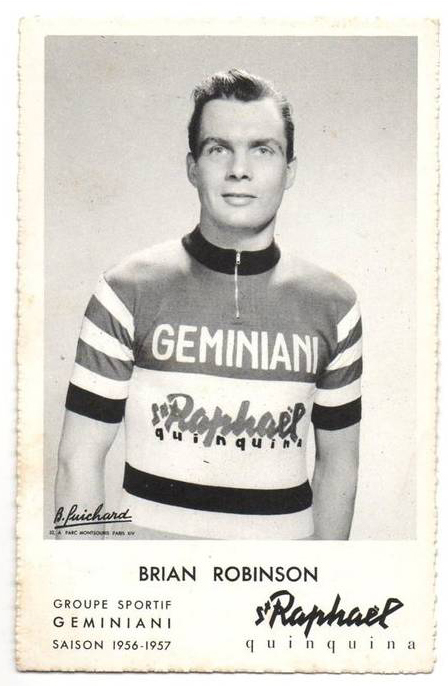

Brian Robinson:

Britain's first great cycling road professional

Les Woodland's book Tour de France: The Inside Story - Making the World's Greatest Bicycle Race is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Our story:

Before Tom Simpson, before Barry Hoban, before any of the great British cyclists of the 1960s and later, there was a determined man who made his own way in the sport. Brian Robinson was the first British rider to both win a Tour de France stage and actually finish the Tour. How he blazed a path for others to follow makes wonderful reading. Robinson was a complete rider. He could climb the high mountains with all but Gaul and Bahamontes and yet he had the sheer power to contest Milan-San Remo.

Talking to Brian is a pleasure. I wanted to do an interview that covered his entire career and he willingly submitted to about four and a half hours of telephoned questions and answers. Earlier (before August 18, 2007), I had only transcribed half of the interview. Here it is now, complete

Robinson is one of the great ones. You'll see why below.

Chairman Bill: Your racing career is fascinating, but first it would be good to delve a bit into the early 1950s British racing scene. It will allow the reader to really appreciate the magnitude of your accomplishment in becoming a good European professional. Things were very different then. Do I have this right?

Brian Robinson: Yes, that's quite true.

CB: Before the World War 2, for a number of complex reasons, massed start road racing was almost non-existent in England.

BR: That's correct, yes.

CB: And it wasn't until 1942 when a rebel cycling organization started promoting road races that British racers got a chance to do more than time trialing.

BR: That's correct.

CB: This breakaway organization, called the British League of Racing Cyclists was engaged in a poisonous civil war with the older, UCI recognized organization, called the National Cyclists' Union.

BR: Yes, that's true.

CB: I've got it right so far...?

BR: Yes, you have.

CB: This fight for supremacy continued until the UCI forced them to merge in 1958.

BR: Yes...

CB: May I add some more to this mix? Would it be correct so say the British economy was in a very bad state during the first 10 years after the war, limiting how much the British cycling industry could contribute to cycle racing?

BR: Yes, it must have had its effect. Full rationing went out, about 1954. We were restricted until then. So yes, we didn't come on stream until the late 1950s.

CB: I just want to make it clear that your circumstances were very different from those on the Continent and in the USA...

BR: Well, that's right. The people on the continent never stopped racing, really, even through the occupation. You know, in the southern half of France and in Italy they were still racing.

I had a friend who entered Europe on D-Day plus 2. He remembered that one of the cities he liberated immediately cordoned off the downtown and celebrated by holding a bike race.

So the guys must have been riding around to be able to do that, wouldn't they?

CB: You started riding early, joining your local club at 13?

BR: 14. You couldn't join a club at 13. I was riding, but not with the club.

CB: So, as a boy you were riding with older, stronger riders, getting hard as nails?

BR: Yes, that was my advantage. At least I thought it was an advantage.

CB: How and when did you start racing?

BR: I started racing in 1949, as an amateur in time trials. I was 18 then, because...well, my father didn't want me to. My brother was nearly 3 years older than me and had been racing for a couple of years. I wanted to race, but my dad said, "No, no, you're not old enough. Carry on training and at 18 you can race." That's what happened. In those days we took notice of parents.

So, I had been riding for about 5 years with older guys than myself, so I was quite fit, really.

CB: So your first racing was time trailing?

BR: Yes, it was in 1949 and we were part of the NCU [National Cyclists' Union]. We weren't in of the BLRC [British League of Racing Cyclists] at the time. The club I joined, the local club, was NCU.

CB: So all you had available when you started were time trials?

BR: Yes.

CB: So from there, I assume that at some point you were able to ride massed-start road races?

BR: Yes, in 1948 we went down to London to watch the Olympic Games. From then on the NCU, not the NCU officially, but the NCU clubs took an interest in massed-start racing. We used to have what we called "flapper" [after the name for unlicensed greyhound races] meetings, which were clandestine meetings, if you like, with little road races ‘round an airfield or something like that. Not on the road itself, in a park or on an airfield, which was private. Not on the public roads. That's sort of how it started within the NCU side of it.

CB: So you were able to segue to racing on the roads?

BR: Yes, in 1950, I think. They were using NCU officials, not with the blessing of the NCU, while running these racing around the airfields and carparks in preparation for the '52 Olympics. And that's how I came to be a road racer because I rode those events and eventually went to the Olympics in 1952.

CB: And your brother's name was Desmond?

BR: Desmond, yes. He went as well, of course.

CB: Did the long ban on road races leave British racers without the knowledge of racing tactics, feeding, coaching, physiology and equipment that the continentals had?

BR: Yes, exactly. We were, what you call riding on the britches of our backsides, if you like. We just read all we could, learned all we could from other people. There was nobody with any experience in our country.

CB: Did you have to find your own way?

BR: Well, it got worse. After the Olympics I was doing my national service [compulsory military service] in the Army. An invitation came to ride the Route de France, which was the forerunner of the Tour de L'Avenir. It was a split team of 4 from the Army Cycling Union and 4 from the National Cycling Union. When we went over there [to France} we were like little lads amongst big men. We each had a couple of pairs of shorts and no equipment, nothing, really. But we got through, we really got through the race. That's how I really got the bug, if you like.

CB: Got infected, did you?

BR: Yes, that's the word.

CB: As an amateur racer in the 1950's what was racing like? Were there prizes sufficient to cover the cost of racing? Did the clubs support you?

BR: No... oh, no! Like I said, we were limited to airfields, trading estates [industrial parks], off-road, if you like, on macadam.

CB: It was for the fun of the sport, nothing like the continentals had?

BR: Oh... if you got 10 quid, you were lucky. You spent money to go to races. No doubt about that. There was no way you could make any money.

CB: So as an amateur you had to work in your father's business and find time to train before and after work?

BR: That's correct. I had to put in my forty-six and a half hours in of work and then train after that, in the evenings.

CB: You were doing construction work?

BR: Yes.

CB: Oh, my! You were training yourself into being an Olympic-class athlete and doing construction work at the same time? I can't think of a harder way to get where you got!

BR: [laughing] Well, it made things easy, afterwards.

CB: So later, all you had to do was chase Charly Gaul up a hill?

BR: Yes,... it just a pleasure...but... not when he put the hammer down!

CB: Did you travel to distant races or were you forced to stick to local races?

BR: Fortunately my father was in business with a small wagon, a small cabriolet, if you like. We could borrow it in the summer if we repaired it during the winter. That's how we got about.

