Cycling in Italy, 2005: The Long Good Ride

|

||

All year long I dream about my annual 12 days of riding in Italy. I bore to tears everyone around me. I have reasonably polite friends. As I start talking about my favorite topic they try to feign a courteous interest. Yet, as I blather on, they always seem to be looking at their watches or searching for the nearest door. I can't help myself. This is about bikes and bikes are all I'm good for. If they made bikes illegal I'd be stuck somewhere at an intersection with a squeegee.

As the day to leave for Italy approaches I become a worry-wart. The internet has given those of us with poor mental health a chance to manufacture a whole new set of concerns. I have weather.com bookmarked and check it maniacally. My wife Carol should just unplug my computer. It would save everyone around me a lot of trouble.

Weather for Milan, Tuesday: 6C, 70% chance of rain.

Augh! I keep checking. If I keep looking and hoping maybe the weather will get better. Sort of a corollary to clapping to bring Tinkerbell back to life.

Weather for Milan, Tuesday, 15C, cloudy.

OK, that's better. But still restive, I start checking almost hourly.

Weather for Milan, Tuesday, 6C, 30% chance of rain.

No! I'm going to Sunny Italy where they sing O Sole Mio (Oh, My Sun). Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni stroll the Via Veneto and everyone lives La Dolce Vita. To me that means warm air, bright sun and no rain. I plan to ride in shorts and wave to all the pretty Italian girls who will, in return, all have a kind "ciao" or "salve" for me.

Weather for Milan, Tuesday, 10C, 60% chance of rain.

People around me were beginning to believe I was bipolar. I would look at the forecast and see good weather for the first day in Italy and be happy and content. A few hours later I would find the forecast had changed to rain, turning me glum and quiet. Telling me that there's nothing I can do about it anyway didn't help. Telling me that even if the millennial deluge comes I'll still go out and ride so there's no point in even looking at the weather forecast didn't help. I was in no mood to hear rational talk.

So finally the time has arrived. It's late March and it's time to go cycling in Italy. Each year I pick three cities to spend two or three days in each, riding big, unhurried loops in the mountains. This year we chose Lucca on the western coast of Tuscany, Orvieto in southern Umbria, and Arezzo in northeastern Tuscany.

A Fiat or Renault van holds exactly three bikes and four people and their luggage. My wife Carol and I were fortunate to be joined by our local bike guy Ted Saville of the Camarillo Bike Company and Kyle Schmeer, owner of Cycles BiKyle in Philadelphia.

Like most travelers I detest air travel, especially now that our government has imposed the National Fear State upon a scared yet complacent population. Despite the worst efforts of both my government and the travel industry to make any air trip intolerable my trip turned out to be one of one of those perfect journeys. That doesn't happen very often, but every now and then the gods smile and feel kind. At every opportunity that fate had to cause problems: customs, security, flight connections, it was all as smooth as can be. We exited from customs at Milan and were greeted by Antonio Mondonico and Kyle. Everything was fine there except for one huge problem. Kyle's bike was still in Paris. Kyle and his luggage had made the connection, but the bike was having an extended, unscheduled stay in the City of Light.

It's nice traveling with philosophical, easygoing, amiable people. I'm not sure that people who travel with me have that same luxury. Kyle just shrugged his shoulders, said there was nothing to do except to wait for the bike to show up and get delivered to the hotel. He was right but most people have trouble being calm in the face of adversity. I should try to be like Kyle.

We got to the Mondonico's home and workshop and were met by Antonio's lovely and charming wife, Gabriela. Mauro, his oldest son and my usual riding companion in Italy wasn't there and couldn't ride with us. He was working for RCS Sport (promoter of most of the important Italian pro races) driving the chief race referee at the Tour of Reggio Calabria.

Gabriela anticipated my first and most important request, a big cup of her coffee, the best in the world. Do angels exist in heaven? I don't know. But I do know there is an angel in Concorezzo and her name is Gabriela. After a day-long transatlantic journey a steaming mug of hot coffee with long-separated friends is true joy, a pearl beyond price.

|

||

|

Gabri brings the java. I'm going to be all right. |

||

As Antonio took Ted's bike out of the box and fired it up, Gabri got the spaghetti boiling. Now I'm in heaven.

And my worries about the weather? The sky was blue and the air was warm. Even though the forecast insisted that the chances for rain the next day were good, the beautiful day seemed to shout that all would be well. It couldn't rain when things were this fine.

Tuesday, March 29. In years past we have ridden straight from Mondonico's house up to Como, Bellagio and Lecco. Lecco lies at the base of one of the two lakes that sit just north of Milan. From there we could ride up the narrow road that follows the lake shore and end up in Bellagio, which lies at the apex of the triangle of land that is straddled by the two lakes. In the intervening years traffic has grown too dense to do that ride with safety and enjoyment. Antonio insisted upon driving us to a better starting point, in Oggiano, north of Milano. From there we could ride to the city of Como and up the shore of Lake Como to Bellagio. From there we would head due South, up the climb to the Madonna del Ghisallo and back down to Oggiano.

As we drove, the sky to the east looked a bit unsettled but dry. The sky to west, over Como, looked ever darker. Sprinkles of rain spattered the windshield. The roads were wet. It looked as if the storm were heading west. I thought that we were probably on the trailing edge of the storm and that it would all pass. Self-deception may be the most highly developed capability of the human intellect.

Antonio stopped and let us out of the van. The air was heavy with moisture and an occasional drop fell but it didn't seem to anything to be really concerned about.

As soon as he was on the bike Ted sped off riding as if he were a captured animal just freed from a cage. I could see that this was going to be a long morning. In my youth, not needing any warm-up, I used to torture other riders by taking off from the gun. Those days are long gone and I now need at least ten miles of medium effort before my legs stop hurting and can actually turn the pedals with any force. I am being repaid for the sins of my youth. The karmic wheel has turned.

