Cycling’s Twenty-One Greatest Climbers

BikeRaceInfo Ranks Racing's Best Ascenders

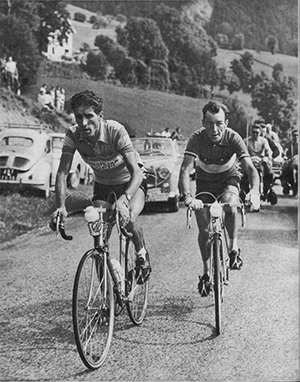

The lead group climbing in the Alps in the 1980 Tour de France Stage 17

Bill & Carol McGann's book The Story of the Tour de France, Vol 1: 1903 - 1975 is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Click on the links below to see how we ranked cycling's greatest climbers:

Climbers 5–1 | Climbers 10–6 | Climbers 16–11 | Climbers 21–17 |

Introduction:

This particular breed of bicycle racer, the climber, has long fascinated bike racing fans. These are men who have an extraordinary power-to-weight ratio that allows them to soar away from their earth-bound competitors when the road tilts upward.

The Italian word for climber is scalatore. But for that special, particularly dangerous breed of climber, the Italians have another word: scattista. That’s a climber who can explode in the mountains with a devastating acceleration, sometimes over and over again. The most famous and extraordinary of these pure climbers were Charly Gaul and Marco Pantani.

Cross-generational comparisons are treacherous. It’s impossible to know if Marco Pantani could have dropped Charly Gaul or if Gaul could have ridden away from René Pottier. Advances in bike design, training, drugs, as well as fundamental changes in the structure of racing has made each decade’s racing vastly different from the others.

Pavement is one big difference. When the Tour de France first went into the high mountains in 1910, the riders had to go over passes that were often little more than goat paths. For decades, many of the highest passes were unpaved. Most of Europe’s high passes were only paved in the last 40 years. Even the famous Gavia pass wasn’t paved until late in the twentieth century. In the early 90s only the switchback turns were paved and the straight portions were still dirt, but by 2000 the pass was entirely paved.

Racing at the twentieth century’s start, Pottier rode a fixed-gear bike, suffered through 400 kilometer stages that began before sunup, and had strychnine, camphor and wine available if he wanted to take drugs. The Tour de France’s first King of the Mountains, Vicente Trueba (our climber number 20), was first over many of the great passes riding a fixed gear.

In the 1950s Gaul could ride an efficient 10-speed bike and it is believed he took copious amounts of amphetamines. By then a Tour de France stage longer than 250 kilometers was the rare exception.

Federico Bahamontes (left) and Charly Gaul

Racing a hundred years after Pottier, Marco Pantani had a lightweight aluminum-framed bike and could call on team and mechanical support Pottier could never have even dreamed of. Modern power meters, heart-rate monitors and blood tests have transformed training from an art to a science. Pantani could get (and surely did take) drugs like EPO and human growth hormone that allowed an already talented athlete to perform at astonishing levels.

But, given these huge changes, one thing remains the same. As Les Woodland has put it, “Speeds may have been lower back then but the one thing that was constant was that it was a race and the sensation of going flat out was the same then as now. Conditions may have changed but throwing up by the roadside hasn’t.”

So how to rank the riders? I have chosen the subjective standard of the degree to which they dominated their peers in the high mountains. Some riders, like Lucien Buysse (winner of the 1926 Tour de France), could just leave their competitors behind, sometimes building incredible time gaps.

Lucien Buysse in the 1926 Tour de France.

This was going to be list of twenty riders, but I discovered I had left off an important rider and couldn’t see anyone who should be dropped, so twenty-one it is.

As the sport has advanced, we also have to keep in mind the narrowing range of performance. 1903 Tour winner Maurice Garin won by almost three hours. Cadel Evans missed winning the 2007 and 2008 Tours each by less than a minute. This is true of all sports. Ted Williams was baseball’s last .400 hitter and that was back in 1941.

With all those caveats in mind, here is BikeRaceInfo’s list of cycling’s twenty-one greatest climbers. I put them in reverse order, rider number one is cycling’s greatest ever climber.

Click on the links below to see how we ranked cycling's greatest climbers.

Climbers 5–1 | Climbers 10–6 | Climbers 16–11 | Climbers 21–17