Very often we would ride. The best event was in Birmingham, which meant a 90-mile ride. So, we rode the 90 miles on Saturday. It was in a pubic park and we had to be out of the park by 9:30 in the morning. So the race started at 6:00. So you rode the race and rode back home. That was a good training weekend, wasn't it?

CB: Yeah, that'd break my legs.

BR: That's how we came on stream. And of course, the Tour of Britain took off.

CB: You were, what we call drafted into the British Army? Did you end up on an Army cycling team?

BR: Yes, it was because I was reserved for the Olympics. The Army rule was that I couldn't be sent abroad until the Olympics were over. We managed to join up with 3 or 4 others and run a training camp.

CB: So you were able to keep your form...

BR: That's right. We raced in the Army events and in the RAF events as well.

CB: That's how you ended up in the Route de France, as you mentioned? [Robinson was fifth overall but lost time in the Pyrenees and finished40th]

BR: That's right.

CB: Was the climbing in the Route de France your first run-in with the big Cols of the Continent?

BR: It was my first big race. I think the Pyrenees are just as hard as the Alps. The grades are not as steady in the Pyrenees. It's more like a set of stairs instead of a long gradient. In the Alps you can settle down into a gear....get the right gear and you came come to the top in that same gear. But with the Pyrenees, it's a bit different. The gradient will ease and stiffen.

CB: So you can't find a climbing rhythm in the Pyrenees?

BR: No, you can't find a rhythm in the Pyrenees like you do in the Alps.

CB: I mentioned the rival licensing organizations. It's hard to get a full understanding after 50 years. Was it poisonous and discouraging to the riders?

BR: I wouldn't say it was poisonous. There was a great rivalry, but not poisonous, no. That didn't come into it. But if an NCU club met a BLRC club on the road, you can imagine what happened, couldn't you? Each would want to beat the other guys. It would be better than a race, really.

CB: Your brother Desmond was pretty good, wasn't he?

BR: Yes, he was, as an amateur. He never turned pro, unfortunately, because he took a different path in life. He got married and had children. That was a handicap, really.

CB: Did you feel early on that you had what we would call the genetic gifts for the sport? Did it come to you easily?

BR: Not at that time, no.

CB: You developed slowly?

BR: I think I was a slow developer, really. When I first went to join a French team, they said, "You're too old." I was 24 and had to start learn the business.

CB: Let's take a 1952 bicycle that you would have had. I assume the frame would be hand-built Reynolds 531 from one of the local builders?

BR: That's right.

CB: Did you have a favorite builder?

BR: No... My favorite builder would be the guy who would give me a frame.

CB: What other kind of equipment, cranks, brakes, hubs, etc?

BR: Let me go back, it was a British manufactured derailleur... Cyclo. It's Campag, Simplex now, but it was the British Cyclo gear that they gave us. Simplex was around. The Simplex was the better gear, actually. I remember "GB" brakes. That was from a guy named Gerry Burgess who made brakes.

CB: And what kinds of hubs?

BR: Airlight. Airlight were the best.

CB: And you were using tubulars, of course.

BR: Tubulars, yes.

CB: Aluminum or wooden rims?

BR: Aluminum. The wooden rims went out at the end of the war. There were a few who used the wooden rims because that's all there were, but when the new ones came, it was all aluminum. In my lifetime it's been all aluminum [aluminium]. The only time we saw wooden rims was in Paris-Roubaix sometimes.

CB: Magni used them for Flanders in 1950, I think.

BR: Yes.

CB: What led up to your being on the 1952 British Olympic Team? You must have been having real success in your racing?

BR: Yes. I was fortunate, really, being the youngest member of the team. Having a brother 3 years older I was included in their training bashes and training camps. I ended up sort of in advance of my age so far as a program of training went. I suppose that stood me in good stead. I was automatically included in all the big races.

CB: And so the Olympic selection committee chose you because you were a successful rider?

BR: Well that was always a problem with the selection committees, being based down South [Robinson is from Yorkshire, in the north of England], we always felt they favored the Southerners. It was the first time the Olympics had selected 2 brothers. So we felt quite proud, really.

CB: As well you should. You and your brother raced the 1952 Olympic Road Race in Helsinki and you finished 27th out of 112 starters and your brother finished right with you. A young French racer whose path would later cross yours finished ahead of you, a Jacques Anquetil. Were you aware of him then?

BR: No, the only guy I remember is the guy that won it

CB: How did the race go? Anything stick in your mind?

BR: Not really. It was a long time ago. I was quite happy to stay with the bunch, we were racing with the world's best. The guy who won it was a Belgian, Andre Noyelle. He's passed away, unfortunately. He had cancer a couple of years back. We see his wife every December. He beat the bunch by only about 50 yards, but 50 yards can be a gold mine, eh? He was a nice guy. Our careers crossed several times after that, of course.

CB: And then that Fall you got 8th in the World Championships?

BR: Best as I can remember

CB: 1953, the year after the Olympics. You were racing in Britain? Any trips to the continent? Any notable wins or losses?

BR: I raced in England most of the time. And then the Tour of Britain came along.

CB: Nothing in particular sticks in your mind from that year?

BR: I turned independent that year, so I couldn't ride the [amateur] world championships. An independent was in-between being an amateur and a pro. You could go back and become an amateur if you never turned pro. Yet, you could also take the prize money. Which being in the army, I weren't very well paid, so I needed little bit extra.

CB: So you're still in the Army in 1953?

BR: Yes, I came out of the Army in the end of '53. I was in the Army in 1952 and '53. I was riding as a sort of individual. There were 2 big teams at the time, Hercules and BSA. Every time we got into a break, we'd be with at least 3 or 4 of these other guys and they'd carve you up at the end. So I had trouble winning. The only time I could win was in my own country here, which is hilly. I could say, "I'm going now fellows, Good-by." Otherwise, if it were a straightforward race that was fairly flat, I'd no chance of winning it at all.

By the end of 1954, I got so fed up with this situation, I said, look if I don't get a place on one of these teams next year, I'm just giving it up. I've had enough. I ended up getting offers from both teams. Hercules was the one I chose.

They'd decided to mount a team to go to France for the following year {1955]. To me, this was like a present from heaven.

CB: You had a friend and fellow racer named Jock Andrews. Can you tell us his plan for the 2 of you to travel to races and the unusual transportation and sleeping arrangements?

BR: Yes, that didn't involve me. Jock and several others used an ambulance as a caravan [RV] to travel to races. They were centered in the Troyes area in France.

CB: 1954. You came in second in the Tour of Britain to a Frenchman named Tambourlini?

BR: I had the jersey for 4 days and they hammered me on the last day. They didn't bear with tradition and decided to attack me on the last day. A guy named Thomas from the BSA team [Thomas, nicknamed "Tiny Thomas"] won it the year before, in 53.

CB: Sort of like Robic in the '47 Tour de France?

BR: Yes.

CB: Even in 1954 were the prizes still negligible? Were you getting any support from shops or builders?

BR: I think I made about 80 Quid [Pounds] out of the Tour of Britain. And I'd had the Yellow Jersey for 4 days. So I must have been riding pretty well. So it wasn't a lot of money, really.

CB: Hardly enough to sustain a living and cover the expenses of traveling?

BR: Well, I was in the Army, so I always had a bed to go to. Even if the food was a bit poor.