As we rode west and came closer to Como the drops became light rain showers. The air got colder. We knew that since Antonio with Kyle were following us in the van we could bail from the ride at any time. Strange. When a ride like this is completely voluntary the compulsion to complete it becomes far stronger. One feels as if the challenge has to be met and overcome. We are such social animals that with good company a ride in the cold rain can actually be enjoyable.

We did the long, curving descent among the cars and trucks into Como. That was cold. Ted and I misunderstood Antonio's directions and wandered a bit in the city, getting even colder as the rain came down ever harder. At last we found the narrow little strip of asphalt that is the main road that heads north to Bellagio.

This is one of the most beautiful roads in the world. The lake, today shrouded in mist, is in a valley that has been lined with homes for almost all time. The road rises and falls constantly. Even though the passage is narrow the drivers of both trucks and cars are invariably courteous and give cyclists plenty of room. The rain came down ever harder. Now it was pouring. We were a tad underdressed. We passed through a long tunnel and for a little while avoided the rain. With that small respite we were able get warmed up again and continue our excursion.

At Bellagio, we saw the signs for the Madonna del Ghisallo and the city of Erba. This was our cutoff. Normally we would want to go to the shore and admire the view, one of the finest anywhere. But in the cold rain we were right on the edge of just being warm enough to ride, so up the hill we went.

This ascent is several kilometers long with a short stretch of road that reaches a fifteen percent gradient. Normally I can handle a climb that stiff with my 23 without too much trouble. Not this day. Having been off the bike for a few days, my legs were blocky and weak. This was about as hard a climb as I had ever done. But with two friends in the van behind watching me and Ted a bit up the road, I just couldn't quit. I just couldn't. I dug as deeply as I could, stood up and got the bike up the hill. The road sign said eight switchbacks ahead. It seemed like eighty. Ted is a superb climber so I watched him disappear up the road. I consoled myself that he was only a youthful forty years old. Just a kid. Probably not even shaving yet.

|

|||

|

Ted flies up the steep switchbacks with apparant ease. Has he no shame? |

|||

Up and up we went, into the cloudy mist. At the top of the mountain stands the famous Madonna del Ghisallo church and museum which is filled with some of the most famous bikes and cycling souvenirs in the world. We had planned on stopping there before doing the descent. Not today. A visit to an unheated church was not in the cards. And today we could not do the descent. It would be just too cold. We put our cold bodies and bikes in the warm van and headed back to the barn. Don't be mistaken. It was a pleasurable, fun and good ride and a fine adventure that ended at just the right time. I'm also really glad than Antonio had the van right there and that he had been running the heater.

Antonio tossed us off at our hotel where we hoped to find Kyle's bike, delivered at the earliest possible moment by the kind people at Alitalia.

No bike! Drat! Kyle stayed sunny and smiling without the slightest touch of grumpiness.

After a good, hot shower we headed back to the Mondonicos. Antonio had cleaned our bikes. What a nice man. There is no hospitality like Mondonico hospitality. Hoping that Kyle's bike might yet get delivered today we wanted to prolong our stay here as long as possible before heading down to our next city, Lucca. We went to the local sandwich shop for a bite.

The nice lady asked us what we wanted. Here we managed to turn a simple question into an insurmountable problem. The lady had no pre-made sandwiches so each one would be custom made. No one had any really strong feelings about what to have and yet each one of us had some vague idea of what would be good. Since the choices of filling, bread and dressings made an almost limitless number of permutations, the orders for the four sandwiches kept coming at her and changing every 10 seconds. We would never eat. We were just stupid-tired-hungry-jet-lagged enough to be incapable of this simple task. Finally we told her to make four good sandwiches and left it there.

She did just that and they were terrific.

We got back to Mondonicos to finish packing. Still no bike for Kyle. Well, the airline had our itinerary so we moved on to Lucca in northern Tuscany.

|

||

|

Bikes cleaned, we're ready to head for Orvieto. From the right, standing: Ted (holding his beautiful Torelli 20th Anniversary bike), Antonio Mondonico, Chairman Bill, Kyle. In front, Man's Best Friend and Giuseppe Mondonico. |

||

Wednesday, March 30.

"Mr. Guerciotti has been by but he must park his car," the desk clerk told me.

So, Paolo made it. Yet I wondered. Had I done him a favor by asking him to come riding with us? The rain forecast for today was a 60% chance of rain.

"But," said the clerk, "That means that there is a 40% chance that it will not rain." Nice attitude. I am not one who thinks that the glass is half empty. I think someone probably stole my water.

The sky got ever bluer and the air kept getting warmer. This could be the day I was looking for. And still no bike for Kyle.

We headed on a north, northwest direction out of Lucca for the Apuan Alps. We got a late start so that my planned, big 135 kilometer loop wasn't possible. We would head up toward Garafagnana until time ran out and then head back.

For the first 20 kilometers the road north out of Lucca is gentle with a one or two percent gradient. Paolo took the point and pounded his big gear at 18 to 20 miles an hour. Another tough start of the day for me. Someone upstairs is laughing at me.

We just hauled all the way up to the little town of Nocchi. We found ourselves faced with a beautiful vista with a valley below us filled with pretty Italian villages. I would post a picture here but I didn't take my camera this day, fearing the rain.

The descending switchback was gentle and didn't even challenge my poor cornering skills. Since Paolo has a vacation home in nearby Viareggio these were his training roads. We didn't have to ask for directions. We just shut up, sat down and hung on.

After about 30 kilometers of riding north, just inland up the coast, we passed through Seravezza. The famous marble quarries of Carrara are just 20 kilometers to the north of us. As we rode we passed work-yard after work-yard filled with marble quarried from the hills around us awaiting cutting and finishing. The mills that specialize in cutting marble also lined the road. The unfortunate consequence of this was that the roads were covered in marble dust and water that dripped from the trucks carrying the newly cut stone. This made a dangerous, slippery slurry that could be treacherous for the unwary aggressive rider.

