1983 Giro d'Italia

66th edition: May 12- June 5

Results, stages with running GC, map, photos and history

1982 Giro | 1984 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1983 Giro Quick Facts | 1983 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1983 Giro d'Italia

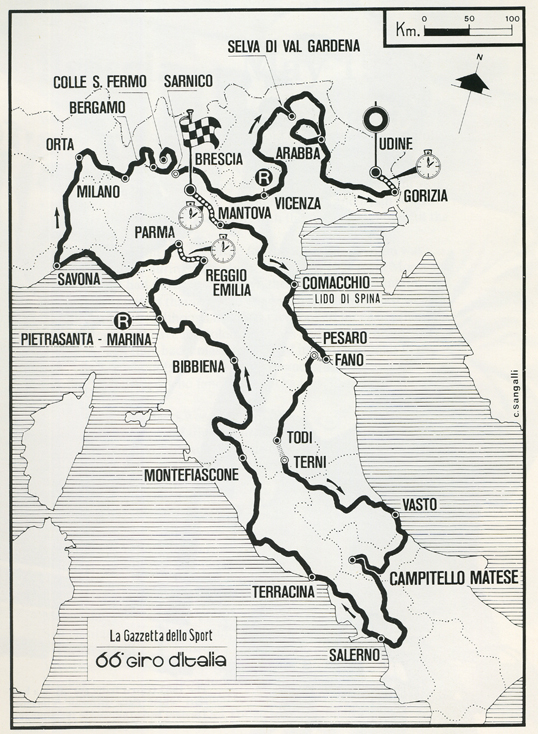

Map of the 1983 Giro d'Italia

3,922 km raced at an average speed of 38.94 km/hr

162 starters and 140 classified finishers

The 1983 route was probably the least challenging post-war route, with only one hard day in the mountains.

This was done to assist the two best Italian racers of the time, Francesco Moser and Giuseppe Saronni.

Neither were outstanding climbers.

With the generous time bonuses in play, even for the time trials, Saronni won a Giro d'Italia tailor-made for him.

Les Woodland's book Tour de France: The Inside Story - Making the World's Greatest Bicycle Race is available as an audiobook here.

1983 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo) 100hr 45min 30sec

Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo) 100hr 45min 30sec- Roberto Visentini (Inoxpran) @ 1min 7sec

- Alberto Fernández (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 3min 40sec

- Mario Beccia (Malvor) @ 5min 55sec

- Dietrich Thurau (Del Tongo) @ 7min 44sec

- Marino Lejarreta (Alfa Lum) @ 7min 47sec

- Faustino Rupérez (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 8min 24sec

- Eduardo Chozas (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 9min 41sec

- Lucien van Impe (Metauro Mobili) @ 10min 54sec

- Wladimiro Panizza (Atala) @ 12min 0sec

- Pedro Munoz (Geneaz-Cusin-Zor) @ 12min 26sec

- Eddy Schepers (Hoonved-Almoda) @ 13min 3sec

- Jean-René Bernaudeau (Wolber) @ 13min 42sec

- Jostein Wilmann (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 14min 18sec

- Tommy Prim (Bianchi) @ 15min 11sec

- Franco Chioccioli (Vivi-Benotto) @ 15min 22sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli (Sammontana) @ 15min 57sec

- Luciano Loro (Inoxpran) @ 15min 58sec

- Alvaro Pino (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 19min 6sec

- Bruno Leali (Inoxpran)@ 19min 24sec

- Alfio Vandi (Metauro Mobili)@ 22min 25sec

- Emanuele Bombini (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 23min 14sec

- Fabrizio Verza (Gis Gelati) @ 22min 25sec

- Christian Seznec (Wolber) @ 28min 46sec

- Dominique Arnaud (Wolber) @ 31min 2sec

- Graham Jones (Wolber) @ 31min 23sec

- Sven-Ake Nilsson (Tremolan-Galli) @ 31min 32sec

- Ismaël Lejarreta (Alfa Lum) @ 32min 6sec

- Alessandro Paganessi (Bianchi) @ 32min 15sec

- Harald Maier (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 35min 54sec

- Leonardo Natale (Del Tongo) @ 36min 44sec

- Marc Sergeant (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 39min 29sec

- Palmiro Masciarelli (Gis Gelati) @ 41min 39sec

- Claudio Bortolotto (Del Tongo) @ 44min 20sec

- Patrick Bonnet (Wolber) @ 44min 54sec

- Ennio Vanotti (Bianchi) @ 45min 48sec

- Davide Cassani (Termolan-Galli) @ 45min 49sec

- Frits Pirard (Metauri Mobili) @ 48min 21sec

- Jean-François Rodriguez (Wolber) @ 48min 24sec

- Czeslaw Lang (Gis Gelati) @ 50min 36sec

- Luc Govaerts (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 52min 21sec

- Stefan Mutter (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 53min 0sec