CB: So, in 1954, you are listed that year as riding for Hercules and Ellis-Briggs. Is this right?

BR: Ellis-Briggs for most of the year. Then I changed to Hercules in about September.

CB: Is that when you turned pro?

BR: Yes.

CB: What was the arrangement with these builders? Did they give you a salary or just a bike?

BR: Hercules was good. They paid a good wage. It was about twice the average wage a manual worker would get. And of course, they paid all the expenses, so the wage went into the bank. It was solid and good. It was a really good year.

CB: You attempted to ride the Tour of Europe?

BR: Yes.

CB: Was that an amateur stage race?

BR: No, it was a pro race.

CB: How was it riding with the big boys?

BR: Well, we'd gone down to St. Raphaël [in the South of France] in the end of January and we trained with the Bobet brothers who were living in the same complex. Geminiani was not far away, so we had trained alongside the big boys. I felt quite comfortable, really. Jean Bobet [Louison's brother] spoke very good English so we got valuable tips from him. The first decent event was the Tour of Sud-Est where I took the leader's jersey....just for a day.

CB: A day, a moment, an hour or a week, you're still the leader.

BR: Yes, by steady riding, continuous good riding, the leader's jersey happened to fall on my back.

CB: This has to have been as fine a performance by an English rider since perhaps the turn of the century.

BR: Probably. To have taken a leader's jersey back then was unheard of.

CB: It's 1955 and British bike maker Hercules, which had sent you to the South of France had formed this pro team with the goal of riding the Tour de France?

BR: Yes, that was the ambition. Obviously you have to do some good performances to be invited to the Tour. It's not like that now, of course. I suppose we rode well enough to be invited.

CB: So you and the others in your team are in the South of France training and riding in early 1955? You were a bachelor. Was this a difficult thing?

BR: It wasn't a wrenching thing at all. It was an ambition fulfilled.

CB: Given the decent salary from Hercules with expenses paid, things were pretty good for you?

BR: It was heaven. If you wanted to ride your bike and get somewhere it was an opportunity from heaven. I don't think half the other people there appreciated that because they'd been with the Hercules team for about 5 years, enjoying all the benefits of a big company and they'd got a little bit slack.

CB: Whereas you were young and hungry?

BR: I was hungry. I was hungry and willing to learn I wanted to do this like the pros. That was an advantage.

CB: You got 8th in Paris-Nice.

BR: Paris–Nice is a real preparation race. It puts you on form for Milan-San Remo and the Classics.

CB: Did you find yourself like stage racing or did you prefer the Classics?

BR: Stage racing, definitely. Well, it wasn't so important that year. But in the following years when we were a lot poorer, it was far better to ride a stage race because you were looked after. The hotel bills were paid, your expenses were paid. So, it was far better to ride a stage race than a single day race because you didn't get paid for those. Also, I felt far more comfortable in stage races.

CB: We'll leave your most famous moment at Milano-San Remo for later. You got 60th your first time out. That was a long race. What was riding La Primavera like in 1954?

BR: Oh..1954, I'm not sure.

CB: Today the sprinters are almost impossible to drop on the Poggio as the pack zooms up in the big ring. The domestiques are so good they don't get dropped. Did you use the big ring back then?

BR: We didn't go up the Poggio. We finished on the Via Roma but The last hill was the Capo Berta. And it was flat from there

CB: So it was a big, mass romp to the finish line?

BR: We, we escaped eventually. But the first time you ride Milan-San Remo it's like a circus. It's so noisy and there are so many riders, so much traffic, so many horns blowing. You've got to get used to that. It's like riding the Tour de France, really. You've got to get used to the atmosphere, the noise and everything else before you can be a success. I don't remember much about the race itself.

CB: They must have been sending you around Europe. You got 4th in the Flèche Wallonne?

BR: That's right. We rode most of the big races.

CB: You were good. You were really, really good! That's a big race.

BR: It is a big race, yes.

CB: Do you remember that race?

BR: Yes, because it was coupled with the Liége-Bastogne-Liége, held during what was called the Ardennes Weekend. You would ride the 2 separate races and you'd get a classification based upon the 2 races. I was flying on the first day. I was also flying on the second day. Unfortunately at the feeding station I missed my feed.

CB: So you were cooked?

BR: Not being too well experienced I should have stopped and grabbed it. I went on thinking, oh, well, perhaps someone will give me something. I was there with a dozen Belgians at the head of the race asking for a bit of food or a drink. All I got was a grunt.

CB: A Belgian grunt at that.

BR: They weren't going to give me anything. Eventually I just blew up and that was sad, really. I was riding well and could have done something.

CB: And with the 4th in the Fleche the day before, you must have had really good legs?

BR: Yes, I was going well at that time.

CB: The British bike builder Hercules all-British team of riders did ride the Tour de France. Only you and Tony Hoar [who was the Lanterne Rouge] finished. You 2 were the first Englishmen to finish the Tour de France?

BR: That's right

CB: What was that first Tour for you like? What were your goals?

BR: Our goal was just to finish.

CB: Was it harder that you anticipated? Was it harder than the other races you had done that year?

BR: It wasn't the race itself that was so hard. It was the conditions, like the noise, the number of people. You'd be going up a climb and they'd be shouting in your ear. You'd be deaf. You've got to contend with these things. And when you're struggling it seems twice as bad. The first Tour was part of the learning curve. You'd get to each day's finish and think, "I wonder if I'll get through tomorrow's stage."

CB: This Tour, to me, seems interesting because of the intensity of competition the Swiss brought to the race. From your standpoint, did you sense this intensity?

BR: No, we were too busy surviving our own little war.

CB: The 1955 Tour did set a new record for the speed of the Tour.

BR: Yes, and it made us struggle even more. We were really busy surviving. And we didn't have a good command of the language at that time.

CB: You weren't fluent in French yet?

BR: Yes, still learning.

CB: You raced Louison Bobet at the peak of his powers and you knew him. Any lasting impressions?

BR: Yes. He had tremendous courage. He didn't have the class of Anquetil, for example, he didn't have the style. He was like the rest of us. He had to work at his job. It didn't come easy for him. I've seen him cry on his bike because he had been struggling so much. Now, I've done it myself, but he was a champion. I have great admiration for Louison. He wasn't particularly over-friendly. He always kept his distance. In French they say he played il a joué la vedette [he played the star]. He was always polite and did his job.

CB: How about Kubler, winner of the 1950 Tour? He was in the twilight of his career at this point.

BR: Oh, Ferdy was a comic. [Brian starts laughing] I remember getting to the top of the Ventoux with him. [stage 11 of the 1955 Tour] I caught him on the top, about 50 meters to go to the top. He's shouting to the crowd, "Poussez Ferdy, Poussez Ferdy! [push Ferdy]". He shouts the same thing in my ear. I tell him, "Ferdy, you can go to hell."

CB: He was asking you to push him?

BR: I don't know if he was asking me to push him or not, He was asking the crowd to give him a push. We went over the top together. I thought, "Right, I know this fellow can go down hills. I'm going to follow him." Which I did and it was my first lesson in really descending.

CB: Because Kubler was a very skilled descender?

BR: Oh, yes. I thought, I leave him at 30 or 40 yards in front and I'll manage to hang on and it was really my first lesson at going downhill. Eventually I got a reputation for going downhill.

