di riposo) one source has the first rest day on the 27th

Wednesday, May 30: Stage 12, Rieti - Città di Castello, 178 km

- Paolo Rosola: 4hr 7min 0sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 15sec

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Giuseppe Martinelli s.t.

- Luciano Rabottini s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Francesco Moser: 54hr 49min 32sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 49sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 54sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 35sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Bear Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 14sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 16sec

Thursday, May 31: Stage 13, Città di Castello - Lerici, 269 km

![]() Major ascent: Montemarcello

Major ascent: Montemarcello

- Roberto Visentini: 7hr 27min 0sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 19sec

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Alfio Vandi s.t.

- Charly Mottet s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Francesco Moser: 62hr 16min 51sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 10sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 34sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 39sec

- Marino Lejaretta @ 1min 35sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 43sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 2min 54sec

Friday, June 1: Stage 14, Lerici - Alessandria, 205 km

![]() Major ascents: Bracco, Scoffera

Major ascents: Bracco, Scoffera

- Sergio Santimaria: 4hr 40min 20sec

- Pierre-Henri Mentheour @ 15sec

- Emanuele Bombini @ 24sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 48sec

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

- Flavio Zappi s.t.

- Rudy Pevenage s.t.

- Glauco Sanotni s.t.

- Urs Freuler @ 2min 55sec

- Giovanni Mantovani s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Francesco Moser: 67hr 0min 26sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 10sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 34sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 39sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 35sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 1min 54sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2min 6sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 10sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 43sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 2min 54sec

Saturday, June 2: Stage 15, Certosa di Pavia - Milano 37 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Francesco Moser 47min 39sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 53sec

- Urs Freuler @ 1min 15sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 18sec

- Daniel Willems @ 1min 19sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 1min 21sec

- Czeslaw Lang @ 1min 24sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 28sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 33sec

- Siegfried Hekimi @ 1min 40sec

GC after Stage 15

- Francesco Moser: 67hr 48min 5sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin, Laurent Fignon @ 2min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 3min 31sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 30sec

- Marioo Beccia @ 4min 31sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 4min 53sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 15sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 5min 24sec

Sunday, June 3: Stage 16, Alessandria - Bardonnecchia, 200 km.

(one source has this as the second rest day)

![]() Major ascent: Jaffereau

Major ascent: Jaffereau

- Erik Pedersen: 5hr 27min 3sec

- Alfredo Chinetti @ 3sec

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Bernard Gavillet @ 5sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ s.t.

- Charly Mottet s.t.

- Moreno Argentin @ 10sec

- Frits Pirard @ 11sec

- Gerhard Zadrobilek s.t

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Francesco Moser: 73hr 15min 19sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 2min 6sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 7sec

- Marino Lejaretta @ 3min 25sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 12sec

- Mario Beccia @ 4min 44sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 5min 3sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 15sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 5min 24sec

Monday, June 4: Stage 17, Bardonecchia- Lecco, 238 km

- Jürg Bruggmann: 6hr 46min 27sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 2sec

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Gerhard Zadrobilek s.t.

- Marino Lejaretta s.t.

- Cesare Cipollini s.t.

- Giovanni Mantovani s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Francesco Moser: 80hr 1min 48sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 3sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 3min 25sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 7sec

- Mario Beccia @ 4min 44sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 4min 48sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 15sec

- Gioseppe Saronni @ 5min 24sec

Tuesday, June 5: Stage 18, Lecco - Merano, 252 km

![]() Major ascent: Tonale

Major ascent: Tonale

- Bruno Leali: 6hr 15min 19sec

- Erik Pedersen @ 5sec

- Maurizio Piovani s.t.

- Martial Gayant s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Danieli Caroli s.t.

- Alfredo Chnetti s.t.

- Salvatore Maccali s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Francesco Moser: 86hr 17min 12sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 2min 6sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 3min 25sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 7sec

- Mario Beccia @ 4min 44sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 4min 48sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 15sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 5min 24sec

Wednesday, June 6: Rest Day (giorno di riposo). One source has the second rest day falling on the June 3.

Thursday, June 7: Stage 19: Merano - Selva di Val Gardena, 76 km

![]() Major ascent: Selva di Val Gardena

Major ascent: Selva di Val Gardena

- Marino Lejarreta: 1hr 56min 41sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 8sec

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli s.t.