- Ettore Bazzichi (Dromedario-Alan) @ 53min 27sec

- Giuseppe Lanzoni (Termolan-Galli) @ 53min 39sec

- Moreno Argentin (Sammontana) @ 53min 44sec

- Franco Conti (Dromedario-Alan) @ 55min 7sec

- Roberto Ceruti (Del Tongo) @ 58min 24sec

- Giacinto Santambrogio (Mareno-Willier Triestina) @ 59min 34sec

- Fons de Wolf (Bianchi) @ 1hr 3min 25sec

- Claudio Savini (Dromedario-Alan) @ 1hr 3min 38sec

- Fiorenzo Aliverti (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 5min 10sec

- Antonio Bevilacqua (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 1hr 10min 54sec

- Paul Wellens (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 1hr 12min 0sec

- Silvano Ricco (Termolan-Galli) @ 1hr 12min 25sec

- Piero Ghibaudo (Gis Gelait) @ 1hr 17min 7sec

- Tullio Bertacco (Bianchi) @ 1hr 17min 57sec

- Francesco Masi (Mareno-Wilier-Triestina) @ 1hr 22min 19sec

- Pierre-Raymond Villemiane (Wolber) @ 1hr 27min 24sec

- Salvatore Maccali (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 27min 56sec

- Amilcare Sgalbazzi (Sammontana) @ 1hr 28min 7sec

- Michael Wilson (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 28min 22sec

- Gerhard Zadrobilek (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 1hr 28min 22sec

- Luciano Rabottini (Metauro Mobili) @ 1hr 28min 48sec

- Mario Polini (Sammontana) @ 1hr 29min 19sec

- Giuliano Biatta (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 1hr 31min 57sec

- Jésus Ibanez-Loyo (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 1hr 35min 14sec

- Alfredo Chinetti (Inoxpran) @ 1hr 37min 43sec

- Marino Amadori (Gis Gelati) @ 1hr 38min 1sec

- Ludo Loos (Hoonved-Almoda) @ 1hr 38min 20sec

- Guido Van Calster (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 40min 8sec

- Riccardo Magrini (Metauro mobili) @ 1hr 40min 32sec

- Vinko Poloncik (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 1hr 42min 26sec

- Bruno Wolfer (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 1hr 43min 33sec

- Daniel Gisiger (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 1hr 49min 10sec

- Claude Vincendeau (Wolber) @ 1hr 49min 31sec

- Gregor Braun (Vivi-Benotto) @ 1hr 49min 56sec

- Giuseppe Petito (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 51min 39sec

- Alf Segersall (Bianchi) @ 1hr 57min 27sec

- Flavio Zappi (Metauro Mobili) @ 1hr 59min 40sec

- Erminio Rizzi (Termolan-Galli) @ 1hr 59min 58sec

- Walter Clivati (Mareno-Wilier Triestina)@ 2hr 1min 8sec

- Ennio Salvador (Gis Gelati) @ 2hr 1min 17sec

- Claudio Torelli (Sammontana) @ 2hr 1min 33sec

- Valerio Lualdi (Inoxpran) @ 2hr 2min 2sec

- Sergio Santimaria (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 3min 20sec

- Cesare Cipollini (Dromedario-Alan) @ 2hr 4min 8sec

- Giocondo Dalla Rizza (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 2hr 6min 17sec

- Jesper Worre (Sammontana) @ 2hr 7min 50sec

- Giuseppe Passuello (Vivi-Benotto) @ 2hr 8min 18sec

- Giancarlo Casiraghi (Atala) @ 2hr 9min 58sec

- Urs Freuler (Atala) @ 2hr 11min 1sec

- Angel Camarillo (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 2hr 11min 25sec

- Giuseppe Montella (Dromedario-Alan) @ 2hr 19min 35sec

- Francesco Caneva (Termolan-Galli) @ 2hr 21min 43sec

- Raniero Gradi (Sammontana) @ 2hr 22min 41sec

- Maurizio Piovani (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 23min 16sec

- Acacio Da Silva (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 2hr 23min 40sec

- Pierino Gavazzi (Atala) @ 2hr 24min 8sec

- Daniele Caroli (Termolan-Galli) @ 2hr 25min 20sec

- Giuliano Pavanello (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 2hr 26min 58sec

- Fritz Werhli (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 2hr 29min 56sec

- Mario Noris (Atala) @ 2hr 30min 14sec

- Mauro Angelucci (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 30min 16sec

- Pierangelo Bincoletto (Metauro Mobili) @ 2hr 33min 40sec

- Mario Bonzi (Vivi-Benotto) @ 2hr 34min 7sec

- Rudy Pevenage (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 34min 48sec

- Sergio Parsani (Bianchi) @ 2hr 35min 35sec

- Orlando Maini (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 40min 9sec

- Claudio Corti (Sammontana) @ 2hr 41min 15sec

- Piero Onesti (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 43min 4sec

- Paolo Rosola (Atala) @ 2hr 43min 19sec

- Valerio Piva (Bianchi) @ 2hr 44min 16sec

- Fiorenzo Favero (Sammontana) @ 2hr 45min 59sec

- Frank Hoste (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 2hr 49min 36sec

- Gianluigi Zuanel (Vivi-Benotto) @ 2hr 55min 54sec

- José-Luis Lopez-Cerron (Gemeaz cusin-Zor) @ 3hr 2min 5sec

- Graziano Salvietti (Vivi-Benotto) @ 3hr 3min 3sec

- Fabien De Vooght (Wolber) @ 3hr 4min 19sec

- Gianmarco Saccani (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 3hr 4min 59sec