CB: You ended up beating Ferdy by 10 minutes that day. Bobet won the stage. You finished with Jean Dotto and Jesus Lorono and ahead of Stan Ockers. You were in very fine company.

BR: It blew wide open that day. Yes, I had reasonable day.

CB: Every other boy in the world with a bicycle could only dream of finishing a Mt. Ventoux Tour stage with Lorono [KOM 1953 Tour] and Dotto [55 Vuelta winner, 4th in 54 Tour] and 2 minutes ahead of Stan Ockers [2nd in 50 and 52 Tour] and Raymond Impanis (Paris-Roubaix and Flanders winner] in his freshman Tour.

BR: They were the big names, weren't they, Ockers, Dotto and Impanis?

CB: You raced at a time when there were so many riders who were not only great champions; they were interesting and highly individualistic. They had personalities.

BR: That's true. Riders were free to do their own thing, up to a point. Not like nowadays when a team is engaged to ride, for example, Lance Armstrong. Back then, you would, obviously, protect your leader. But if there were an opportunity to go and do something, you were free to do that.

CB: Do you mean that team discipline has be come much more rigid now?

BR: I think so. The director has much more control now with his radios, etc. on the course. For example, [back in the 1950's] if there were some sort of jam on during a race and somebody got away, the team director would drive up into the bunch, seeking his riders. You would recognize his klaxon. You would automatically go to the front of the bunch so he couldn't get to you. The first guys on his team that he caught, he would chastise them and say, "Get a move on, get going!" So if we never saw him, we would avoid that.

CB: Hiding in plain sight?

BR: Yes.

CB: Velonews just published an interview with Pedro Delgado. Delgado thought that the direct control that the directors exert through their radios has dulled cycling. If a rider feels like he has good legs, he can no longer follow his impulse and attack. He has to get the approval of his director.

BR: That's right. We were free up to a point. You still had to be on guard if you were in a leading position. But on many occasions and if you weren't the leader of the race and if people attacked, you would go along and chase them. Now if that attacker were way down the line [in GC] and he was towing you along to a better [GC] position, in front of your own leader, well, that was allowed. So you were free up to that point, but you could not harm [your team's] situation, of course. The point being, even if you weren't the leader of the race, there were still opportunities, to win a stage or creep up the General Classification.

CB: So you believe the race radios and directorial control has taken away a lot of the...

BR: It's much tighter now. There is less opportunity for the rider to display his skill or enjoy himself. It's become corporate.

CB: More military?

BR: Yes.

CB: Did you know or remember anything about Jean Robic?

BR: Yes...[laughs]. I was responsible for eliminating him from the Tour.

CB: How so? Was it '55?

BR: No, It was Jean's last year, 1959. I was going quite well. I was ninth in General classification when we got to a place called Aurillac. Unfortunately, I caught or cold or ate something and spent the night on the loo. And of course, the day after I lost an hour. I was officially eliminated on time. But because I was still in the top 9 in the General Classification, they couldn't get rid of me. They had to keep me in the race. Which was fortunate for I didn't realize it. So, I was back in the race again.

So I won the stage at Chalon sur Saone [20th stage of the '59 Tour] and eliminated Robic at the same time because I won by 20 minutes.

CB: So your big gap left Robic with a huge deficit which was used to eliminate him?

BR: That's right. The headline was, "Eliminated by an Eliminae". He wasn't happy, wasn't Jean.

CB: And of course, Koblet did you see him ride? I've always read that he had a beautiful, effortless style.

BR: I rode with him. He was one of the few who rode a bike as if it weren't there. He just flew along. Obviously he didn't, but he made it look that way. I mean, every professional has to make it look easy, in order to baffle the opposition. Koblet was the pédaleur de charme. He just had style, really.

CB: Even though by this time, 1956, he wasn't nearly the rider he had been in 1950?

BR: Well my first year was his last year. I joined his team to ride the Tour of Spain with him, but he barely rode the race. [Koblet abandoned Vuelta on the 11th stage].

CB: You trained and raced in the South of France. Did the great Italians of the age race with you? Magni? Coppi, Bartali?

BR: No...I rode very little with the Italians. It was always with French guys.

CB: How about the Belgians? Van Steenbergen, Ockers?

BR: No, I didn't ride Belgium, to be honest. I knew them because they raced in France and I did ride the classics in Belgium.

CB: After the Tour, Hercules folded the team, apparently unable to finance the burden of a pro team?

BR: That's right.

CB: What did you do then? Stay in Europe? Go home?

BR: I went back home for the winter and returned to France in January. I went down to the south of France and commenced training as is normal in France. It snowed for 3 weeks. We didn't ride bikes for 3 weeks. This was a disaster because we had only enough money to spend a month on the Côte D'Azur. We'd hope to get some racing in and make some money. But that didn't happen. So I came back home at that point and sold the car. I said I'm going to have one last crack! I went back again and managed to link up with a guy named Raymond Louviot, who was a budding director sportif. He didn't have a job either. He was looking for a company that would give him employment. He got one or two hopefuls like me together; Swiss, Austrian, French and put us in as a mixed team in various races. We managed to get into the Tour of Spain. I finished eighth. That placing really got me onto the wagon. We didn't have sponsor's jerseys, we were just a mixed team of guys who rode under our own steam.

CB: At this point did you have an agent?

BR: No, no. I was just a free-lance, trying to get a penny any way I could. Eventually I made the grade and got involved with Daniel Dousset, but that came later. We didn't call them agents, we used the term manager.

CB: So you were with Louviot. ....

BR: We both got a job with the company call St-Raphaël, which is a French drink company. I got in through Koblet, as a matter of fact. I was engaged after the Tour of Spain. The firm that sponsored him was Cilo-St-Raphaël. I stayed with them all the way. Initially they were Cilo and they became Geminiani-Gitane. But it was the same team, really.

CB: Back then weren't the teams national in character and limits were placed on foreign riders?

BR: Yes, I don't remember exactly what the limitations were, but the limitations were there. The fellow who took me on, Louviot, was one who brought in various nationalities. He was quite keen on Dutchmen. He was quite keen on me, really. He was a fellow who really promoted European teams.

CB: Now that you were on the Cilo squad, did you get a paycheck or was still what you could win racing?

BR: No.. No, there was no money in Cilo. I rode the Tour de France again that year and got signed on with Geminiani St-Raphaël and then I was on a salary.

CB: So when you were riding with Cilo and Koblet's squad you got a jersey and a bike?

BR: That's right.

CB: The usual high pay for a 1950's pro, a jersey, a sandwich and a bike?

BR: [Laughs heartily] Yes, that's right.

CB: So when you got 8th in the Vuelta and Koblet was almost nonexistant as far as you and your team were concerned, what did you and your team do? Did you go for stage wins? Were you the team leader since you were so high on the GC?

BR: No, no. It was every man for himself. Each man was trying to prove himself, to prove that he could ride a bike and therefore get a place on a team.

CB: Well, I guess 8th got their attention and then you got 9th in the Tour of Switzerland. You must have been on top of the world?

BR: Well, yes, I as quite happy that things were going well. I had broken through the ice. I was getting noticed.

CB: So is this when you got picked up on Geminiani's team?

BR: Louviot, who had been running this as an ad hoc team, got the job as director sportif with St-Raphaël-Geminiani and took me with him. And I stayed there all my professional life. This was the end of 1956.

CB: After your 9th in the Tour of Switzerland you got an invitation to ride the Tour de France?