After Seravezza, the road climbs up into the Apuan Alps. The way isn't very steep. We were able to manage it easily in a 21. I keep my heartrate under 170 on these trips so that I don't run out of legs and lungs before I run out of vacation. This climb needed only about 155 beats per minute (my anaerobic threshold is about 176) to ride at a moderate pace.

Just before Culaccio where we had climbed to 800 meters, we had to turn back.

Now the wind was at our face. No wonder this climb was so easy with that nifty tailwind pushing us up the hill.

Respecting the tenuous hold our tires had on the slippery road, we descended at a moderate pace. From Seravezza we started to really push it. We wanted to be back by a little after noon so that we could shower before the restaurants closed at two.

At Pietrasanta, we did a short detour. Aliveti, a pro from the 1980's, had a bicycle shop in town and Paolo wanted to stop in and say hi to an old friend. It was a beautiful, well organized shop and Signor Aliveti was a very nice man. He told us that if Kyle's bike didn't show up that we should come by and borrow one from him.

An historical note about Pietrasanta. The marble for Michelangeloa's Pieta and other early masterpieces did come from the Carrara quarries to the north. But later his Medici patrons had him use the marble from this area in an effort to open new quarries that would compete with Carrara. It was Pietrasanta that controlled the territory that held the marble of these new quarries and as what seems to be true about all Renaissance history, friction between the two cities started and grew.

We clicked into our pedals and finished the ride back to Lucca. A very pleasant and enjoyable ride of exactly 100 kilometers.

The legs were coming back.

Lucca is such a civilized city. Bikes are everywhere. The ancient city walls are competely intact. The thoughtful people of Lucca have turned the top of the wall into a beautiful bike path lined with trees.

|

||

|

Up on the city walls of Lucca. You can see how thick old city walls had to be in order to repel invasions. Kyle photo |

||

Having been set up by the very orderly Romans, many of the streets are laid out in a grid with the the intersections at right angles. Any traveler to Italy knows how rare this is.

This is a wonderful city that is a joy to just wander around. There are superb churches done in the distinctive version of Italian Gothic that the artists of nearby Pisa developed. They are in great shape and do command the attention of any tourist. Yet, the real joy of this city are the almost car-free steets lined with a nice mix of old buildings and modern shop fronts.

|

||

|

Lucca: Bikes everywhere |

||

After an afternoon of mindless meandering around the town we were met by a nearly jubilant hotel staff.

"The bike is here!!"

Kyle's bike had finally arrived. Earlier Kyle had managed to get past the voice-mail recordings at Alitalia (thanks to both out travel agent, Judy Van Dyke at Camarillo Travel, and Kyle's wife, Susan) and been told that his bike had been flown to Pisa, just 20 kilometers from Lucca. Kyle had been given this promise:

"I guarantee that you will get your bike today. Absolutely. I hope."

That's about as certain as we could hope for. And there it was, Kyle's bike, still packed in its travel box in the hotel lobby.

Thursday, March 31: This was a transfer day. We had to get in our ride and shower and vacate the room before noon. Normally the Hotel La Luna, where we were staying, has an 11:00 AM checkout. But, being kind and understanding our desire to get in a decent ride, they let us push the checkout to noon. Thanks!

It was cool but clear as we set out. At the first opportunity we took the wrong turn in town and ended up as far from the correct exit as possible. Since Lucca still has it's solid 40-foot thick city walls intact with a bike path on top, we just rode up onto the wall and started to head for the desired city gate.

"Wait," Kyle said, "You're going the wrong way."

So we did a 180. Nope, that was also the wrong way. We found ourselves doing a 270 degree tour of the circumference of the city. Oh well, the walls and the morning were pretty. We did come to Italy to ride our bikes without any particular destination or purpose. After a little more trouble we finally ended up on the right road, heading almost due south for Pisa.

We crested the mountain that sits between Lucca and Pisa before the descending onto the Arno River plain. I was hoping that Ted and Kyle would be greeted by the sight of Pisa a short way off in the distance with the Leaning Tower, Cathedral and Baptistry's white marble glistening in the sun. Not this morning. Pisa was shrouded with morning fog. As we did the switchback down the hill into San Giuliano the roads were still wet. Normally this is a rocket-fast descent with nice wide turns. None of us wanted to decorate a Scania truck's radiator so we took it with a bit of care. The road from Lucca, Route 12, goes right by the Piazza dei Miracoli with the great monuments. It was easy to just ride into Pisa and pull right up next to the tower.

|

|

|

Just head down Route 12 until you come to the Leaning Tower of Pisa... |

|

Last time I was there the tower was covered with apparatus to keep it from leaning further. There was a great fear that the tower would continue to lean ever further and eventually fall. Weights and cables had been attached, hoping to save the ancient building. Now with underground counterweights installed all of those appurtenances had been removed. It stood there, leaning, but standing again free of any obstructions. It was early, so the hordes of day-tourists that come to Pisa were just starting to show up.

We scooted back north up the 12, the way we came in to San Giuliano Terme so that we could head east without going through the awful Pisan traffic. The fog was burning off and the day was turning perfect. At Calcinaia, just a bit north of the Arno, we turned due north for Lucca.

Here, the hills weren't really hills. They just rolled gently up and down, never really forcing us to leave our big rings. We had started off just a little late so were were hustling to get back before our checkout deadline.

We pulled into the hotel just a few minutes before twelve. We showered and ran downstairs with the bags. We freed up the rooms just 10 minutes late. I always want to get the rooms emptied as agreed not so much because I want the hotel happy, but that is a consideration since a deal is a deal. More importantly the chambermaids are generally housewives who want to get their morning work done and get home to have lunch with their families. I don't like the idea of ruining someone's lunch because I didn't start on time or figured I could ride further than was actually possible.