- Leonardo Bevilacqua (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 3hr 9min 25sec

- Patrick Hermans (Hoonved-Almoda) @ 3hr 13mn 29sec

- Nazzareno Berto (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 3hr 15min 36sec

- Josef Jacobs (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 3hr 15min 42sec

- Peter Kehl (Dromedario-Alan) @ 3hr 16min 56sec

- Marc Vendenbrande (Hoonved-Almoda) @ 3hr 30min 2sec

- Carmelo Barone (Dromedario-Alan) @ 3hr 20min 38sec

- Hans Neumayer (Hoonved-Almoda) @ 3hr 20min 40sec

- Marc Somers (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 3hr 22min 45sec

- Daniele Antinori (Mareno-Wilier Triestina) @ 3hr 26min 58sec

- Giovanni Viero (Vivi-Benotto) @ 3hr 27min 20sec

- Corrado Donadio (Vivi-Benotto) @ 3hr 29min 2sec

- Jörg Bruggmann (Bottecchia-Malvor) @ 3hr 31min 8sec

- Dirk Wayenberg (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 3hr 33min 13sec

- Carlo Tonon (Inoxpran) @ 3hr 33min 56sec

- Luigi Trevellin (Dromedario-Alan) @ 3hr 37min 16sec

- Walter Delle Case (Atala) @ 3hr 37min 54sec

- Jan Bogaert (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 3hr 51min 42sec

- Dante Morandi (Gis Gelati) @ 3hr 57min 22sec

- Etienne De Beule (Europ Decor-Dries) @ 4hr 10min 10sec

- Claudio Girlanda (Termolan Galli) @ 4hr 14min 17sec

Points Competition:

Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo): 223 points

Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo): 223 points- Moreno Argentin (Sammontana): 149

- Frank Hoste (Europ Decor-Dries): 139

- Pierino Gavazzi (Atala): 120

- Stefan Mutter (Magniflex-Eorotex): 111

Climbers' Competition:

Lucien van Impe (Metauro Mobili): 70 points

Lucien van Impe (Metauro Mobili): 70 points- Alberto Fernández (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor): 43

- Marino Lejarreta (Alfa Lum): 27

- Faustino Rupérez (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor): 27

- Alessandro Paganessi (Bianchi): 23

Young Rider

Franco Chioccioli (Vivi-Benotto) 101hr 0min 52sec

Franco Chioccioli (Vivi-Benotto) 101hr 0min 52sec- Fabrizio Verza (Gis Gelati) @ 12min 16sec

- Harald Maier (Magniflex-Eorotex) @ 20min 32sec

- Davide Cassani (Termolan-Galli) @ 30min 27sec

- Czeslaw Lang (Gis Gelati) @ 35min 13sec

Team Classification:

- Gemeaz Cusin-Zor

- Inoxpran @ 10min 35sec

- Del Tongo @ 17min 30sec

1983 Giro stage results with running GC:

Friday, May 13: Stage 1, Brescia - Mantova 70 km team time trial (cronometro a squadre). Time bonuses down to 15th place, starting with 2min 30sec for first.

- Bianchi (Prim, Vanoni, Segersall, Paganessi, Contini, Parsani, Piva) 1hr 17min 48sec

- Atala (Freuler, Noris, Gavazzi, Renosto, Panizza, Rosola, Casiraghi, Delle Case, Angeli) @ 32sec

- Gis Gelati (Moser, Lang, Masciarelli, Verza, Salvador, Amadori) @ 38sec

- Sammontana (Baronchelli, Argentin, Torelli, Corti, Sgalbazzi, Worre, Gradi, Polini) @ 46sec

- Del Tongo (Saronni, Thurau, Bortolotto, Pevenage, Natali, Piovani) @ 48sec

- Inoxpran (Bontempi, Chinetti, Tonon, Loro, Visentini, Lualdi, Leali, Battaglin, Santoni) @ 1min 26sec

- Metauro Mobili (van Impe, Rabottini, Vandi, Magrini, Pirard, Zappi, Algeri, Groppo) @ 1min 35sec

- Alfa Lum (Petito, Marino Lejarreta, Ismaël Lejarreta, Maccali, Wilson, Aliverti, Angelucci) @ 1min 53sec

- Vivi-Benotto (Chioccioli, Braun, Salvetti, Viero, Landoni, Bonzi, Donadio, Zuanel, Passuello) @ 2min 10sec

- Europ Decor-Dries (Hoste, Govaerts, Sergeant, Nevens, Sommers, Bogaert, Jacobs) @ 2min 19sec

GC after Stage 1:

- Tommy Prim: 1hr 13min 54sec

- Ennio Vanotti, Alf Segersall, Alessandro Paganessi, Silvano Contini, Sergio Parsani, Valerio Piva

Saturday, May 14: Stage 2, Mantova - Lido di Spina, 192 km

- Guido Bontempi: 5hr 13min 54sec

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Frits Pirard

- Stefan Mutter

- Robert Dill-Bundi

- Harald Maier s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Urs Freuler: 6hr 29min 2sec

- Tommy Prim, Valerio Piva, Sergio Parsani, Ennio Vanotti, Silvano Contini, Alf Sergersall, Alessandro Paganessi @ 10sec

- Paolo Rosola @ 15sec

Sunday, May 15: Stage 3, Comacchio - Fano, 148 km

- Paolo Rosola: 3hr 29min 16sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Gianmarco Saccani s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

- Dietrich Thurau s.t.