BR: That's right, in the Mixte Team with Charly Gaul.

We stopped the interview here and picked it up again in April of 2007. Here is the second part:

Brian Robinson, Second Part

CB: You got an invitation to ride the 1956 Tour. Was this selection made by Jacques Goddet?

BR: Well, the selection would have been from the original Tour, the '55 Tour, the first one I rode. And then, of course, I rode in France continuously then. So, they [Tour management] would monitor the situation.

CB: They saw that you were a capable rider and therefore issued the invitation?

BR: Yes, they wanted someone for the Team Mixte, the international team. Sometimes they called it the Mixte team, sometimes the International team, with people like Gaul and the like [meaning riders from countries too small to have their own national team for the Tour].

CB: The race started in Reims on July 5. Before that start when did you get together with the team?

BR: It would be the evening before.

CB: That was it?!?!

BR: Yes [laughing], that was it.

CB: Was there any strategy discussed? Who would be the protected leader, etc?

BR: [long pause] Not really. When you are a professional, it all boils down to what's in it for you, moneywise. Charly Gaul's team [meaning the Luxembourgers who were Gaul's regular domestiques and were placed on the Tour team] wasn't prepared to share their loot with anyone else. So the general issue was that if a rider on the team punctured in the first 100 kilometers of a stage, whoever was around would stop and help. And after that, you were on your own. {laughs some more]. But you see, Charly Gaul had 3 other teammates, so he was OK, really.

CB: Since Gaul had just come off his brilliant last-minute win in the Giro, I assume he was the team captain? But he had only his 3 Luxembourgers as dedicated helpers?

BR: That's right. That's all he needed, really. He wouldn't worry about people like me, and I could quite understand that. A guy that wins the Giro isn't going to bother about guys like me and the Portuguese and the odd Dane or whatever. He's got his program. It was just unfortunate for him that it was national teams as against trade teams, of course. If he'd been in a trade team he would have had all of his team with him, and then, no problem. But the Tour then was run under national teams. And he was disadvantaged by being a Luxembourger.

CB: So where did that leave you? How did you plan to ride your Tour de France?

BR: As a free agent. Taking opportunity when it arose.

CB: You were Robinson riding for Robinson?

BR: Exactly!

CB: The first stage went to Liege. You got into the winning break with Swiss rider Fritz Schaer and your friend, speedster André Darrigade. Do you remember that stage?

BR: Vaguely. I have 1 or 2 pictures from it. It was in my favorite kind of country, up and down, you know. Not too hilly, but hilly, which is the countryside I was born in. I must have been on song. I don't remember how the breakaway occurred, who attacked, for example. We were found at 3 in front and managed to stay in front. And being with Darrigade, the French team would block from behind, and the Swiss team would do the same. I didn't have a team, so I didn't bother anybody. I wouldn't be a problem to anyone.

CB: When you were in a break with guys like this, were you taking the hardest pulls you can. Or knowing who you were with, did you soft-pedal a bit?

BR: No, No! You did you share of work. It's normal really. If you can be in the first 3, you're in the money. So you work and take your chances. Unfortunately, I was with 2 good sprinters, so I was going to be third, anyway. But that didn't bother me. Third for me was quite good, at that time.

CB: While you were riding did you have any plans or hopes to beat Darrigade in a 3-up sprint?

BR: Well... no. It would be super-ambitious of me. It would take a long attack. I've known Dédé, as we called him, for a long time. And even then, he was very experienced. He'd seen everything. Possibly, if I had attacked, I don't think it would have changed anything. Darrigade would have waited for Schaer to chase and Schaer would have waited for Darrigade to chase, perhaps. But we were flat out! So how do you go 10 kilometers an hour faster? It was a case of rush to the finish, really.

CB: And Darrigade won the stage?

BR: Yes.

CB: And you got third?

BR: And I got third. I was quite happy with that, really.

CB: A nice days work for the first day in the Tour?

BR: Exactly. A satisfactory day's work.

CB: What was Darrigade like as a rider? Geminiani said he was the greatest sprinter of his generation. He could climb fairly well in addition to sprinting?

BR: He didn't climb that well in the Tour, on the big mountains. If the hills were fairly small, sharp and short, if you like, he was fine. Darrigade was born in the flat country of France, around Dax and Bordeaux, although it was in reach of the Pyrenees. Now, if that affected his style of riding, I don't know. He didn't climb the big mountains well. He climbed them, and got over them within the time limit, and that was his ambition in the mountain stages. So he was never a threat to a leader.

CB: The next day into Lille broke up into lots of smaller groups. Was this a result of high speeds.

BR: Yes. The wind was behind us and I was undergeared, to be honest. At that time we had 52-14 on.

CB: It just wasn't enough?

BR: No, although for everybody it was more or less the same. I think only Jacques Anquetil had a bigger gear on than most of us.

CB: What was he running?

BR: I think he'd be riding a 53-14. Most of the bikes were kept pretty standard for exchanging on route. So everybody had the same sort of gear on.

CB: Interesting that you finished in a group of 5 with Roger Walkowiak, the poor tragic Roger?

BR: Did I? [laughs] He never...never had any panache, never had anything like that. He would get lost in a crowd. If he were in a crowd you would lose him. Very strange, really.

CB: Gaul was in the group in front of yours, about a minute up the road. As I know now, you weren't trying to look after Gaul, he was sort of on his own.

BR: Yes.

CB: Gaul won the stage 4 15-kilometer time trial at Essarts. Were you surprised that a man so small could time trial so well?

BR: Yes he did. He pulled out the stops for a time trial.

CB: At the time were you aware of the prodigious quantities of drugs Gaul took?

BR: No. We were aware that it was around. But who was taking what, that was a mystery to us. We weren't in that sort of category, fortunately.

CB: So it wasn't general knowledge in the peloton at that time that Gaul was taking such huge quantities of amphetamines?

BR: No. Well I think everybody had suspicions. We'd think, "Blimey, how the Hell does he do that?" Nobody knew for sure...well at my level, we didn't know for sure. It was always suspicious. This is one of the sad things about cycling now. If anybody does anything extraordinary, drugs are involved now, aren't they. We all think so.

CB: They are involved just often enough to cause problems...

BR: That's right, yes, to quote the Landis case [Landis' arbitration hearing in Malibu, California was going on as this interview was being conducted].

CB: The stage 7 break of 31 riders gave Walkowiak the Yellow Jersey, taking it from Darrigade. Back in the pack were you aware of anything important going on up the front, since these were the days before earphones?

BR: We had what they called the ardoisier, the motorbike with the chalkboard that gives you the information on what's happening in front.

CB: And that's the only way you get it?

BR: That was the only thing that was up front.

CB: I noticed that in the Pyrenean stage you either finished with Gaul or just a couple of minutes behind him. After Gaul, I assume you were the best climber on your team?

BR: Yes, probably. Well, among the Luxembourgers, yes. I think I was eighth in the Tour of Switzerland with the Luxembourg team. So, yes, I would be the second-best climber, probably.

CB: In those days, were there much tighter restrictions on when you could get bottles of water?

BR: Yes, yes. During the section of feed, which would be 2 kilometers long, you could hand a bottle up. But that was it.

CB: You couldn't get a bottle from the follow car?

BR: No, not at all. Not from any of your team helpers. You could get one from a team rider, yes, but not from a team helper [meaning non-racing support staff]. Otherwise, you'd get fined.