- Lucien van Impe s.t.

- Mario Beccia s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Beat Breu s.t.

- Faustino Ruperez s.t.

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Francesco Moser: 88hr 15min 50sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 3sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 8sec

- Mario Beccia @ 3min 55sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 4min 21sec

- Beat Breu @ 4min 43sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 57sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 5min 27sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 5min 28sec

Friday, June 8: Stage 20, Selva di Val Gardena - Arabba, 169 km

![]() Major ascents: Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Campolongo

Major ascents: Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Campolongo

- Laurent Fignon: 4hr 30min 24sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 20sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 52sec

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Luciano Loro @ 1min 54sec

- Lucien van Impe s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Francesco Moser @ 2min 19sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 2min 20sec

- Beat Breu @ 2min 29sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Laurent Fignon: 92hr 47min 9sec

- Francesco Moser @ 1min 31sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 56sec

- Morino Lejaretta @ 2min 9sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 9sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 48sec

- Beat Breu @ 6min 19sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 6min 46sec

- Mario Beccia @ 8min 25sec

- Erik Pedersen @ 9min 23sec

Saturday, June 9: Stage 21, Arabba - Treviso, 205 km

- Guido Bontempi: 4hr 54min 24sec

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Erik Pedersen s.t.

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Mauro Longo s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Jens Veggerby s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Laurent Fignon: 97hr 41min 33sec

- Francesco Moser: 1min 21sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 56sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 2min 9sec

- Johan Van der Velde @ 4min 9sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 48sec

- Beat Breu @ 6min 19sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 6min 48sec

- Mario Beccia @ 8min 25sec

- Erik Pedersen @ 9min 17sec

Sunday, June 10: 22nd and Final Stage, Soave - Verona 42 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Francesco Moser: 49min 26sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 24sec

- Daniel Gisiger @ 2min 38sec

- Urs Freuler @ 2min 44sec

- Daniel Willems @ 2min 48sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 3min 21sec

- Czeslaw Lang @ 3min 39sec

- Siegfried Hekimi @ 3min 41sec

- Charly Mottet, Marino Lejarreta @ 3min 45sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 3min 51sec

The Story of the 1984 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audibook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Torriani was acutely aware that his countrymen were passionate about wanting to have an Italian winner. In 1984 the best Italian stage racers were still thought to be Moser and Saronni.

So Torriani again laid out a rather flat course, in the words of racing historian and journalist Pierre Chany, “to favor either Saronni or Moser.” Racer Mario Beccia, the leader of the Malvor team and a competent climber, echoed those thoughts. Even Moser had reservations about the generous time bonuses in play for stage wins in the 1984 edition.

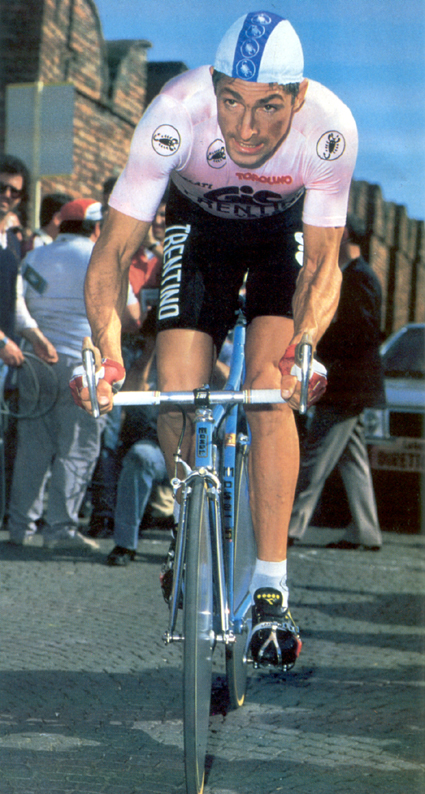

Moser himself was in top form, having won the most coveted of all single-day Italian races, Milan–San Remo; and even more extraordinary, using an aerodynamic bike, he had smashed Eddy Merckx’s world hour record. It was an impressive career renaissance. Only later did the world learn that Moser had blood-doped (reinjecting his own saved blood), not a banned practice at that time, to beat the hour record. And the other races he won during his late-career bloom, who knows? He was being trained by Francesco Conconi and we’ll have more about Signor Conconi later.