- Pierino Ghibaudo s.t.

- Pierangelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Sergio Santimaria s.t.

- Silvano Contini s.t.

- Ricardo Magrini s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Paolo Rosola: 9hr 58min 3sec

- Pierino Gavazzi @ 15sec

- Sergio Parsani, Silvano Contini @ 25sec

- Urs Freuler, Tommy Prim, Ennio Vanotti, Alf Sergersall @ 42sec

- Alessandro Paganessi @ 52sec

Monday, May 16: Stage 4, Pesaro - Todi, 187 km

![]() Major ascent: Cascia Morella

Major ascent: Cascia Morella

- Giuseppe Saronni: 5hr 19min 0sec

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Michael Wilson s.t.

- Mario Beccia s.t.

- Stefan Mutter @ 3sec

- Ricardo Magrini s.t.

- Jean-François Rodriguez@ 5sec

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Lucien van Impe s.t.

- Eduardo Chozas s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Paolo Rosola: 16hr 17min 21sec

- Silvano Contini @ 12sec

- Tommy Prim @ 39sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 42sec

- Giuseppe Saronni, Moreno Argentin @ 44sec

- Wladimiro Panizza, Dietrich Thurau, Valerio Piva @ 49sec

- Alessandro Paganessi @ 52sec

Tuesday, May 17: Stage 5, Terni - Vasto, 269 km

![]() Major ascent: Corno

Major ascent: Corno

- Edoardo Chozas: 6hr 15min 25sec

- Vittorio Algeri @ 21sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 21sec

- Francio Chioccioli s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli s.t.

- Emanuele Bombini s.t.

- Harald Maier s.t.

- Jean-François Rodriguez s.t.

- Marino Lejaretta s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- Silvano Contini: 21hr 33min 22sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 22sec

- Tommy Prim @ 27sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 30sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 37sec

- Dietrich Thurau, Alessandro Paganessi @ 40sec

- Francesco Moser, Fabrizio Verza @ 47sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 50sec

Wednesday May 18: Stage 6, Vasto - Campitello Matese, 145 km

![]() Major ascent: Campitello Matese

Major ascent: Campitello Matese

- Alberto Fernandez: 3hr 50min 7sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 23sec

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

- Lucien van Impe s.t.

- Faustino Ruperez s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Mario Beccia s.t.

- Jostein Wilmann s.t.

- Dietrich Thurau s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Silvano Contini: 25hr 23min 52sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 2sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 37sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 40sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 50sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 59sec

- Edoardo Chozas @ 1min 6sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 10sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 16sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 17sec

Thursday, May 19: Stage 7, Campitello Matese - Salerno, 216 km

![]() Major ascents: Faggio, Acerno

Major ascents: Faggio, Acerno

- Moreno Argentin: 5hr 57min 20sec

- Emanuele Bombini @ 1sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 16sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Fons de Wolf s.t.

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Flavio Zappi s.t.

- Luc Govaerts s.t.

GC after stage 7:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 31hr 21min 12sec

- Silvano Contini @ 8sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 45sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 48sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 58sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 7sec

- Edoardo Chozas @ 1min 14sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 18sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 24sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 25sec

Friday, May 20: Stage 8, Salerno - Terracina, 212 km

- Guido Bontempi: 5hr 42min 11sec

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Moreno Agentin s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Jan Bogaert s.t.

- Claudio Girlanda s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 37hr 3min 31sec

- Silvano Contini @ 8sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 45sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 48sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 58sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 7sec

- Edoardo Chozas @ 1min 14sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 18sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 24sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 25sec

Saturday, May 21: Stage 9, Terracina - Montefiascone, 225 km

![]() Major ascent: Poggio Nibbio

Major ascent: Poggio Nibbio

- Riccardo Magrini: 5hr 50min 57sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 3sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 9sec

- Vittorio Algeri s.t.

- Roberto Visentini @ 11sec

- Mario Beccia s.t.

- Simone Fraccaro @ 14sec

- Patrick Bonnet s.t.

- Graham Jones s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 42hr 54min 42sec

- Silvao Contini @ 8sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 45sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 47sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 48sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 58sec

- Gimabattista Baronchelli @ 1min 7sec

- Edoardo Chozas @ 1min 14sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 22sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 24sec

Sunday, May 22: Stage 10, Montefiascone - Bibbiena, 232 km

![]() Major ascents: Monte Amiata, Radicofani

Major ascents: Monte Amiata, Radicofani

- Palmiro Masciarelli: 6hr 0min 53sec

- Siegfried Hekimi s.t.