We loaded the van and headed almost due south to the little burg of Orvieto.

As we drove, the heavens opened up with spotty, but really hard rain. Better to get it while in a van than on the bike.

Orvieto sits high atop a tall tufa mound. I have always liked coming here because, first of all, the cycling in the area is without peer. There are lots of lonely roads with very little traffic. It may be the best city for cycling in Italy.

|

|||

|

The view of the countryside from Orvieto |

|||

In 1999 we visited in Orvieto, staying in the Duomo hotel which is hard by the cathedral. Back then the current owners had just bought it. It was an old, dark hole, but the owners were very helpful and friendly. So even though the beds were worn out and the rooms had a feel of decay we thoroughly enjoyed our visit.

I was not prepared for what confronted us when we walked in the lobby. It was as if someone had just set off a bomb in the hotel, cleared out the rubble and started anew. The place was not only completely renovated, it was done with a fine artistic touch that made it a warm and inviting home for a traveler. And yes, the same owners were just as warm and friendly as before.

After we checked in and stowed the van, the manager (and owner) told us that breakfast was at 7:30 AM. I asked him if we could have it at 7:15 as we had agreed when I made the reservation. He said, of course we could.

Friday, April 1: I went downstairs a little after 6:30 in the morning to be greeted by a kindly night porter. He insisted upon making me coffee and seeing that I was completely content. A few minutes later Kyle and Ted joined us. We sat down in the breakfast room about seven and started to eat some of the food that was already set out on the buffet table. The owner's wife saw us and told us that breakfast was at 7:30 and turned out the lights in the room. She left and the night porter went back and turned them on.

The wife came back and turned them off and left.

The night porter came back and turned them on.

I guess she gave up trying to enforce a rule that had no point in that the food was out and coffee had been made for us.

Full of food, we took off for our first stop, Bolsena. That meant a sharp descent off the Orvieto mountain and then a 14 kilometer climb before descending down to Bolsena, sitting on the shore of giant Lake Bolsena. As we crested the hill, most of the far shore was still in fog and a light breeze was starting to blow.

In Bolsena we turned south to do a circumnavigation of the lake. We had a good tailwind and I knew we were going to pay dearly for this pleasure. After about six kilometers the road began to rise and then started to actually climb. We dropped the chains into the small rings. It wasn't a grunt. We were spinning our 21's almost continually to our first stop on the lake, Montefiascone.

A quick check of the map and a couple of questions to the locals and we were headed west on a nice, fast downhill. There was almost no traffic and the lake with its islands in the center was now beautiful in the clear air. The fog had burned off and the hills, covered with olives, nut trees and vineyards and dotted with little cities, were just beautiful.

As we turned ever northward in our circle, the wind got stronger. After the little town of Capodimonte we lost our paved road. We rode on a potholed dirt rode for about seven kilometers with a stiff wind hitting our left side.

|

||

|

Ted gets out of the saddle to keep the bike going against the wind on the dirt road on the shore of Lake Bolsena. |

||

We reached the northern apex of the lake and had to decide if we had time to head up into the Volsini mountains. No, with an average speed of just 14 miles an hour we had to head straight back to Bolsena and then to Orvieto.

Now we had a hard head wind. I was really happy that I had invited Ted. He's as strong as a horse and about the most generous rider I ever met. If it works out that it's best that he does all the hard work, then without the slightest complaint he just goes to the front and pounds out the watts. And further to that, he never, ever reminds people later that he did all the work.

At Bolsena we had to get more water. We pulled into a bar at the base of the climb. I pulled out some money to buy some bottled water. Italians always insist upon putting bottled water in our water bottles, horrified that we would consider drinking tap water. The tap water in Italy is perfectly fine but it doesn't taste as good as the good bottled stuff. But this barista (perhaps for the first time in all my visits to Italy) motioned to put Ted's bottle under the faucet. Ted said of course that was fine. I told the barista that it was "perfetto per il cane" (perfect for the dog), pointing to Ted. The barman wasn't exactly sure what I meant, but gave him enough water to see us back to Orvieto.

Italians, unlike Americans, by the way, never walk with bottles of water in hand. Italians generally don't eat or drink when on the move. That would violate Italian Law Number One: One must always look good.

The climb from Bolsena up to Biagio at the top of the mountain is a nice, 39-21 climb that can be spun, with an occasional drop to the 23. Across the top of the mountain Ted just pounded away into the wind at about 20 miles an hour. He must have smelled the spaghetti cooking.

We ended up in Orvieto with 60 miles done in four and a half hours. No land speed records, but was a tough ride that has to be classed as one of the best I can remember.

This is my second visit to Orvieto. In 1999 Carol and I explored every nook and cranny of this tiny, remakable town. When I visit a town that is new to me I feel compelled to learn and study and visit every significant monument, building and work of art. I feel that I have to work at my vacation. The beauty of a second visit to town like Orvieto, a place for which I have a powerful affection, is that this strong compulsion has been satisfied. Now I can stroll and enjoy the town for its ambience and spirit. I can revisit those places I particularly remember with fondness.

