Cycling’s Twenty-One Greatest Climbers

BikeRaceInfo's Best Climbers: Riders 10–6

Les Woodland's book Tour de France: The Inside Story - Making the World's Greatest Bicycle Race is available as an audiobook here. For the print and kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Riders are listed in reverse order. Rider number one will be the rider in our judgement to be cycling's greatest ever climber.

Note: I put this list together in the early 2000's. Since then, a very kind reader noted that one rider is missing (I didn't include active riders), Alberto Contador, who won seven Grand Tours and was a superb climber. I would rank him about seventh, along with Luis Ocaña.

Cycling's Greatest Climbers intro | Climbers 17–21 | Climbers 16–11 | Climbers 5–1

10. René Vietto (1914–1988)

René Vietto in the 1934 Tour de France

Cycle historian Les Woodland called René Vietto one of the greatest riders to have never won the Tour de France. Riding to work at hotels in Cannes, Vietto became fit and started entering and winning races. His startling abilities as a climber were soon very apparent. In 1932 he went for a training ride with a famous guest, Alfredo Binda, who gave him training and racing advice.

In 1934 Vietto was selected to be a member of the French National Team in the Tour de France to ride in support of 1931 Tour winner Antonin Magne. Back then the teams were organized on national rather than trade team lines. It was in stage fifteen that Vietto won everlasting fame.

From The Story of the Tour de France: “The next stage, number fifteen from Perpignan to Ax-les-thermes, is the real beginning of the story of Vietto's sacrifice and his rise to immortality. On one of the earlier climbs of the day Magne tried to test Martano with an attack, but Martano was not to be dropped. The big climb of the day was the 25-kilometer long road up the Puymorens. René Vietto led Magne and Martano over the top. On the descent Magne crashed and broke the wooden rim of his front wheel. Seeing the Yellow Jersey's misfortune, Martano jumped away in an effort to put distance between himself and Magne.

"'René, give me your bike,' Magne demanded of Vietto

"'No, but take my front wheel.'

“Vietto dutifully gave his team leader the front wheel of his bike. Unfortunately, Magne's frame was bent in the crash. When Georges Speicher—who had been behind on the climb—showed up, Magne took Speicher's bike. Magne was able to hook up with Lapébie and chase down Martano and the rest of the leaders. Magne limited his time loss that day to a mere 45 seconds and kept his Yellow Jersey. Vietto had to wait several minutes for the support car to bring him a replacement. He and Speicher finished together, 4½ minutes behind the stage winner Lapébie.

“There is a picture of Vietto, weeping by the side of a mountain road, the front wheel of his bike missing. He knows that the Tour is going down the road without him. In some pictures of the scene a man in street clothes holds a smashed wheel in his hands. Vietto's anguish, 70 years later, still moves me when I see this picture. I wasn't the only one affected by the scene. The entire cycling world was touched by the scene of a man who made a huge sacrifice and was abject in the realization of the cost of that gift. The next day the newspapers proclaimed him Le Roi René (King René).

Vietto by the side of the road

“Things did not get better for the brilliant young climber. The next day, the stage from Ax-les-Thermes to Luchon was another big day of climbing with the Port, Portet d'Aspet and the Ares passes to overcome. Vietto was first over the Port and rode ahead of his team leader Magne who was keeping an eye on second place Giuseppe Martano. Over the next mountain, the Portet d'Aspet, Vietto was slightly ahead of Magne. He eased a bit so that he could be with Magne on the descent. Magne was still following Martano when he hit a rock and crashed. This time Magne wrecked his rear wheel. Vietto, thinking that Magne would be joining him shortly, continued. This was over a half-century before earphones. Often, in the "fog of war", riders are confused about what is actually going on in a race. A Tour course marshal on a motorcycle zoomed up ahead and told Vietto that his team leader had crashed and was stranded without any teammates. Lapébie was off the front and the rest of the team was well behind.