- Patrick Bonnet @ 1min 28sec

- Fulvio Bertacco @ 1min 33sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 4min 44sec

- Salvatore Maccali s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Jean-René Bernaudeau s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 49hr 0min 19sec

- Silvano Contini @ 8sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 45sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 47sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 48sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 58sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 7sec

- Edoardo Chozas @ 1min 14sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 22sec

- Fabirzio Verza @ 1min 24sec

Monday, May 23: Stage 11, Bibbiena - Marina di Pietrasanta, 202 km

![]() Major ascents: Consuma, Capezzano

Major ascents: Consuma, Capezzano

- Lucien van Impe: 5hr 36min 25sec

- Pedro Munoz @ 1sec

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Roberto Visentini s.t.

- Moreno Argentin @ 7sec

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 8sec

- Jean-René Bernaudeau s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Alfio Vandi s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 54hr 36min 52sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 30sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 45sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 48sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 52sec

- Silvano Contini @ 56sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 58sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @1 min 7sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1mn 10sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 24sec

Tuesday, May 24: Rest Day (giorno di riposo)

Wednesday, May 25: Stage 12, Marina di Pietrasanta - Reggio Emilia, 180 km

![]() Major ascent: Cerreto

Major ascent: Cerreto

- Alf Segersall: 4hr 24min 10sec

- Giuseppe Saronni 2 22sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Pierangelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Fons de Wolf s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 59hr 1min 4sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 50sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 1min 5sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 1min 8sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 1min 12sec

- Silvano Contini @ 1min 16sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 18sec

- Giambattista Bronchelli 2 1min 27sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 30sec

- Fabrizio Verza @ 1min 44sec

Thursday, May 26: Stage 13, Reggio Emilia - Parma 38 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Giuseppe Saronni: 48min 49sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 30sec

- Urs Freuler @ 1min 1sec

- Gregor Braun @ 1min 9sec

- Tommy Prim s.t.

- Dietrich Thurau @ 1min 28sec

- Silvano Contini @ 1min 52sec

- Daniel Gisiger @ 2min 0sec

- Claudio Torelli @ 2min 1sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 2min 4sec

GC after stage 13:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 59hr 49min 53sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 20sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 2min 34sec

- Silvano Contini @ 3min 8sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 3min 16sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 3min 36sec

- Tommy Prim @ 4min 0sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 4min 8sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 4min 24sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 4min 38sec

Friday, May 27: Stage 14, Parma - Savona, 243 km

![]() Major ascent: Cento Croci

Major ascent: Cento Croci

- Gregor Braun: 5hr 56min 20sec

- Urs Freuler @ 13sec

- Pierangelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Alfredo Chinetti s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Davide Cassani s.t.

- Patrick Bonnet s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 65hr 46min 20sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 20sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 2min 34sec

- Silvano Contini @ 3min 8sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 3min 16sec

- Wladimrio Panizza @ 3min 36sec

- Tommy Prim @ 4min 0sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 4min 6sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 4min 24sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 4min 36sec

Saturday, May 28: Stage 15, Savona - Orta, 219 km

![]() Major ascent: Giovo

Major ascent: Giovo

- Paolo Rosola: 6hr 7min 3sec

- Gerhard Zadrobilek s.t.

- Silvano Contini s.t.

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Vittorio Algeri s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 71hr 53min 29sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 20sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 2min 34sec

- Silvano Contini 2min 58sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 3min 16sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 3min 30sec

- Tommy Prim @ 4min 0sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 4min 8sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 4min 24sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 4min 38sec

Sunday, May 29: Stage 16A, Orta - Milano, 110 km

- Frank Hoste: 2hr 34min 26sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Claudio Girlanda s.t.

- Emanuele Bombini s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Peter Kehl s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Frits Priard s.t.

- Marc Van Den Brande s.t.

GC after Stage 16A

- Giuseppe Saronni

Sunday, May 29: Stage 16B, Milano - Bergamo, 100 km

![]() Major ascent: Roncola

Major ascent: Roncola

- Giuseppe Saronni: 2hr 16min 49sec

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Tommy Prim s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Emanuele Bombini s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

- Jean-René Bernaudeau s.t.

- Alessandro Paganessi s.t.

- Harald Maier s.t.

GC after Stage 16B:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 76hr 44min 14sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 50sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 3min 4sec

- Silvano Contini @ 3min 28sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 3min 46sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 4min 6sec

- Tommy Prim @ 4min 25sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 4min 38sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 4min 54sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 5min 8sec

Monday, May 30: Stage 17, Bergamo - San Fermo, 91 km

![]() Major ascent: San Fermo

Major ascent: San Fermo

- Alberto Fernandez: 2hr 12min 19sec

- Luicien van Impe @ 17sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 19sec

- Mario Beccia @ 25sec

- Pedro Munoz @ 30sec

- Fuastino Ruperez @ 34sec

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Alessandro Paganessi @ 1min 13sec

- Silvano Contini @ 1min 18sec

- Miro Poloncic @ 1min 29sec

GC after Stage 17:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 78hr 57min 7sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 25sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 3min 9sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 3min 34sec

- Silvano Contini @ 4min 10sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 5min 4sec

- Tommy Prim @ 5min 55sec

- Mario Beccia @ 6min 2sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 6min 13sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 6min 17sec

Tuesday, May 31: Stage 18, Sarnico - Vicenza, 178 km

![]() Major ascent: San Eusebio

Major ascent: San Eusebio

- Paolo Rosola: 4hr 32min 54sec

- Pierangelo Bincoletto @ 1sec

- Silvano Riccò s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Giuliano Pavanello s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Stefan Mutter s.t.