|

||

|

As you can see from this picture, Orvieto has a fairy-tale feel. And there's my own Princess, Carol. |

||

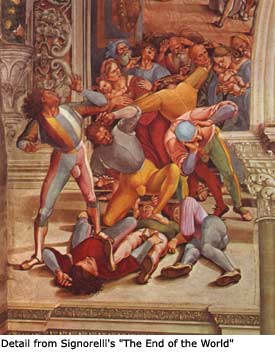

The first place we went to was the Cathedral, or Duomo in Italian. Inside the Orvieto Cathedral are the Luca Signorelli paintings of the Apocalypse. In the mid 1400's, Fra Angelico started the project. But fifty years later the good people of Orvieto had yet to have their painting finished. They called in Signorelli who proceeded over a six-year period to execute the masterpiece of his career. This painting is in spirit much like Michaelangelo's Last Judgement. The painting seems to be mostly an excuse to explore and depict the human body. Signorelli has been accused by people with more knowledge about these things than I to have a superficiality about his work. He has been accused of lacking depth. This is cant. The paintings are powerful and intentionally disturbing. His own self-portrait in one corner, standing next to Fra Angelico, is a masterpiece in itself.

|

||

Now this may be Signorelli's Last Judgement. But here is how Puck Magazine showed what it will all come to for us cyclists.

|

||

There was one unvisited site left in Orvieto. What was for me an uncharacteristic lack of curiosity kept me from visiting St. Patrick's Well during my first visit. In the early 1500's, since the Popes were using Orvieto as a refuge, it was thought that a well should be sunk to ensure a water supply in case of a siege. The engineers had to go down 200 feet to find water. The engineers then decided to do an audacious thing. In this deep well they built a double helix. There are two stairways so that donkeys can descend, pick up water and then ascend without meeting a donkey coming the other way. This double-stairway required the builders to make the well quite big. I think it is 15 meters (47+ feet) in diameter

Saturday, April 2: Another cool, perfect day in Umbria. The lady who had been unhappy with our eating so early the day before now started feeding us herself just a few minutes after seven. That's the hospitality I'm used to from this hotel. We stuffed ourselves to the threshold of pain and set off in a northeast direction. Our plan was to ride for a while along the valley floor to give our legs a chance to spin and warm up for a bit before the climbing began. I showed the map to the hotel owner and pointed out the road I wanted to take. I told him I wanted to go to Peglia.

"Oh, Monte Peglia. Molto Bello."

"Monte", I asked?

"Si, Monte Peglia," He answered.

I looked at the map again. There was an "M." for "Monte" hiding on the other side of the road on the map. I didn't look closely again to see the elevation of nearly 3,000 feet. I thought this would make for a jolly first hour or so. It would let me recover from yesterday.

The road we wanted to take was a tiny one, obviously little traveled. We headed north on route 77. I was quite nervous because if we missed the road we would be headed to Arezzo, 120 kilometers up the road.

There it was, the sign for Morreno. What luck! We turned right and started to go up immediately. Into the little ring, back up to the 21. This wasn't a tough climb, but it wasn't the easy start that I had in mind. Now I looked at the map and figured out that we had a couple of ours of climbing ahead of us. There was no traffic. We passed farm after farm with olive trees and vineyards. There were fields that had been prepared for row crops but it appeared than none had been planted yet. The grapevines had just begun to bud.

Finally we could see a small forest of communications towers off (and up!) in the distance. That was obviously Monte Peglia. After two hours, we had covered the magnificent distance of twenty miles. The view was amazing. I had ridden this road six years before but I couldn't remember it. We traveled along the ridge line of the mountain for some distance before doing a long, steady descent into our first large city, Marsciano. Our plan was to continue east from there and circle around south to the ancient city of Todi. I asked directions for the next city we wanted, Collepepe. I clearly misunderstood what I was supposed to do. We end up riding due south to Todi. Ted, not wanting to miss a millimeter of riding, wanted to go back. I looked at the watch and looked again at the road between Todi and Orvieto and suggested that we had enough road to chew on for one day.

There are two roads from Todi to Orvieto. One is a nice, wide, flat affair that if one were in a hurry, one would take. The other, Route 79bis, looks like intestines on the map. We took the slower, picturesque road. With the right turn onto the road we had to get out of the saddle to keep the bikes going. For the next fifteen kilometers we just worked our 39 tooth rings in the 21 and the 23. By now we had almost four hours on the bikes and I was getting tired. Not in trouble tired, but tired enough that the snap had gone from my legs. The wind that we had been fighting earlier was gone. We were on a road with no cars and not even a hint of a breeze. At Le Caselle we were at about 2,000 feet. We rode along the ridge of the mountain before doing a long descent. Oh, that felt good.

|

|||

|

Chairman Bill enjoying a spectacular day in Umbria |

|||

Then, back up the hill. We were out of water, out of food, out of legs and out of butt. We were shot and the road signs argued with each other as to how far we had to go. One sign would have it at 20 kilometers. Another at 15 then one at 21.

At last we made the final crest and could see Orvieto off in a short distance. We rocketed down the hill and then climbed slowly up to Orvieto. 79 miles of almost pure mountain work that took five hours. We were sore, tired, hungry, and thirsty and utterly satisfied with the best ride of the trip.

Sunday, April 3. Transfer day. Pope John Paul had passed away the evening before. The only sign of his passing in this cathedral town was the tolling of the bells a little after eleven at night. The next day, as we loaded the van with our bikes and luggage, lots of people were headed for church for the Sunday sevice.

We drove to Arezzo up in Northeastern Tuscany. The hotel we chose, the Continental, has my gold-star approval of a place for cyclists to stay. They have a good place to keep the bikes in the hotel. No hiking to a garage or any of that nonsense. They are used to catering to cyclists, so there is a kindness and simpatico for our problems and idiosyncrasies.

That evening, our good friends, the Paoletti sisters, arrived. Valeria now does a lot of the oral history interviews for Torelli and Road magazine. Francesca is a gifted cartoonist, as anyone who has checked out the "Torelli Comix" on our web site knows.

Monday, April 4: "Bill, if you are planning to go riding with Franco Bitossi, I must warn you. It will go very, very bad for you. He will break your legs."

"But Paolo, he is sixty years old," I protested.

"Ah, but Bill, he is Franco Bitossi, " was the reply, knowing that this was sufficient explanation.