The man who could offer the greatest challenge to the two Italian gentlemen was Frenchman Laurent Fignon, nicknamed “The Professor” because he had attended college for a while and wore glasses, both rarities in the 1984 peloton. Fignon won the Tour in his first attempt, in 1983. Not only had Fignon won it, he won it with startling ease. He had stalked Pascal Simon, the leader for much of the race, who was suffering from an extremely painful broken shoulder blade, waiting for him to abandon, which he eventually did. Moreover, Fignon was both good against the clock and an excellent climber, a true passista-scalatore.

This Giro and the accusations that the organizers (meaning Torriani) took an active part in influencing the outcome of the 1984 Giro has been the subject of spirited (meaning shouting and bulging veins) discussion ever since the winner was given his final maglia rosa.

We’ll start with the route itself. It had a healthy 140 kilometers of individual time trialing, which worked to Moser’s advantage. On the other hand there was a team time trial, where the Fignon-led Renault riders could be expected to do very well. And the climbing, where Fignon enjoyed a marked superiority over Moser, leaned to Fignon’s advantage because of a planned ascent of the Stelvio in stage eighteen.

The other major climbing stage, with the short climbs around the Gruppo Sella in the Dolomites, was unlikely to allow Fignon to permanently dispatch Moser. On paper then, it looked that Fignon’s only chance to win would involve a heroic climb up the Stelvio, but because of the way the stage was designed, even that looked iffy.

No other rider on the start list seemed to be on the level of Fignon and Moser. 1984 wasn’t Saronni's year and he couldn't be expected to time-trial or climb well enough to beat the two favorites. Neither Baronchelli (still riding reasonably well) nor Battaglin (in his last year as a pro) were on the level of these two at this point. Van Impe was the Belgian Champion and had finished fourth in the 1983 Tour, a big improvement over his ninth in the 1983 Giro, but his fourth place was to Fignon.

The race started in Lucca and Moser, as expected, won the 5-kilometer prologue time trial, with Fignon eighth at 16 seconds. Fignon’s well-drilled Renault squad won the team time trial the next day, but the team time trial’s real times did not count towards the General Classification, though first place was good for a 2 minute 30 second bonification. Moser’s Gis team was third, their bonus being 2 minutes 10 seconds, netting Fignon 20 seconds over Moser and the lead, by 4 seconds.

He slightly increased his lead in stage three, a circuit race in Bologna that included a stiff little climb that let Fignon put another 16 seconds plus a 15-second time bonus for second place between himself and Moser.

An American team, Linea Italia-Motta (run by professional cycling’s first-ever female manager, Robin Morton), was entered, and a member of the squad, Karl Maxon, managed to become the virtual Pink Jersey in stage four when he gained 22 minutes in a solo break. Saronni’s efforts to leave Fignon for dead when the Frenchman crashed enlivened the field and kept Maxon from winning the stage.

Stage five should have been Fignon’s chance to hammer Moser back down the standings because it finished at the top of Block Haus. For a while it looked like Fignon, who was leading the front group, was going to do something special, but about four kilometers from the summit he was done in by hunger knock and struggled to the top. Moser, on the other hand, was having a terrific day and narrowly lost the stage win to Moreno Argentin. Fignon had to concede 88 seconds and the lead to Moser.

Francesco Moser in action

There was a crash on a badly marked corner during a descent in stage seven. The riders were incensed over the dangerous oversight and rode slowly the rest of the way to the finish. Almost all the riders, that is. Swiss sprinter Urs Freuler, seeing an easy stage win, jumped ahead of the striking riders.

The Giro reached the arch of the boot at the end of stage seven and headed up the western side of Italy. Still, Moser remained the maglia rosa with nothing happening to change the top ranks of the standings, which remained close. The first 25 riders were all within five minutes of Moser.