“Hearing the news, Vietto turned around and rode back up the mountain against the tide of descending riders in order to reach his leader. Magne couldn't believe his good fortune. He grabbed Vietto's bike and took off after Lapébie who was now waiting for him and could help him regain the leaders. Adriano Vignoli, the stage winner, was long gone, but Magne and Lapébie did catch Martano and the rest of the riders who were up the road. Again Vietto had to wait for the service car to give him a new bike. He came in over eight minutes after Vignoli, but only about four minutes after Magne, Lapébie and Martano. Vietto’s selfless move preserved Magne’s lead of 2 minutes, 57 seconds over Martano.

“But, was everybody happy? Not Vietto, who had a sharp tongue. He complained that Magne didn't really know how to ride a bike and that Lapébie had taken off looking for a stage win instead of sticking with Magne. Magne, on the other hand, was profoundly grateful to both Vietto and Lapébie for saving his race.”

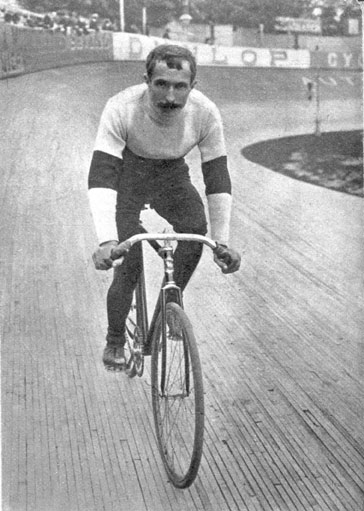

René Vietto arrives at the Buffalo velodrome in Paris at the end of the 1934 GP Wolber.

Vietto suffered knee problems form the mid-1930s on, and by the 1947 Tour de France he had endured three knee operations. He led the 1947 Tour for fifteen stages, but his weakness was time trialing (which is why he never would have won the mid-1930s Tours, despite sentiment to the contrary) and Vietto finished fifth, more than fifteen minutes behind winner Jean Robic.

Vietto rode professionally from 1932 to 1953.

Vietto’s major accomplishments:

- 1934: Tour de France King of the Mountains, fifth place General Classification with four stage wins

Climbing: Vietto won the Tour’s ninth stage alone after being first over the Vars and Allos. He didn’t win stage eleven solo, but he was again first over the day’s major ascents and with Giuseppe Martano, finished more than three minutes ahead of his nearest chasers. Stage eighteen was another Vietto triumph. He was first over the Tourmalet and Aubisque and finished in Pau almost three minutes ahead of his pursuers.

- 1935: Paris-Nice; eighth place Tour de France General Classification with two stage wins

Climbing: Vietto arrived almost four minutes ahead of the field and leading over the Aravis and Tamié in the Tours stage six.

- 1938: Polymultipliée

- 1939: Tour de France second place General Classification, wore Yellow for eleven days.

- 1941: French Championships (Vichy Zone); GP de Frejus

- 1943: Circuit du Midi

- 1947: Tour de France fifth place General Classification, winning two stages and wearing Yellow for fifteen days.

Climbing: Eventual overall winner of the 1947 Tour. Jean Robic was the best climber, but Vietto showed he still had some stuff left when he led over stage nine’s final ascent, the Allos and finished with Apo Lazaridès more than four minutes ahead of hard-chasing Pierre Brambilla.

9. René Pottier (1879–1907)

René Pottier is probably cycling’s first great climber. His career was so short, his inclusion in this list is almost solely because of his spectacular climbing in the 1906 Tour de France.

René Pottier is probably cycling’s first great climber. His career was so short, his inclusion in this list is almost solely because of his spectacular climbing in the 1906 Tour de France.

After winning the 1903 amateur Bordeaux-Paris, Pottier turned professional, riding for Peugeot. By 1905 his was a top pro, coming in second in that year’s Paris-Roubaix and Bordeaux-Paris.

The early Tours de France didn’t go into the high mountains, but there were climbs, nonetheless. The 1905 Tour’s first real ascent came in stage two (of eleven), the Ballon d’Alsace. Pottier was first to the summit, but suffered a several punctures that prevented his winning the stage. A fall in the first stage caused a tendon injury that forced his abandonment in the third.