This was the caution that Paolo Guerciotti, the famous racer and bicycle maker, had given me when I first tried to go riding with the great Franco Bitossi about five years ago. It wasn't until today that Bitossi and I were able get our schedules to agree.

Early this morning Franco Bitossi was going to come from Empoli, an hour's drive away, to spend the day with us.

For those of you who are reading this and to whom the name Bitossi means nothing, a little review might be in order. Bitossi has 147 official professional victories to his name. Among some of the more important wins is the Points Jersey for the 1968 Tour de France (it was orange, not green in those days). He has worn the Maglia Rosa, the Giro d'Italia's equivalent of the Tour de France Yellow Jersey. He was such a complete rider that he has won both the sprinter's and the climber's jerseys in the Giro. Thrice he was the Giro's King of the Mountains. He won 21 Giro stages, just behind Fausto Coppi's 22. Classic victories are his as well, including two Tours of Lombardy.

Bitossi was my favorite rider of the 1970's (he retired in 1978) because he was a very cerebral racer. He possessed every physical gift a rider could want including the stunning ability to unleash a magnificent searing attack in the final kilometers of a race. These attacks usually left the other racers demoralized and unable to respond. As he would fly down the road they could only work to limit their loses. Bitossi followed the mantra of Tour de France founder Henri Desgrange. He used his "Head and Legs". Look at almost any picture of the final kilometers of any important race that Bitossi was in. You'll almost always see Bitossi in that final front group racing for the finish line. When Bitossi talks about his regrets in races, they are few. They always seem to be about making some small tactical error that he feels he should not have made. To me, Franco Bitossi is the thinking man's racer. And, in this day of disillusionment with dope-taking athletes, Bitossi was clean. He had to be. His unpredictable tachycardia attacks made amphetamines, the drugs of choice in his time, an option that would simply kill him.

|

||||

|

Franco Bitossi on his way to a solo victory in the 1967 Tour of Lombardy |

||||

A few minutes before eight in the morning I came down to our hotel lobby to be told that Signor Bitossi had already stopped in. He was parking his car and would be riding his bike back to our hotel in a few minutes. Decades of celebrity and hero worship have not changed the man. At no small trouble and effort he was willing to come visit us, not the other way around. It's hard to explain to Americans how much the Italian people love this man.

When he arrived I showed him our rider maps and asked him where he wanted to go. He, being an Italian gentleman, deferred to us. We told him that since he was the local and had ridden every road in the area many times, he should pick the route. He said that this was his first ride of the new season and that he wanted to ride for just a couple of hours. Fine, I said. Two hours it was.

He was uncomfortable with the idea that we were shortening our ride to be with him. Compare this kind, humble attitude to that of one American pro who, when he disagreed with a race official's decision, screamed, "Do you know who I am?"

I told Signor Bitossi, "sono il suo gregario": I am your domestique.

Resigned to having his American fan club stick to him like glue we headed off into the hills of Tuscany. Since he spoke no English, he had no choice but to converse with me in Italian. Given my rude grasp of the language of Dante and Petrach, this was a rough fate for such a nice man.

Bitossi took the point and easily led us through the complex streets of Arezzo and out into the open country. I was right. He had ridden these roads many times over the last five decades. He mentioned that now he had to some degree let his interest in cycling be eclipsed by other passions, primarily the cultivation of olive trees.

Yet, as we rode he pointed out anything along the way that might have something to do with cycling. It was clear that almost thirty years after retiring from racing, the bicycle was always on his mind. As we were cruising along one slightly twisty, undulating bit of road, he couldn't help remarking, "This is a perfect road to make a breakaway ("fuga", or flight, in Italian). You can escape and be out of sight immediately." Always thinking, always thinking.

|

||

|

Kyle and Chairman Bill with the great Franco Bitossi |

||

"Here is the factory that sponsored the old Famcucine pro team. It is out of business now," he said as we passed an old dilapidated building with faded and peeling paint. The glamorous days of sponsoring racing heroes who were lionized by millions of fans were gone for this once famous company. The weathered walls reminded us of the fragility of glory and success.

We passed a cemetery. We followed Franco in so that he could pay his respects to a friend and fellow racer who had died as a young man.

Constantly he spoke of what is now his first love, olive trees. All along the road, the hills were covered with carefully tended olive groves.

"Smell that? That odor is the olive blossoms perfuming the air. This is the perfect place for olives, a little bit above sea level. You cannot grow good olives near the sea. I used to have lots of olive trees, but the work is too hard for me now. I have sold off all of my olive groves except for four trees." He now cares for the trees of other growers.

We stopped at one olive orchard and walked up a steep driveway to the owner's house. Franco wanted to have a short visit with a friend. No one answered the door. He called out to the field hands and they said his friend was in a far orchard. Bitossi never missed a single opportunity to pay his respects to a friend or give even a stranger a boisterous and cheerful greeting.

As we rode, I could only wonder at the legs churning the cranks on the bike in front of me. These were the legs that had challenged and regularly beaten Merckx, De Vlaeminck, Gimondi, Zilioli, Motta, Poulidor and the other great men of cycling's golden age. To win a race in the late 1960's and early 1970's you had to beat immortals. In other words, to win, you had to be one yourself. As we descended one curvy, challenging piece of road, Bitossi effortlessly carved a perfect line. At sixty-five, the man was still an artist on the bike.

I got behind him and playfully gave him a push up a hill. That brought back memories. "During my first year as a pro that is what I had to do. I had to push my captain, Gaston Nencini [1960 Tour de France winner], up the hills. It was terrible, hard, brutal work."

"Nencini? I have read that he was unbelievable on the descents."