- Luigi Trevellin s.t.

- Frits Priard s.t.

- Marc Van den Brande s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 83hr 30min 2sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 25sec

- Lcucien van Impe @ 3min 9sec

- Juan Feranandez @ 3min 34sec

- Silvano Contini @ 4min 10sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 5min 4sec

- Tommy prim @ 5min 55sec

- Mario Beccia @ 6min 2sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 6min 13sec

- Marino Lejarrreta @ 6min 17sec

Wednesday, June 1: Rest Day (giorno di riposo)

Thursday, June 2: Stage 19. Vicenza - Selva di Val Gardena, 224 km

![]() Major ascent: Selva di Val Gardena

Major ascent: Selva di Val Gardena

- Mario Beccia: 5hr 57min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Emanuele Bombini @ 17sec

- Eduardo Chozas s.t.

- Eddy Schepers s.t.

- Juan Fernandez s.t.

- Jean-René Bernaudeau s.t.

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

- Roberto Visentini s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 89hr 27min 28sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 25sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 3min 34sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 5min 3sec

- Mario Beccia @ 5min 13sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 38sec

- WLadimiro Panizza @ 6min 21sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 6min 53sec

- Eduardo Chozas @ 7min 28sec

- Faustino Ruperez @ 7min 52sec

Friday, June 3: Stage 20, Selva di Val Gardena - Arabba, 169 km

![]() Major ascents: Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Campolongo

Major ascents: Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Campolongo

- Alessandro Paganessi: 4hr 29min 52sec

- Mario Beccia @ 2min 3sec

- Jean-René Bernaudeau @ 2min 5sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 2min 16sec

- Faustino Ruperez s.t.

- Roberto Visentini @ 2min 26sec

- Eduardo Chozas s.t.

- Luciano Loro s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Pedro Munoz s.t.

GC after Stage 20:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 94hr 0min 15sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 56sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 2min 50sec

- Mario Beccia @ 4min 1sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 9sec

- Eduardo Chozas @ 6min 59sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 7min 10sec

- Faustino Ruperez @ 7min 13sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 8min 16sec

- Pedro Munoz @ 8min 58sec

Saturday, June 4: Stage 21, Arabba - Gorizia, 232 km

- Moreno Argentin: 5hr 54min 41sec

- Frank Hoste @ 2sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Dante Morandi s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Jörg Bruggmann s.t.

- Nazzareno Berto s.t.

- Piernangelo Bincoletto s.t.

- Frits Pirard s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Giuseppe Saronni: 99hr 54min 58sec

- Roberto Visentini @ 1min 56sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 2min 59sec

- Mario Beccia @ 4min 1sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 9sec

- Eduardo Chozas @ 6min 59sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 7min 10sec

- Faustino Ruperez @ 7min 13sec

- Lucien van Impe @ 8min 16sec

- Pedro Munoz @ 8min 58sec

Sunday, June 5: 22nd and Final Stage, Gorizia - Udine 40 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Roberto Visentini: 49min 43sec

- Daniel Gisiger @ 32sec

- Giuseppe Saronni @ 49sec

- Urs Freuler @ 1min 0sec

- Marc Somers @ 1min 5sec

- Dietrich Thurau @ 1min 23sec

- Frits Pirard @ 1min 38sec

- Juan Fernandez @ 1min 39sec

- Czeslaw Lang @ 1min 40sec

- Gregor Braun, Faustino Ruperez @ 2min 0sec

The Story of the 1983 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

The 1983 edition went easy on the climbing (and the rouleurs), with only one hard day in the mountains, stage twenty out of the twenty-two scheduled. It was assumed that the route had been crafted with both Giuseppe Saronni’s superb sprinting and tolerable ascending skills and Moser’s big gear mashing and poor climbing in mind. Of the 162 riders who showed up in Brescia on May 12 to begin the race for the Pink Jersey, there were only a few true contenders. The odds-on favorite had to be Giuseppe Saronni, the reigning World Road Champion. Since winning the Rainbow Jersey in Goodwood, England in late 1982, he had gone on to win the Tour of Lombardy, Milan–San Remo and had come in second in Liège–Bastogne–Liège.

Roberto Visentini (who replaced Battaglin as the leader of the Inoxpran team, which was riding Battaglin bikes) and Tommy Prim were also high on the list of possible winners. Prim was saddled with his Swedish nationality, so far a handicap on the Bianchi team. Bianchi, an Italian company wanting to sell oodles of bikes in Italy, had preferred an Italian winner. Ironically, Bianchi is now owned by Grimaldi Industri, a Swedish company.

The Giro was supposed to start with a prologue individual time trial. The riders were suited up and the first man to ride, Jesus Ibañez, was on his bike. But then he had to wait, and wait some more. Striking workers were blocking the road and the police, not wanting to make a bad situation worse, didn’t interfere. The prologue was cancelled.