In the 1906 Tour Pottier was in a class by himself. After Emile Georget won the first stage, Pottier won the next four stages, largely ridden through the Vosges and Alps. And again, he was first over the Ballon d’Alsace. On the Ballon d’Alsace he even left behind the car of Tour boss Henri Desgrange. Stage five had the Laffrey and Bayard. Pottier was first over both and finished in nice 26 minutes ahead of Georges Passerieu and Eugène Christophe. But his dominance in the stage was greater than the numbers show. At one point in the stage he had an hour’s lead. He stopped in a bar to have some wine and let some of the others catch him. He then went on to drop everyone else again. Pottier also won the final stage into Paris.

In January of 1907 Pottier committed suicide, hanging himself in the Peugeot team’s clubhouse. He left no note, but turned out his wife had an affair while he was racing the Tour.

8. Lucien Buysse (1892–1980)

Lucien Buysse in the 1926 Tour de France

Like René Pottier, I put Lucien Buysse in the top ten climbers largely because of his dominating performance in one Tour de France, in Buysse’s case the 1926 edition. In fact, it was one incredible mountain stage in that Tour that is at the heart of his fame.

Lucien was one of the three talented Buysse brothers. Oldest brother Marcel finished fourth in the 1912 Tour de France. He was leading the 1913 Tour when his handlebars broke (they may have been sabotaged). Despite winning six stages, he could only finish third.

Brother Jules, the youngest, won the first stage of the 1926 Tour by more than fifteen minutes, giving him the lead for two days.

Lucien took a while to mature. He turned pro in 1914 and rode the Tour, but was unable to finish. After the war he abandoned the 1919 Tour. He finished the 1923 edition, coming in eighth. In 1924, riding with Ottavio Bottecchia’s Automoto team he was third and in 1925, also riding for Automoto, he came in second.

But it was in that 1926 Tour that he became one cycling’s immortals. Buysse, who spoke no French, lost a daughter two weeks before the Tour's start (some historians say the daughter died during the Tour), but his family urged him to ride the Tour nonetheless.

Riders cross a bridge in stage nine.

By the end of stage nine, the GC stood thus:

- Gustaaf Van Slembrouck: 126hr 28min 0sec

- Albert De Jonghe @ 1min 9sec

- Jules Buysse @ 6min 17sec

From The Story of the Tour de France:

"Everything changed with stage ten. This was the first of the two days in the Pyrenees. The riders were to climb the usual passes: the Aubisque, the Tourmalet, the Aspin and the Peyresourde. This Tuesday, June 30, with 326 kilometers from Bayonne to Luchon is one of the great, memorable days in Tour history.

"Lucien Buysse, who had been a selfless domestique to Bottecchia, especially in the 1925 Tour, set out to win the Tour this day. The Buysse brothers were still burning from what they thought was an unjust misfortune when their older brother Marcel, in Yellow, broke his handlebars on stage eight of the 1913 Tour. That mishap cost him the lead. Marcel Buysse was able to finish third in the General Classification, but the Buysses considered all of this unfinished business that required rectification.

"Although he was 22 minutes behind Van Slembrouck in the General Classification, Lucien Buysse was undeterred. He had predicted in Dunkirk (stage five) that this stage would be the one where he would take the lead.

"The weather conditions of the day have been described as apocalyptic, hellish and dantesque. It was certainly the worst in Tour history to that time. There was both torrential rain and nearly freezing fog. To make it worse, please remember that the passes in those days were not paved. In the rain the riders crossed the great mountains on roads of mud! These were indeed iron men on wooden rims.

The stage was so long the riders set off at 2:00 AM. There was a cold rain falling. The riders knew that worse awaited them at the tops of some of the highest mountains in Europe.

"Buysse signaled his intention by attacking on the Aubisque, the first climb. Van Slembrouck, a bigger man, was immediately shelled. Three men went clear, Buysse, Albert Dejonghe and Omer Huyse. Bottecchia could not stay with them. Desgrange's pick for the Tour, Benoit, quit the race. At the tops of the mountains freezing sleet lashed the riders. At times the sticky mud forced the riders to dismount and walk their bikes.