At the start of stage nine, Murella withdrew its team from the Giro to punish its stage seven striking riders, taking out Baronchelli. The Murella riders announced they would continue riding the Giro, even at their own expense. To prove their worthiness, the Murella riders rode the stage like fiends with Baronchelli attacking hard several times and finally setting up his teammate Dag Erik Pedersen for the stage win. Having proven himself to be a master manipulator (I’m sure he would have considered “motivator” to be a more accurate term), team director Luciano Pezzi concluded the Murella soap opera by ending his threat to withdraw.

But the polemiche were not finished. Felice Gimondi had resigned as president of the Italian Professional Riders Association to protest what he thought was a stupid strike, and vice-president Vittorio Adorni joined him. Incensed that their organization hadn’t stood with them, the riders decided that future officers must be currently racing to hold office.

There was much noise, but the racing over unchallenging roads generated little heat. The race was back in northern Italy for the stage fifteen time trial going from the Certosa di Pavia to Milan. Before the 37-kilometer stage was run, the General Classification stood thus:

1. Francesco Moser

2. Roberto Visentini @ 10 seconds

3. Moreno Argentin @ 34 seconds

4. Laurent Fignon @ 39 seconds

Moser won the time trial, beating Visentini by 53 seconds and Fignon by 88 seconds, yielding the following standings:

1. Francesco Moser

2. Roberto Visentini @ 1 minute 3 seconds

3. Moreno Argentin and Laurent Fignon tied @ 2 minutes 7 seconds

Fignon and Visentini started to divide up the Giro’s spoils, both expressing confidence that the coming mountain stages would surely be the scene of Moser’s downfall. Yet, Fignon later wrote that with each passing day he could see that Moser was getting stronger and more confident.

Cue ominous background sound of cellos playing minor chords. News came that the Stelvio was blocked with snow, but would be ready for stage eighteen. After stage seventeen was completed, the word was the Stelvio was not yet passable.

Now here’s where it gets complicated. Torriani had photos proving that it would be easy to clear the Stelvio and said he badly wanted the race to go over the pass. It was said that a government worker in Trent (Moser’s home town) refused to allow the Giro to go over the Stelvio. Who, in writer Samuel Abt’s words, evaporated the stage? I don’t know.

To substitute, the race went over the Tonale and Palade Passes. Visentini, believing that the fix was in, quit the race after the stage. Fignon felt that even with the Stelvio eliminated, there was enough climbing left to give him a fair shot at the race.

Fignon tried to get away on the Tonale, but couldn’t. He did cause Moser to get dropped, however. But Moser, a fine descender, got back on and apparently Fignon did not attack on the Palade.

The French erupted with white-hot fury after the stage was over. Fignon’s director Cyrille Guimard said that Moser had been pushed by both spectators and riders and that when he had been dropped, he had been allowed to draft follow cars to regain contact. Moser didn’t directly deny the charges, and there was no adjustment to Moser’s time, as the Giro had done in decades past. To rub salt in the wound, the race jury penalized Fignon twenty seconds for taking food outside the feed zone. Cynics noted that this was a hard mountain stage that, strangely, had 46 riders finish within 5 seconds of stage winner Bruno Leali.

Stage nineteen was run without drama. Fignon left Moser 49 seconds behind going into Selva di Val Gardena. This tightened things up, and with the five-pass stage coming next, here were the standings:

1. Francesco Moser

2. Laurent Fignon @ 1 minute 3 seconds

3. Moreno Argentin @ 1 minute 7 seconds

4. Marino Lejarreta @ 1 minute 8 seconds

5. Mario Beccia @ 3 minutes 55 seconds

The twentieth stage was the last chance for the climbers, with the Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, Gardena and again the Campolongo passes. The 169-kilometer stage wasn’t the pure climber’s play because this classic loop of shorter, hard climbs can give a good descender a chance to regain contact before the next climb hits. Fignon escaped on the Pordoi and no one was able to catch him. He sailed into Arabba 2 minutes 19 seconds ahead of Moser, who came in eighth. Fignon took the lead, 1 minute 31 seconds ahead of Moser.

The 1984 Giro d’Italia came down to the final time trial, 42 kilometers from Soave to Verona. Moser won it riding a road version of his aerodynamic World Hour Record bike with the remarkable time of 49 minutes 26 seconds. Fignon came in second, 2 minutes 24 seconds slower. Moser had gone at a blistering 50.977 kilometers an hour, the fastest-ever time trial longer than 20 kilometers.