The crowd waits for the time trial that wasn't run

They moved on to the next stage, a 70-kilometer team time trial going from Brescia to Mantua, which Prim’s Bianchi squad won. And, surprisingly, Bianchi’s director Ferretti had Prim cross the line first, letting the Swede become the first 1982 maglia rosa. The team’s times didn’t count towards the General Classification except for the time bonuses given to the top three teams, putting Saronni, whose Del Tongo team came in fifth, in thirty-first place at 40 seconds.

The next two stages let the sprinters show their speed. Fifteen kilometers before the end of the third stage there was a crash, taking about twenty riders down. Trapped behind the pile-up were Saronni and Moser. Capitalizing on the situation, Baronchelli and Battaglin hammered all the way to the finish line in Fano, beating the unlucky riders by 27 seconds.

The first hint as to who could climb came in stage four, with its six-kilometer ascent to Todi in Umbria. Lucien van Impe had driven the field hard up an earlier, more modest climb and had split the pack. Saronni out-sprinted the surviving 40 riders. By virtue of sprint time bonuses, Paolo Rosola was leader and Saronni was in fifth place.

The next day Saronni generated near panic when he got into a fast moving break on the road to Vasto because many of the big names had missed the move, including Prim, Moser and Baronchelli. Ferretti showed his intentions when he made Contini slow the break while Prim didn’t do any work helping the pack chase the escapees. The break was caught after more than 100 kilometers of pursuit, mostly because of Moser’s long, hard stints at the front of the chase. Then another break went and this time it was Saronni and his teammate Didi Thurau who did most of the work of shutting down the escape. But Eduardo Chozas had slipped away from the break to win the stage, keeping just 21 seconds of what had been a four-minute lead, plus a 30-second time bonus, after 60 kilometers of hard work.

Rosola had missed the important moves and Contini, despite Ferretti’s favoring Prim, was the maglia rosa.

Stage six ended with the first hilltop finish of the year. Spanish rider Alberto Fernández made a series of in-the-saddle attacks and after the third, he was clear with six kilometers to go to the top of Campitello Matese. Saronni, with Franco Chioccioli and van Impe right with him, finished 23 seconds behind. The day was a disaster for Prim and Moser, who both lost more than two minutes.

The race continued heading for the western side of Italy with another day in the Apennines. There were two rated climbs that allowed van Impe to get clear with Marino Lejarreta and Jostein Wilmann. With only a few kilometers to go into Salerno, all three crashed, allowing a big sprint finish to settle things. Moreno Argentin won the stage, but Saronni’s third place gave him enough bonus seconds to take the lead and don his twentieth Pink Jersey.

After stage seven and a week of racing, the General Classification stood thus:

1. Giuseppe Saronni

2. Silvano Contini @ 8 seconds

3. Wladimiro Panizza @ 45 seconds

4. Didi Thurau @ 48 seconds

5. Giovanni Battaglin @ 58 seconds

As the race turned northward, the next few stages didn’t affect the standings, with Saronni keeping his slim lead. Visentini seemed to be the only rider who consistently challenged Saronni. He got into a good-looking break in the hilly stage eleven in western coastal Tuscany, but the move, less one rider, was reeled in with a few kilometers to go. It was 37-year-old Lucien van Impe who surprised everyone when he shot off the front of the dying break, winning the stage seven seconds ahead of the surging pack.

Saronni blitzed the Parma time trial, beating Visentini, also an excellent man against the clock, by 30 seconds. Moreover, by turning in such a good time, Saronni delivered a serious setback to the specialist climbers who were looking forward to the coming high mountain stages, but who now had an imposing time gap to close. Van Impe lost over two minutes.

The last stage of the second week took the riders out of Emilia-Romagna and into Liguria and the coastal road used by the Milan–San Remo race. The day’s riding was perky enough to have Saronni put his Del Tongo team (most notably Thurau) at the front of the pack to bring a few wayward riders back to the peloton. Saronni’s position was vastly improved because Battaglin was suffering from stomach problems and lost a half-hour.

After fourteen stages and two weeks of racing, the high mountains were only two stages away. The General Classification stood thus:

1. Giuseppe Saronni

2. Roberto Visentini @ 2 minutes 20 seconds

3. Didi Thurau @ 2 minutes 34 seconds

4. Silvano Contini @ 3 minutes 8 seconds

5. Lucien van Impe @ 3 minutes 16 seconds

Battaglin, sick and well down on the Classification, abandoned at the start of stage sixteen.

Stage 16b went over the Roncola Pass on the way to Bergamo. Van Impe did what van Impe did best: he attacked on the climb, but Saronni was able to stay with him while Contini was dropped. They came together on the descent for the nearly inevitable Saronni sprint win. So far, at no point in this Giro had Saronni been in trouble.

The next day was a short 91-kilometer stage with a hilltop finish on the Colle San Fermo. Once the pack hit the 1,067-meter-high mountain, van Impe was off the front again. Saronni kept him in sight while Alberto Fernández caught and dropped the Belgian. Saronni tried to hold a surging Visentini’s wheel but couldn’t. The damage was manageable, as there was only 15 seconds between them.