CB: In the Alpine stage to Turin, you were spectacular, finishing with Gaul, Ockers and Walkowiak. Some riders break down during the three-week race and some, like LeMond and Ullrich, get stronger with every passing day. Were you one of those lucky riders who got stronger in a Grand Tour?

BR: I would think so. I recovered pretty well. I used to like stage racing as against single-day racing. I rode all the stage races I could.

CB: And your body thrived on it?

BR: I wouldn't say thrived on it, but I survived better than most. I had good powers of recovery, which you have to develop. You've got to get back to the hotel first; you get on to the message table first. That meant you had longer to recover before the start of the next day.

CB: At the time, were you aware of team director Ducazeaux's strategy of having Walkowiak relinquish the Yellow Jersey and then slowly recapture the lost time?

BR: I don't remember being aware of it as such. Whether it was a proper plan or...

CB: Did they make up the plan after the race?

BR: Exactly. I think that would be more like it. You take it as it comes in the Tour. He wasn't in a big team, so they weren't controlling it at all. It was a matter of taking the opportunity when it arrived. The guy who was second to Walkowiak, [Gilbert] Bauvin, was a teammate of mine [during the rest of the season]. And he was very adept, very quick-thinking guy. And he probably took more of the direction of the race than Ducazeaux.

CB: You'll have to forgive me for belaboring this particular Tour, but it fascinates me. Marcel Bidot, the French team manager thought that if Darrigade had surrendered his Tour ambitions earlier (he had been trying to win the General Classification for a long time during this Tour) and had been willing to ride for your friend, Bauvin, Bauvin would have been able to erase the 85 seconds that separated Bauvin from Walkowiak. In other words, if the French National Team did not have split ambitions, would Bauvin have won the Tour, in your opinion?

And Darrigade was reluctant to ride for Bauvin?

BR: Probably not. Probably not. They both rode for the same trade team. I don't know how they would have worked that out. [He asks me to remind him what mountains were included in the 1956 Tour. I give him the hair-raising list that included the Izoard, Aubisque, and the Croix de Fer].

Oh, we had a few there, didn't we? Well Darrigade wouldn't perform over those.

[Regarding Darrigade's reluctance to give up his GC ambitions] You see, there is a nice day's wage when you're carrying the Yellow Jersey, isn't there?

CB: And it's hard to give up.

BR: And it's hard to give up. You see, that's what pros race for, money. And also for Darrigade's own palmares, wearing the Yellow Jersey for I don't know how many days. It all counts, doesn't it? It all counts when he comes to sign his contract at the end of the year.

CB: You finished 14th in the Tour, up from 29th the year before. Things were looking up?

BR: That would be the best Tour I rode, best finishing position.

CB: How did the Tour leave you? Tired?

BR: It wasn't the Tour itself. The Tour was fine. It was the Tour and the "after the Tour". We rode roughly 30 rides in short of 40 days.

CB: These are the post-Tour criteriums?

BR: The criteriums. That was where we made our money. But some of them were 500 miles apart, you know, the next day. There was a lot of traveling involved. By the time that was over, I was knackered, really.

CB: Because of all the criteriums and all of the traveling?

BR: Well, yes. And I had raced everything from January 15, when we started training, right through to the Tour. And some of them, like the Dauphine and the Sud Est were stage races. So I'd been busy all that time. I suppose there was a little bit of, "I've made my season. That's it. I'm done, finished. I'm going home".

CB: So you went back to England over the winter.

BR: Yes.

CB: What did a 1956 pro do during the winter to keep his form? Did you worry about staying fit?

BR: Well, the last race was late September. I would come home and work in the winter, like digging trenches. My father was in the building industry. Used to go work for him, doing all sorts of bits and pieces, used that to keep fit, really.

CB: But the specific racing.....

BR: No, no. There was no racing. I rode my bike on weekends with the club and with my friends, that's all. I completely changed, did physical work, which improved the top end of your body. Because on the bike, you don't do that. On the bike your top end's static and it gets weak. So, in the winter you build that back up again. At least that was my theory then. It might have changed now.

CB: 1957: Now that you were part of a major pro team. You were now getting a decent, livable salary?

BR: Yes.

CB: So I assume that now, life is a lot better?

BR: Yes. I was taken care of. It was steady, regular and you could plan your season.

CB: Did you train by contesting the early season south of France races again?

BR: Yes, It was a fairly standard program, going down to Nice or San Raphaël on the Côte d'Azur, by the fifteenth of January. In fact, it was many a time organized by the team itself. They would organize the talent, there would be a soigneur with us. And the director himself would come down.

CB: So that's when you would meet with the team for the first time?

BR: Yes, late January or early February.

CB: It looks like a powerful team with Gilbert Bauvin, Miguel Poblet, Francois Mahe and Jean Mallejac, among others.

BR: Yes. We were the team that usually picked up most of the money in stage races, anyway. Not perhaps in the classics, but stage races, definitely.

CB: Who was the leader or the captain? Or were things looser then?

BR: No, they were a lot looser. You took the staff and sorted it out from there. They guys who were operating in the front, well they were protected, of course.

CB: OK, let's get to Milan- San Remo, 1957. You were in terrific early season shape, correct?

BR: Yes, yes I was. I had spent the winter digging.

CB: Do you want to just tell us the story, from the beginning, the one that got away?

BR: I was disappointed afterwards. During the race you do what you have to do and you think about it afterwards. I should have thought about it before that.

CB: During the race, you got away with 2 other guys?

BR: On the last hill, Capo Berta [this was before the Poggio and Cipressa were added], I attacked and got 50 yards.

CB: And you took 2 guys with you?

BR: No, they didn't come with me. I got a clear gap from [Miguel} Poblet. At the start of the race...there was something going on between Poblet and our team director, because he was riding one of our bikes. But riding in an Ignis jersey. I think our team boss was trying to get him into our team. So at breakfast table he said that if you're around Miguel at the finish line and you can give him a hand, then do so. Obviously, he was around me! It was the other way around. There we are. I attacked and Miguel shouted, "Hang on, Hang on." So I waited and Poblet and [Fred] De Bruyne came up to me. And then we rolled it then right to the finish. I said to Miguel, "What do you want me to do?"

He said, "Lead out, lead out." So I led out, you see, and that's what happened. You know the result.

CB: Poblet won, De Bruyne was second and you came in third.

BR: I could have been a bit sharper, I would have thought, "Might be able to do something here." But that didn't happen. So there. It's a regret on my part.

CB: Looking back on your career, is that the biggest race you wish you could do over?

BR: Oh, yes! That's certainly the classic I would have like to have won. That and Paris-Roubaix, of course. But Paris-Roubaix was not a race for me.

CB: But that was one you could taste!

BR: Yes, yes. I was there. I was what, 2 meters behind.

CB: Your early season seemed to bode well, with high placings in Paris-Nice and the Tour of Luxembourg but you didn't do as well in the 1-day Northern classics, which again confirms that you are a stage racer?

BR: Yes. I think I had a fourth, I think, that year in the Flèche Wallonne.

CB: That year you got your first pro win, the GP de la Ville de Nice.

BR: Ah, yes, right, beating Louison [laughs].

CB: Yes, you beat Louison Bobet by 50 seconds.

BR: Yes, left him downhill.

CB: Beat him by almost a minute!