"On the Tourmalet, three riders made contact with the now lead duo (Huyse was dropped): Odile Tailleau, Léon Devos and Bartolomeo Aimo. Buysse was finally able to leave everyone and crest the Aspin and the Peyresourde first. He came into Luchon at 5:12 PM, almost 26 minutes ahead of Aimo and almost 30 minutes ahead of Devos. Van Slembrouck? He was 1 hour, 50 minutes behind, his dreams of Yellow shattered.

Buysse on the Tourmalet

"The average speed for Lucien Buysse's day in hell was 18.9 kilometers per hour. Only 54 riders finished that day. Desgrange, recognizing the terrible circumstances of the stage, increased the cutoff time to 40% more than the winner's time. At midnight riders were still straggling into Luchon. Some sought shelter in bars. Others made it to Luchon by car. Rescue parties were sent out to find some of the riders who were cold, starving and shattered with exhaustion.

"Lucien Buysse never finished the Tour de France again."

The day's results:

1. Lucien Buysse: 17 hours 12 minutes 4 seconds

2. Bartolomeo Aimo @ 25 minutes 48 seconds

3. Léon Devos @ 29 minutes 49 seconds

4. Théophile Beeckman @ 40 minutes

5. Nicolas Frantz @ 42 minutes 19 seconds

The General Classification after Stage ten:

1. Lucien Buysse

2. Odile Taillieu @ 36 minutes 14 seconds

3. Albert Dejonghe @ 46 minutes 50 seconds

Buysse had turned a deficit of 22 minutes into a lead of 36 minutes. This was a masterful, historic ride.

Buysse climbing in the 11th stage

Buysse’s major accomplishments:

- 1913: Amateur Tour of Belgium

- 1919: second place Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders)

- 1921: fourth place Giro d’Italia

- 1923: eighth place Tour de France

- 1924: third place Tour de France

- 1925: second place Tour de France, winning two stages

- 1926: Tour de France, winning two stages

Climbing: The 1926 Tour’s famous tenth stage had the Aubisque, Tourmalet, Aspin and Peyresourde. Buysse was first over all but the Tourmalet and finished in Luchon more than 25 minutes ahead of second-place Bartolomeo Aymo. Buysse led over stage eleven’s last climb, the Puymorens, finishing in Perpignan more than seven minutes ahead of his closest pursuer, brother Jules.

- 1928: fourth place Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders)

Lucien Buysse at the end of the 1926 Tour de France

7. Luis Ocaña (1945–1994)

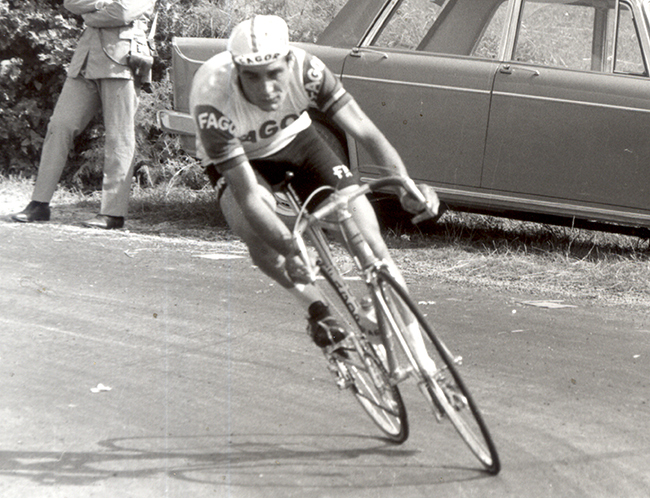

Luis Ocaña rides the 1969 GP Castrocaro Terme

Elegant, fragile, powerful, troubled Luis Ocaña was the only racer to mount a real challenge to Eddy Merckx in the Tour de France while Merckx was in his prime. But a delicate constitution caused recurring health problems that regularly forced him to abandon stage races.

Ocaña turned professional in 1968 and that same year became Spanish road champion. The next year he confirmed his talent as both a superb all-around rider (his 1971 GP des Nations win, an important individual time trial competition, showed how versatile Ocaña was) and also one who possessed special climbing talent. He was second in the 1969 Vuelta a España, winning the mountains classification and three stages. In 1970 he won the Vuelta as well as the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré.