After Paolo Rosola won the sprint into Vicenza for his third stage victory, there was another rest day. There were two mountain stages and a time trial left to affect the outcome.

Stage nineteen up to Selva di Val Gardena, into the heart of the Dolomites, could have been a challenging climbing stage. It wasn’t. The organizers looked for and found the easiest gradients into town. There was a climb at the end but van Impe didn’t participate in the final rush for the line. Hoping to lighten his load for the climb, he had tossed his musette with food and later came down with the hunger knock. It was a strange error for one of the most experienced and finest riders ever to turn a crank. His teammate Alfio Vandi caught up to him and revived van Impe with his own food. The Belgian was able to repair a lot of the damage, but he wasn’t able to attack on a day that he had planned to gain real time. Mario Beccia led Lejarreta across the finish line and Saronni and Visentini finished just 17 seconds behind them.

Stage twenty was the only real day in the mountains, a race on the sinuous and beautiful road around the Gruppo Sella massif with ascents of the Campolongo, Pordoi, Sella, and Gardena passes, and then up the Campolongo again. Alessandro Paganesi rode an epic race by escaping on the first ascent of the Campolongo and holding his lead all the way to the end. It was heroic, but did not affect the outcome of the Giro.

What did matter was Visentini’s attack on the Pordoi, the Cima Coppi for the 1983 edition. Saronni didn’t jump to close the gap, continuing instead to ride at his own measured pace, keeping Visentini in sight. By the top of the Pordoi, Visentini was a minute ahead of Saronni. Over the Sella, the gap remained unchanged. As they climbed the Gardena, Visentini appeared to be weakening and at the top, the gap was down to 40 seconds. Both riders were tiring. After the final ascent of the Campolongo they flew down the hill to Arabba and at the end of this titanic pursuit through the Dolomites, Visentini had managed to hold off Saronni by 29 seconds.

The flat penultimate stage could have given Saronni and his wonderful ability to sprint a chance to gain to bonus seconds, but others beat him, leaving him with a two-minute cushion on a man most thought to be the superior time trialist.

“Expect a surprise,” Visentini predicted.

With only the final 40-kilometer time trial stage left, the General Classification looked like this:

1. Giuseppe Saronni

2. Roberto Visentini @ 1 minute 56 seconds

3. Alberto Fernández @ 2 minutes 50 seconds

4. Mario Beccia @ 4 minutes 1 second

5. Marino Lejarreta @ 5 minutes 9 seconds

Looking stylish and elegant on his bike, Visentini did win the stage, but took only 49 seconds out of Saronni, not nearly enough to wrest the Pink Jersey.

When I visited Italy that fall for the Milan bike show I heard unbelievable stories about an attempt to sabotage Saronni’s time trial ride, but half-doubted them as gossip. It turns out they were true. Visentini rode Battaglin bikes equipped with FIR rims and the owner of FIR, Giovanni Arrigoni, was a little too eager for a Giro victory on his equipment. Signor Arrigoni traveled to the hotel in Gorizia where Saronni’s Del Tongo team was spending the night before the time trial and tried to bribe two of staff to put Guttalax, an extremely powerful laxative, in Saronni’s food. Despite the offer of two million lire (about 1,500 US dollars), the alarmed hotel employees called the police and the press and Arrigoni was arrested. Saronni’s food was safe. It was a strange move for a well-liked man whose company was enjoying extraordinary worldwide success in the rim market and who had contracted to have Saronni use his wheels the following season.

Giuseppe Saronni

Final 1983 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo-Colnago) 100 hours 45 minutes 30 seconds

2. Roberto Visentini (Inoxpran-Lumenflon) @ 1 minute 7 seconds

3. Alberto Fernández (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor) @ 3 minutes 40 seconds

4. Mario Beccia (Malvor-Bottecchia) @ 5 minutes 55 seconds

5. Dietrich Thurau (Del Tongo-Colnago) @ 7 minutes 44 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Lucien van Impe (Metauro Mobili-Pinarello): 70 points

2. Alberto Fernández (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor): 43

3. Tie between Marino Lejarreta (Alfa Lum-Olmo) and Pedro Muñoz (Gemeaz Cusin-Zor): 27

Points Competition:

1. Giuseppe Saronni (Del Tongo-Colnago): 223 points

2. Moreno Argentin (Sammontana-Campagnolo): 149

3. Frank Hoste (Maria Pia-Europ Decor-Dries): 139

Visentini complained that his actual riding time was less than Saronni’s and without the time bonuses, he would have won the Giro. Saronni won 3 minutes 20 seconds in bonuses compared to Visentini’s 1 minute 25 seconds. By my arithmetic Visentini rode the 1983 Giro 48 seconds faster. But, them’s the rules Roberto, and that’s how the game is judged.

The 1983 Giro being run over such an easy course, probably the least challenging postwar route to date, was raced at the then record pace of 38.937 kilometers per hour, finally beating 1957’s record 37.488 kilometers per hour held by Gastone Nencini. 1957’s Giro was fast not because the course was easy, but because the competition that year was nothing less than savage.

.