BR: [still laughing] It was funny, because we had been training together, with Jean Bobet. Louison didn't turn up very often. Jean [Louison Bobet's brother] did because we were living sort of next door to each other. It was quite funny, really. I don't know if Louison thought it was funny, but I did.

CB: Well, he seemed to take things seriously.

BR: Yes, he was a serious guy. Jean was much more relaxed.

CB: For the Tour, you were again put on the Luxembourg/Mixte team. Did you view this as good or bad or just a way to make a living?

BR: Well, riding the Tour is great. Because if you can do something in the Tour your living is assured for the next year.

CB: So you take what they give you?

BR: Exactly. You are pleased to get a ride in the Tour. Definitely. No question about that.

CB: Your team leader, Gaul, abandoned on the second stage. The day was very hot.

BR: I don't remember that.

CB: Now this gets my baloney radar going because Amphetamines make things hard on a hot day.

BR: That's right.

CB: I think it was Bahamontes who said he loved a hot day because guys like Gaul couldn't handle it.

BR: That's right. Well I didn't mind the hot weather, I could cope with that. Mind you, I didn't like the cold weather.

CB: Stage 5 was a rainy day going from Roubaix to Charleroi. Anquetil's break held off the pack but you abandoned. I know the only way you would quit the Tour would be if someone tied a rope around your ankle and dragged you away.

BR: I broke my wrist. At the feeding station someone stopped smack in front of me. I went over his back and fell on my wrist. And then I started the next day, but it was impossible, really.

CB: And that sort of put paid to your season?

BR: Yes. It was just a mess after that.

CB: Let's go on to a better year, 1958. You must have become close to Raphaël Géminiani?

BR: Well, he was sort of my boss and a teammate, of course. And, I like to think, a friend as well.

CB: And you were riding his bikes?

BR: Yes.

CB: Did he own the team?

BR: No. The team was St, Raphaël, really. And Geminiani had sold his name to a firm called Gitane, who made the bikes.

CB: Who was the director?

BR: Raymond Louviot.

CB: He was still the director?

BR: He started his career as a director as I started mine as a rider and I never went anywhere else.

CB: Did Géminiani have any particular position in the team?

BR: Not really. He never had any sort of authority above the team director, who was the boss.

CB: Was Géminiani as much fun to race with and be around, as he appears to have been?

BR: Oh, yeah. There was always something happening when Gem was around. He was a noisy guy, he always had a good shout. I suppose his origins are Italian. He was always good fun.

CB: In 1958 you must have been in fine form early on, having been the King of the Mountains in Paris-Nice. You must have been in really good shape?

BR: I must have been. I could usually climb...not with the greats, not with Gaul, not with Bahamontes, but with the others, yes.

CB: And Géminiani came in third in the GC, so he must have also felt that the season augured well?

BR: Doing OK, yes.

CB: At this point was he expecting to ride on the French national team in the Tour?

BR: Yes.

CB: But of course, that didn't happen. He took his placement on a regional team for the Tour very hard. Did you ever talk to him about his exclusion from the national team?

BR: No. It was something sort of beyond me, involving personalities, Marcel Bidot [French Team manager], Darrigade and Gem himself, of course. Eventually they did get together, didn't they?

CB: Yes, but boy was he bitter about that Tour and being placed on a regional team, and he almost won it.

BR: That's right, he wasn't far off was he? [Géminiani was third, at 3 minutes, 41 seconds]

CB: You were no longer on Gaul's team, you were put on the "Internations" team with Seamus Elliot and an assortment of Portuguese, Danes and Austrians. Once again, were all just riding as individuals?

BR: Well Shay [Elliot] and I rode together. We rode and looked after each other because we were friends. If we were both riding the same race somewhere, we would travel together, in the same vehicle. We were good friends. We roomed together. The same thing operated. The first 100 kilometers, if somebody punctured, we would stop, but after that, you're on your own.

CB: What were the politics of Géminiani being on one team and your being on another for just the Tour. For that matter, I think Elliot was on Anquetil's team the rest of the year. Were trade team loyalties forgotten or were they always a hidden force in the Tour?

BR: They were always there. Obviously, you wouldn't cut your teammates up. And if you could get away with a teammate in an échappé, a breakaway, you would work together. Because at the end of the day the trade team, the jersey, got the publicity.

CB: It was always there?

BR: There was always a mixture of loyalties. I never had any loyalty anywhere else but to my trade team. I think the guys must have known that. For example, a guy who was on the French National team in my trade team would come and say to me, "We're going to do this today. Give us a hand, if you can." I was a free agent and by doing that sort of thing you get into a situation where perhaps you're in a breakaway or a thing that you can exploit a little bit.

CB: Because at the end, you guys are professionals and this is what you do for a living.

BR: Exactly.

CB: It's has been written that the era had a third set of teams, with the riders lined up according to their agents and that loyalties could cross trade or national teams if it could give a rider's agent more power in later negotiations. Was this true?

BR: This is a spin-off from the Poulidor-Anquetil war because both had different agents. I think fortunately for me, I had the same agent as Anquetil, so I was in the right group.

CB: So, you were covered.

BR: Yes. Daniel Duosset always had the best riders. It wasn't my decision. My team director said you ought to get this manager [the agent Dousset], he'll look after you, and that's what happened.

CB: So there was another level of protection for you?

BR: Yes. Being a lone Englishman, at that time, when they were making up an international racing field, that was thought of. Which was an advantage for me. If there had been 10 Englishmen, for example, I wouldn't have had half as many rides.

CB: OK, Stage 7 of the 1958 Tour de France, coming into Brest. You became the first Englishman to win a Tour stage. It looks like this broke apart and the front part of the race became fragmented. How did the stage go?

BR: I'm not sure why it broke up. I don't think there wasn't a terrific wind because I was never a good rider into the wind. So, it wouldn't have been exceptionally windy. I think it was just the fast conditions.

CB: Pressure of the speed and the aggression?

BR: Yes. And then, finding yourself on the right wheel at the right time. I don't remember who attacked and got the breakaway going, but I know I was riding pretty well. I must have done my share.

CB: And you finished with Arrigo Padovan and Padovan was declassified? He was relegated?

BR: That's right. It was a finish [made] for me. It was a long, straight uphill.

CB: Did he throw you a hook?

BR: I went on the left-hand side of the road and jumped. We were on the right hand side and I jumped across to the left and went. And he came across, on to me. About 200 meters before the line he got past and pushed me into the barriers and so I braked and went around the other side but just failed to get around him again. So, the judges gave it to me.

CB: Which is only fair.

BR: I think it was. I think I had the beating of him. Like I said, I came back up on him.

CB: And you 2 are friends today?

BR: Yes. I call him Bandito, "Hey, Bandito." Although I haven't seen him for a couple of years. He used to go skiing. He's dropped off now. Whether his health has gone by the way, I don't know.

CB: It looks like you were flying in the 1958 Tour. After a terrific first day in the Pyrenees, you had a wonderful ride over the Aspin and Peyresourde and finished with Anquetil, Geminiani, Nencini and Gaul with Bahamontes 2 minutes up the road. Did you ever get to know Bahamontes?

BR: Yes, quite well. We did a Tour in Spain, Darrigade, Anquetil, Bahamontes and myself. Going back to my day, cycling was pretty rough in Spain, unorganized. So we were riding around in stadiums and football fields on exhibition against the locals, which was a bit of fun, really. So I got to know Bahamontes quite well, that way.