But it was in the 1971 Tour de France that Ocaña showed how extraordinary he was. After the hilly stage ten, Joop Zoetemelk was leading with Ocaña second, just one second behind. Merckx was fourth, at one minute. A puncture followed by a delayed repair in the tenth stage was the reason for Merckx’s time deficit.

Stage eleven started at Grenoble and went over the Laffrey and Noyer before a hilltop finish at Orcières-Merlette. Ocaña took off on the Laffrey, and though Merckx gave chase, Ocaña finished almost nine minutes ahead of Merckx, putting the Spaniard in the lead.

Ocaña attacks in the Tour's eleventh stage.

Ocaña wins stage eleven alone

But the situation was going to change drastically. From The Story of the Tour de France:

"Stage fourteen, from Revel to Luchon, took in the Portet d'Aspet, the Col de Menté and the Portillon. Ocaña knew Merckx was tiring and planned to leave the Belgian and everyone else on the Portillon.

"Near the summit of the Col de Menté, a powerful, violent rainstorm with blinding hail struck. The Menté's roads turned to dangerous, potholed mud. The riders could barely see their way. Merckx, knowing that he had few peers in a descent, took off down the dangerous, partially washed out road. Ocaña and Cyril Guimard, his companions over the crest of the mountain, were able to descend with him. Presciently, Ocaña's director, Maurice de Muer warned Ocaña against descending with Merckx.

"Four kilometers down the mountain, Merckx crashed, taking Ocaña with him. Merckx fixed his chain and was back riding in a flash. Not so Ocaña. He needed a new wheel. Ocaña's team BIC service car parked to take care of him. Zoetemelk came careening down the mountain. He swerved to avoid the BIC service car and slammed into Ocaña instead. Then, Joachim Agostinho came flying down the hill and also hit Ocaña.

"Ocaña, in a coma, was taken away in an ambulance. Jose-Manuel Fuente won the stage. Merckx followed in 6½ minutes later with van Impe, Aimar, Zoetemelk and Vicente Lopez-Carril.

"Ocaña later fully recovered, but his Tour was over. Merckx was again in Yellow. In deference to the fallen Spaniard, Merckx refused to wear the Yellow Jersey until the day after."

Ocaña completely dominated the 1973 Tour, which Merckx did not ride. Second-place Bernard Thévenet finished almost sixteen minutes behind the Spaniard.

Though Ocaña went on to two fourth places and a second place in the Vuelta, he never again finished in the Tour’s top ten.

Luis Ocaña in the 1973 Tour. That should be José-Manuel Fuente on his wheel.

Ocaña retired in 1977 to care for his vineyard. He committed suicide in 1994, troubled by both failing health (he had cancer and hepatitis C) and financial problems.

Ocaña’s major accomplishments:

- 1968: Spanish Road Championships

- 1969: GP du Midi Libre; Vuelta a Rioja; Catalonian Week; Vuelta a España mountains classification; Vuelta a España second place General Classification; Mountains Classification, winning three stages

- 1970: Vuelta a España General Classification; Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

- 1971: Grand Prix des Nations; Tour of the Basque Country; Vuelta a España third place; Volta a Catalunya; two stages in the Tour de France

Climbing: stage eight of the 1971 Tour de France finished atop Puy de Dôme where Ocaña finished alone, 7 seconds ahead of Joop Zoetemelk. Ocaña led over stage ten’s last ascent, the Porte. And of course, there was the famous stage eleven with its hilltop finish where Ocaña left Merckx almost mine minutes behind.

- 1972: Spanish Road Championships; Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

- 1973: Tour de France General Classification, winning six stages; Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré; Tour of the Basque Country; Vuelta a España second place General Classification; Trophée des Grimpeurs

Climbing: Ocaña won the Tour de France’s stage seven-a alone after being the first over the Solève. Stage eight finished atop Les Orres, where Ocaña again arrived alone, a minute ahead of renowned climber José-Manuel Fuente. Ocaña led over stage thirteen’s final ascent, the Portillon, then he motored on in to Luchon, where he arrived 15 seconds ahead of his closest chaser, Joop Zoetemelk. And finally Ocaña was first to the top of Puy de Dôme at the end of stage eighteen.