"Yes, he was incredible, as were Francesco Moser, Italo Zilioli, Rini Wagtmans and Lucien Aimar [Tour winner 1966]. You had to be careful riding with these men because they were so good at descending. Merckx was almost as good, but because of his responsibilities and position, he didn't usually descend like the others."

"We should stop here and turn around." We had been out for over an hour and a half. He was clearly feeling better than he thought he would on the year's first ride. He wanted to send us out into the mountains to spend a day riding. Ted decided to do just that. Franco showed him a good route that would be really challenging. Kyle and I were enjoying his company too much to be anything more than limpets.

As we rolled along it seemed that everyone knew and liked Franco Bitossi. He really owns this part of Tuscany. People waved to him and he called out to almost everyone we passed. We stopped at a little outdoor market in Loro so that Franco could talk to a man he knew who was selling cheese. The cheese seller sliced off several generous pieces of his hard pecorino (sheep's milk cheese) for us to eat. This was good eating!

We were standing just outside a Bar. "Caffe?" Bitossi asked.

"Si. Vorrei un cappucino," I answered.

"No cappuccino! Caffe per te!".

"Preferisco cappuccino."

Bitossi was firm. I was not to have a cappuccino (espresso with hot frothy milk) this late in the morning on a ride. I was to have a straight espresso coffee. The milk, he said, might react in my stomach during the ride. He was Franco Bitossi so an espresso it was along with a delicious piece of lemon pie.

He told us about the 1964 Giro. "On the first stage I had a tachycardia attack [he was plagued with heart problems most of his career] and had to wait for it to pass. I lost eleven minutes that day. Jacques Anquetil won the Giro that year, but I finished nine and a half minutes behind him."

"That means you rode the rest of the Giro faster than the winner," I replied. "Barring that heart attack you surely would have won the Giro that year."

"Bo?" [Who knows]. He shrugged his shoulders. He had long ago learned to accept the irreversible judgments of fate without bitterness or regrets. I must try to be more like him.

With about 20 kilometers to go we settled down to the work of getting into town without more delay. As I took my turns pulling I was deeply aware that the man on my wheel was one of the greatest cyclists of all time. I wanted to make each pedal stroke as smooth and perfect as possible. I was with the master and felt very self-conscious. While I couldn't help but worry, Bitossi himself is about the most easy-going, amiable, friendly fellow on Planet Earth with nothing but good, kind words for everyone.

Being with Franco Bitossi in Italy changes things. After a quick shower we met our good buddy Valeria Paoletti and her sister Francesca. Valeria had brought that most special of Italian Ambrosias, Buffala Mozzarella cheese. Americans do not know what Mozzarella cheese should taste like. In Italy it is made from buffalo milk and has a sharp, pungent taste. It has to be eaten within twenty-four hours of its being made. Valeria had picked the cheese up from the cheese maker in the morning before driving up to Arezzo to meet us.

But, I digress. Bitossi had a friend with a restaurant in Arezzo. As we entered, Bitossi received a respectful greeting from the owner. I missed some of what was said, but when the nature of the precious cargo Valeria was carrying was made known to the owner, he was very happy to serve it to us in a way that would do it justice. He then told us that he would prepare a meal of good things and it was left at that.

The waiter brought a plate of fresh tomatoes, prosciutto, olive oil and oregano to go with the cheese. What way to start a meal. Then the little plates of delicious foods started coming. Bread soup, pasta ribbons with hare and pork meat, I can't remember it all. It was a meal fit for the King of Two Wheels and his court.

The entire time we ate Bitossi entertained us with stories about his career. I asked him about the Tour of Flanders, thinking that the many short, very hard climbs were well suited to his ability to put out sharp, hard bursts of power. "You are correct," he said.

He explained that one time he was away with Merckx and dropped him on the Mur de Grammont (the club of men who can say that is exclusive, indeed). Merckx then clawed his way back to Bitossi and then refused to work with him because three of Merckx's teammates were chasing. Bitossi sat up as well and Merckx' men caught them. They started attacking Bitossi, one after another. And on one fateful corner Merckx and a couple of his teammates got a small gap. Bitossi had a rare moment of tactical failure and didn't immediately close up to them. Merckx took off and Bitossi chased for all he was worth, but the mighty Belgian was gone.

While he liked Flanders, he had nothing but bad luck at Paris-Roubaix. One time, after getting caught behind a crash, his shoe was sucked off his foot in the mud. There was no way to get through the fallen riders and mess of cars to catch leaders after that.

"Giro de Lombardia? You won it a couple of times didn't you?"

"Yes. One time [Felice] Gimondi was away. Merckx was chasing him and [Gianni] Motta sat on Merckx's wheel. Motta was Gimondi's teammate so he was doing what he could to slow Merckx. Merckx would attack and try to catch Gimondi but he always had Motta with him. I just sat behind them as they exhausted themselves attacking and chasing. Finally I could see that Merckx had done what he could and that both he and Motta were no longer threats and that Gimondi had been out in the wind for a long time. Boom, I took off and flew away from them and came in alone to win the race."

|

|||

|

The king and his Court. From left: Carol, Bill, Valeria, Bitossi, Francesca and Kyle. |

|||

That was classic Bitossi. Let the other guys fight between themselves and lever him into a good position and then put the hammer down. Bitossi said that he preferred to go with about a kilometer to go. At that point, when he unleashed one of these devastating escapes with massive reserves of power still untapped, he could cross the line without having to worry about sprinting.

After lunch we went up to our hotel room. Franco had brought his entire collection of photographs. His career was in one shopping bag. Because Bitossi had other commitments that day we had a little over an hour. We picked the most interesting of them and scanned them into Valeria's laptop. One picture was particularly interesting. He and Roger de Vlaeminck are sprinting for the line. There is a crash behind them. De Vlaeminck has already started to throw his bike across the line while Bitossi looks like is still turning the pedals.

"Who won this race?"