That remarkable time trial ride gave the 1984 Giro to Moser.

Moser finishes his time trial in the Verona arena

The recriminations over this Giro continue to this day. There are three areas of controversy: the biased officiating that allowed Moser to be pushed up the mountains and draft the caravan cars, the elimination of the Stelvio climb, and problems with the final time trial.

It would appear that Moser did benefit from officials who turned a blind eye to the illicit help he received, yet they were quite willing to penalize others. Without a doubt, Fignon was hometowned.

The Stelvio question remains a muddle. Was the pass closed? The French magazine Vélo published pictures showing the Stelvio was open. If the Stelvio did have snow, it wasn’t much and clearing the summit would have been simple. The Giro organization seemed to be quite happy to save the big, muscular Moser the trouble of going up the mountain.

It is not clear to me that Fignon would have been able to take a lot of time out of Moser if the Stelvio had been run. The stage was scheduled to be run from the less challenging south-facing side, not the legendary 48-switchback Trafoi climb. After cresting the pass, the riders would have had a long technical descent and then a 50-kilometer flat run-in to Merano. Would Fignon have been able to hold a large gap on the descent and the road to Merano from Moser who was both a skilled descender and the superior time trialist? It’s all conjecture but in my opinion if Fignon had been able to create a gap on the ascent, it probably would have been erased by the time the he arrived in Merano.

The final time trial where Moser took the Pink Jersey from Fignon has problems, unless you are Francesco Moser. As Fignon told historian Les Woodland in a Procycling magazine interview, “In the time trial, just get out the tapes from the television and see for yourself. It’s very clear. The television helicopter was flying just behind him. You can see from the images. They are all from low down and behind him, so that the blades of the helicopter were pushing him along. Then look at the pictures of me and they’re all taken from in front of me, so that while the helicopter was pushing Moser along, it was pushing me back.” Fignon later said the turbulence from the helicopter came close to knocking him off his bike a couple of times. Furthermore, Moser rode the time trial strangely, staying in the center of the road, even in the corners where shooting the apex would have shortened his distance, which all professional riders normally do.

Moser countered, “Listen, the helicopter simply could not have flown that low. It would have had to have been just above our heads to make a difference. The story is so stupid because it’s just impossible.”

Clearly irritated by what he sees as French disinformation, in another interview he said, “One must remember the crono was in Verona on roads lined with trees and buildings.” He further said that the helicopter was flying around all day, filming most of the riders but that he only noticed it in the last 100 meters or so. He said that even if it was trying to blow him along, it wasn’t around long enough to make any difference. Further, it must be noted that Moser had soundly trounced Fignon in the stage fifteen time trial by a solid 88 seconds. He was the better man against the clock and Fignon said Moser was getting stronger as the Giro progressed.

The president of the race jury, a Belgian, said he followed Moser and that the helicopter in no way aided the Italian. He further remarked that he had never seen a rider go so hard in a time trial.

Moser is adamant that he won the race because he was the strongest while Fignon died believing he was robbed of victory in the Giro.

Francesco Moser finally wins the Giro d'Italia

Final 1984 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Francesco Moser (GIS-Tuc Lu) 98 hours 32 minutes 20 seconds

2. Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf) @ 1 minute 3 seconds

3. Moreno Argentin (Sammontana) @ 4 minutes 26 seconds

4. Marino Lejarreta (Alfa Lum-Olmo) @ 4 minutes 33 seconds

5. Johan Van der Velde (Metauro Mobili) @ 6 minutes 56 seconds

Climbers’ Competition

1. Laurent Fignon (Renault-Elf): 53 points

2. Flavio Zappi (Metauro Mobili): 40

3. Moreno Argentin (Sammontana): 30

Points Competition:

1. Urs Freuler (Atala-Campagnolo): 178 points

2. Johan Van der Velde (Metauro Mobili): 172

3. Francesco Moser (GIS-Tuc Lu): 166

Winning a Grand Tour can require perfection in all the details. Fignon’s final deficit was slightly more than the 88 seconds he lost by not eating enough on the way to Block Haus. He did, though, go on to deliver a splendid performance in the Tour, easily beating Bernard Hinault by over ten minutes.

.