- 1974: fourth place Vuelta a España

- 1975: second place Tour of Andalucia; 4th place Vuelta a España

- 1976: second place Vuelta a España

Luis Ocaña descends in the 13th stage of the 1973 Tour.

6. Eddy Merckx (1945– )

Eddy Merckx is the greatest bicycle racer ever. He entered about 1,800 professional races and won 525 of them. No one else is even close. And he won every kind of race, stage races, classics, six-day, cyclo-cross, time trials and set records that stood for years, including his incredible World Hour Record set in 1972. If Merckx had not suffered a terrible crash in a motor-paced race in the fall of 1969 that caused him trouble the rest of his career and made climbing painful, he surely would have had a higher place on this list.

Eddy Merckx is the greatest bicycle racer ever. He entered about 1,800 professional races and won 525 of them. No one else is even close. And he won every kind of race, stage races, classics, six-day, cyclo-cross, time trials and set records that stood for years, including his incredible World Hour Record set in 1972. If Merckx had not suffered a terrible crash in a motor-paced race in the fall of 1969 that caused him trouble the rest of his career and made climbing painful, he surely would have had a higher place on this list.

Merckx won five Tours de France, taking a record 24 stage wins along the way. He also won five Giri d’Italia with 24 stage wins and one Vuelta a España. Of the Classics, he won Milano-San Remo (a record seven times), Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders), Paris-Roubaix, Liège-Bastogne-Liège and the Giro di Lombardia. He was World Road Champion three times (once as an amateur, twice as a pro).

Merckx’s 1969 Tour de France, which he rode before his big crash, stands out. Stage seventeen showed what he could do in his prime.

From The Story of the Tour de France: "Stage seventeen was a 214.5-kilometer epic stage with the Peyresourde, the Aspin, the Tourmalet and the Aubisque. Over the first two mountains, Merckx was content to let Joaquin Galera be first over the top.

"On the ascent of the Tourmalet with most of the would-be contenders for company, Merckx attacked. Only his teammate and the tallest man in the pro peloton, Martin Vandenbossche, could go with him. The others could only watch.

Over the top of the Tourmalet his lead over his chasers was only a few seconds. On the descent Merckx again showed what a complete rider he was, descending far faster than his chasers. He arrived at the bottom of the Tourmalet alone and a minute ahead of the chasing group. Given the commanding lead Merckx had in the General Classification and the fact that there were still 140 kilometers and the Aubisque left in the stage, the others felt that it was unlikely that Merckx would continue to press his advantage. The initial motivation to drop (actually spank) Vandenbossche and continue alone was Merckx's resentment that Vandenbossche had accepted a contract with another team, Molteni, for the coming year. Vandenbossche was now back in that lead group of chasers, loyally working to protect Merckx.

Eddy Merckx (right) climbing in stage sixteen of the 1969 Tour.

With 105 kilometers left, Merckx took on food and continued to forge ahead. He later told L'Équipe 'I was just 'walking', and when I heard the time gap I decided I had to carry on.'

"At the top of the Aubisque, wondering if he should wait for help, he was told that he now had a lead of seven minutes. He decided to keep on with his breakaway. Merckx flew down the hill and over the rolling countryside that stood between him and the finish line.

"At the top of the Aubisque, wondering if he should wait for help, he was told that he now had a lead of seven minutes. He decided to keep on with his breakaway. Merckx flew down the hill and over the rolling countryside that stood between him and the finish line.

"He crossed that line 7 hours, 4 minutes, 28 seconds after he started. The second rider to finish was Michele Dancelli, 7 minutes, 57 seconds in arrears. Pingeon and Poulidor were right behind Dancelli. In a single day Merckx had about doubled his lead.

"Coming in at 14 minutes, 49 seconds was the major group containing Gimondi, van Impe and Agostinho. Taking into account the narrowing differences between riders' abilities that has steadily occurred over the past 100 years, Merckx's 1969 stage seventeen ride has to be one of the few Tour exploits that can be considered on par with Coppi's 1952 stage eleven victory.