"This was the Trofeo Langueglia. De Vlaeminck crossed the line first, but he had pushed me. De Vlaeminck was relegated and I won the race."

That was it. Franco had to go. We went downstairs to wait for him return with his car. Just before he took off he gave Valeria the phone numbers of Vittorio Adorni, Italo Zilioli and Gianni Motta. Neat Rolodex.

I just remembered my last question. "May I import your olive oil for your American tifosi?"

"This sounds interesting."

"We'll talk about this later," I replied.

Zoom, he was off. What was it Dorothy Parker wanted on her tombstone? "Pardon my dust." That should be Franco's motto

The day was still young. We had tickets to see the Piero della Francesca fresco cycle in the San Francesco church. We had tried to see the frescos a couple of years ago but couldn't because reservations are required. Only 25 people at a time are allowed into the side chapel with the paintings. With the Paoletti girls with us we had an admirable guide. Francesca has studied and continues to study fine art and art history. She is profoundly knowledgeable about almost anything that involves a paintbrush or pencil. I need all the help I can get.

While it is generally acknowledged that the paintings, depicting the story of the true cross from its beginning as a tree planted by Adam's sons is a landmark work by a Renaissance master, I found it to be a bit spotty. Some writers say the perspective was done to perfection. That is clearly not true. Some bodies Piero painted are real works of art. Others are clumsily portrayed in poor and unrealistic poses. I don't know if this were because Piero employed helpers as was the case of almost all master artists of the era or if there were moments of haste mixed with times of deep inspiration. In any case, for me the effect was spoiled in places by what is normally the strong point of Tuscan art, the initial layout and drawing.

Tuesday, April 5: Since we were checking out Wednesday, this was going to be our last real ride. We wanted it to be a good one. We decided to head into the Alpe de Catenaia, the mountains north-northeast of Arezzo.

Again, as we have been this all this trip, we were lucky (OK, paranoid and checking at almost every intersection) to find the little road off the main highway that would take us to our first checkpoint, Anghiari.

There was almost no traffic and the sun was warming the air. Almost immediately we started to climb. At first it was in the six percent range, which we were able to spin up with our 19s and 21s. After about ten kilometers the hill started to bite. As a prelude to the day's real riding there was a sign warned us that we were about to climb the Passo Scheggia. I didn't bring my inclinometer, but the map says that we were climbing a road that was in the seven to twelve percent range. It felt and looked like nine to ten with a couple of tough spots that were clearly at least twelve percent. Now were were in the 23s and needing them. Because I was so tired from the week's riding I was having trouble working hard enough to get my heart rate up into the 150s. Slowly my legs started to respond as we pushed our way up the mountain.

Cresting the summit we had a gentle descent into Anghiari. Anghiari was the scene of a Florentine victory over Milan. This battle was the subject of Da Vinci's painting in a great face-off in 1503 between Michelangelo and Da Vinci. Both had been contracted by Florence to paint scenes in the city hall of Florentine victories. Both worked with intensity, preparing the preliminary drawings, knowing that the most fanatical of art critics in the world, the people of Florence, were watching them intently. Neither finished his job. Leonardo botched the application of the paint and Michelangelo was called away by Pope Julius the Second to other projects.

At Anghiari we turned almost due north. Our goal was Chiusi della Verna, the north apex of our planned ride. Here and there we were able to put our bikes in the big ring, but that was the exception, not the rule. This is a grunt road that shows no mercy. We crossed two passes whose names are not on the map.

But, in return for the brutal, tough climbing we were rewarded with a road that for all intents and purposes, had no cars. As we climbed ever higher like Shelly's Skylark (and we were indeed, blithe spirits), the valleys below and the mountains ahead were revealed to us. We felt like explorers, seeing this wonderful landscape for the first time.

Let me write this. If the reader gets to Italy and has a chance to ride from Chiassa, a little town just north of Arezzo, up to Chiusi della Verna, I promise that he will spend several of the best hours of his life enjoying one of the most beautiful roads that one could ever imagine riding.

At Chiusi, we had managed to ride only 30 miles, but it was almost all done at under ten miles an hour. After three hours of tough, hard riding we had only come this short distance. But oh, what a fine distance it was.

We turned south-west and luckily, mostly followed the ridge line and didn't have to give up all of our altitude yet. Chiusi was at 960 meters. The towering mountain behind Chiusi, Monte Penna continues on up to about 1300 meters.

We passed through Fontanelle whose famous spring water is bottled and shipped all over Italy. At the next city, Chitignano, we had to stop and get more water. Now, we had a decision to make. Did we want to get on the road straight back into Arezzo, following the Arno along Route 71 almost due south or did we want to head back into the mountains and circle and loop a bit back. Not expecting the road we had ridden to be a tough as it was, I had just eaten the last of my food and my legs were rapidly losing what little strength they had. It was eleven thirty in the morning and at our luckiest, we had at least an hour to go. I decided to join the trucks and take the shortest way back. Ted, hearing me talk about lunch, was seduced into heading back with me and getting a plate of hot spaghetti into him as fast as possible.

From Chitignano, we had a long, very fast descent over a beautiful road that had been newly resurfaced.

That and any other luxury ended when we hit the busy highway. For about 18 kilometers (12 miles) we steamed along at about 20 miles an hour until we could turn off and ride a parallel road into town. Four and a half hours totaling 63 miles (100 kilometers) and we were cooked. Thrashed. Finished. Fried. Done.

Wednesday, April 6. Our last real day in Italy. We had time for a short ride. We retraced our Bitossi/Monday ride. All the other possible routes needed some real time to get out into the hills, time we didn't have. We did our ride feeling a touch melancholy. The party was about over. We packed up the van and headed back to Milan.

On the road back to Milan I asked Carol, "What do you think of going back to Ronta as a first city next year?"

She didn't roll her eyes. Honest.