"The new standings showed how Merckx had shattered his rivals:

- Eddy Merckx

- Roger Pingeon @ 16 minutes 18 seconds

- Raymond Poulidor @ 20 minutes 43 seconds

- Felice Gimondi @ 24 minutes 18 seconds

- Andres Gandarias @ 29 minutes 35 seconds

"By the end of the 1975 season, Merckx’s non-stop year-round racing (he raced six-days in the winter rather than let his body get a rest) had left him ragged at the edges. He had enjoyed years where he won 50 or more races, but he won only 15 of 111 races entered in 1976, 17 of 119 in 1977 and none of the five he rode in 1978."

Merckx raced professionally from April, 1965 to March, 1978

Merckx’s major accomplishments: Merckx’s career was so extraordinary, that except in the case of the Tour de France, I have only listed his big wins:

- 1966: Milano-San Remo

- 1967: Milano-San Remo; Gent-Wevelgem

- 1968: Tour of Sardinia, Paris-Roubaix, Giro d’Italia General, Mountains and Points Classifications; Tour of Catalonia

Climbing: In the Giro d’Italia, Merckx led over stage eight’s big climb, the Ghimbegna. In stage twelve Merckx won the hilltop finish at Tre Cime di Lavaredo

- 1969: Tour de France General, Mountains, and Points Classifications; Paris-Nice; Milano-San Remo; Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders); Liège-Bastogne-Liège; Paris-Luxembourg

Climbing: Merckx was probably at his peak in the 1969 Tour. Stage eight had at hilltop finish at Ballon d’Alsace where Merckx left his nearest chaser a minute behind. Merckx led over stage ten’s final big ascent, the Galibier. And of course, as described above, there was Merckx’s incredible stage seventeen where he was first over the Tourmalet and Aubisque and then rode into Mourenx almost eight minutes ahead of the small first chasing group

- 1970: Tour de France General, Points, Mountains, Combativity and Combine Classifications; Belgian Championships; Paris-Nice, Gent-Wevelgem; Tour of Belgium; Paris-Roubaix; Flèche Wallonne; Giro d’Italia General, Points, Mountains and Combine Classifications

Climbing: Merckx may have lost some his climbing edge after his fall, 1969 crash, but he was first over the last climb, the Porte in stage twelve of the 1970 Tour de France. Stage twelve finished atop Mont Ventoux where Merckx was first, more than a minute ahead of Martin Vandenbossche and Lucien van Impe.

- 1971: Tour de France General, Points and Combine Classifications; World Road Championships; Tour of Sardinia; Paris-Nice; Milano-San Remo; Het Volk; Tour of Belgium; Liège-Bastogne-Liège; Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré; GP du Midi Libre

- 1972: Tour de France General Points and Combine Classifications; Milano-San Remo, Liège-Bastogne-Liège; Flèche Wallonne; Giro d’Italia General and Combine Classifications; Giro di Lombardia

Climbing: Merckx dominated just one mountain stage of the 1972 Tour de France on his way to carving out a nearly eleven-minute lead over Felice Gimondi. Stage eleven’s last big climb was the Izoard, which Merckx was first to crest before rolling into Briançon 91 seconds ahead of Gimondi, van Impe, Poulidor and Cyrille Guimard.

- 1973: Trofeo Laigueglia; Tour of Sardinia; Het Volk, Gent-Wevelgem; Amstel Gold Race, Paris-Roubaix; Liège-Bastogne-Liège; Vuelta a España General, Points and Combine Classifications; Giro d’Italia General, Points and Combine Classifications; GP de Formies; Paris-Brussels

- 1974: Tour de France General and Combine Classifications; World Road Championships; Trofeo Laigueglia; Giro d’Italia General and Combine Classifications; Tour of Switzerland

- 1975: Tour of Sardinia; Milano-San Remo; Amstel Gold Race, Catalonian Week, Ronde van Vlaanderen (Tour of Flanders); Liège-Bastogne-Liège; second place Tour de France

- 1976: Milano-San Remo; Catalonian Week

Merckx in the Giro d'Italia's leader's Pink Jersey racing in the 1972 edition.

Cycling's Greatest Climbers intro | Climbers 17-21 | Climbers 16-11 | Climbers 5-1