CB: Was he as eccentric as they written about him or was that exaggerated?

BR: Oh, it was exaggerated like all things are exaggerated in the media. No, he was fine.

CB: He was a regular guy to you?

BR: Excitable, yes. A lot of the Italians are excitable as well?

CB: With such a nice ride, were you thinking really high GC at this point?

BR: I wouldn't imagine so. My thing was to slip into a breakaway get a wing on it if I could. There was no way I could get high on the classification with the team like we had, really.

CB: Help us poor mortals. When there is a group of immortals like Anquetil, Geminiani and you and Nencini in a break, guys that we read about in the history books, what's it like? Are you just a bunch of guys riding and racing bikes?

BR: Yes [drawn out for emphasis]. I think the thing about cycling is that we all suffer and struggle together and afterward, you're best mates. It's a bit like Rugby. You knock the hell out of each other then you go have a couple of pints together. We're all still friends today.

CB: Back then, in the Pyrenees, what kind of gearing are you using? Did you have a 42 up front?

BR: I used to ride 46-49.

CB: 46-49 up front. And what did you have in the back?

BR: I think it would be a 26.

CB: 1959: Your team had a new rider, Roger Riviere. Can you tell me what he was like? I understand him to be arrogant, dumb, and extremely powerful.

BR: I don't think he was the best of tacticians. I didn't have a lot to do with him because he was in a separate track. He was specializing in the Hour Record, and pursuits and time trials. And then, of course, he came along to the Tour because that's what all bike riders do in France. He was sort of protected by the management. He obviously had a fabulous future.

CB: You and Riviere went with Géminiani to ride the Vuelta. It looks like neither you nor Géminiani were able to finish and Riviere did the best on your team at fifth.

BR: It was a poor sort of race. I don't remember why, but we punctured galore for some reason or another. I remember one day I had 3 punctures, "What am I doing here?" But there we are. I just don't remember what the sort of real circumstances were. It's unusual for me to abandon a stage race. I don't remember why, to be honest. Probably didn't want to remember why.

CB: For the Tour, you are again put on a mixed team , this time of Brits, Danes and Pole, and Austrian and Elliot from Ireland. The French team was riven with the warfare between Anglade, Anquetil and Riviere. Riding for the Internations team did this affect you at all? At the time were you aware of this war that was going on or were you just riding your own race?

BR: We were aware of it, but it didn't affect us. You read the race as it happened. As far as my own personal riding, it didn't make a bit of difference, really.

CB: Did you know Henry Anglade?

BR: Yes.

CB: Reporters didn't seem to like him. Did the riders?

BR: Yes, I think so. Generally, he's well thought of. I meet him fairly regularly these days, twice a year. His nickname is "Napoleon", you know. He always spoke what he felt. Sometimes that doesn't fit in, does it?

CB: And I guess he was a terrific descender?

BR: Yes. Born in the mountains, he would be. And there again, it's another case of the wrong manager [meaning agent].

CB: He wasn't one of Dousset's riders?

BR: He was on Piel's list instead of Dousset's.

CB: You were in the thick of things in the famous Stage 18 that went over the Galibier, Iseran and the Petit St. Bernard and finished in Aosta. You were riding in the Anquetil/Riviere group. On the descent of the Iseran, Bahamontes and Gaul had mechanical trouble and lost contact with your group but it looks like Anquetil and Riviere let Gaul and Bahamontes get back on. They didn't try to distance themselves because that would have meant helping the other guy?

BR: [interrupting] ah yes, they had Dousset, yes...

CB: Was this because Bahamontes also had Dousset for his agent?

BR: [Laughing] Well, it's quite possible. I don't suppose I spoke good enough French, really, to understand all the details. You read the journals [newspapers] afterwards and you think, " yes, possible."

CB: And we get to stage 20, which you mentioned earlier when you caused Jean Robic to be eliminated. How did you beat the pack by 20 minutes?

BR: It was a member of our trade team, Gérard Saint, who was placed in the King of the Mountains [second to Darrigade in points and third to Bahamontes and Gaul in the KOM in the 1959 Tour. He finished second to Rolf Graf in the previous stage, a mountainous one with 4 major climbs] and he needed to protect his position or gain another point or 2 to keep his position. So he said to me, he knew I could climb, would I lead him out on the last climb, because he needed the points? I said on the condition that you sit up [at the crest of the climb] and let me go. It was the day before the main time trial, the big time trial. So, I got the mechanics to get my time trial bike ready for that day, the day before [the time trial], put light tires on it and everything, ready for a good session.

That's what happened. I led him out over the climb. He got his points and then I went off over the top of the climb. There's a guy called Jean Dotto, who was involved in my [stage] win at Brest.

I could hear him shouting behind, but Jean can't go down hills. I had to make at least a minute on the downhill to get away from the bunch. So that's what I did. I ignored Jean and went. I'm going down this hill on very light tires and there's gravel and all sorts of things and I thought, "Crikey, if I puncture now, it's all done." I got down the hill and I had 2 minutes at the bottom. They never saw me again.

CB: You just rolled away?

BR: I calculated that the big guys would be wanting an easy day because it was the time trial the day after. I was quite friendly with most people, I had no enemies. I'm not going to affect anybody. "Good luck," at least, I hope that's what they were thinking. That's what happened, really. So I just plowed a furrow to the finish. And quite happily, I put my hands up across the line.

CB: And threw poor Jean Robic out of the race?

BR: Well, yes, sorry about that. Strangely enough, our ski week was fixed up by Jean, the week we go skiing every winter. Unfortunately, of course, he's not there now [Robic died in 1980].

CB: You talked your team into signing Tom Simpson?

BR: Yes. But they already knew of his existence. They are like football managers. They have spies in the area. I had said to the director, "There's a good British lad coming up. Are you interested?"

He said, "Yes, get him to see us."

He was in Brittany when the Tour passed in '59. He [Simpson] came to the team hotel. Raymond Louviot signed him up there and then. And then he started the next year, of course.

CB: 1960. Roger Walkowiak joined your team, Rapha-Gitane. Today we read of him as an angry and bitter over the derisive reaction from the French pubic to his 1956 Tour win. Did he carry any of that when he rode on your team?

BR: No, he was a very private man. Like I said, he had no panache. He didn't talk, didn't come out with anything, really. I don't suppose I spoke good enough French to hold a really deep conversation, anyway.

CB: You never became fluent in French?

BR: Not fluent, no. I can hold a conversation. When it comes down to a real understanding, no I skim over the top, if you like.

CB: Let's move on to the 1960 Tour. This year you rode on a purely British team. This was Tom Simpson's first Tour ride and only you and Simpson made it to Paris?

BR: That's right, yes.

CB: Was this the first time for the 2 of you to extensively race together?

BR: No, he'd won the Tour of the Sud Est. I'd ridden that for many years, the Sud Est. It was a race I liked.

He came along, and he fell off. I don't know where, just where in the race, but he fell off. So, I waited for him. And he caught up. We were going downhill somewhere in the middle of France. I said, "Stay on my wheel and we'll get back." He did, but he fell off yet again. I said, "For Christ's sake, sit on my wheel!"

Anyway, we got back to the bunch and he won the race eventually. I don't know what happened to me, but he won the race. So, you see, it's never lost, really. You've just got to keep banging away.

CB: You read about how ambitious Simpson was, how driven. Did you sense this?

BR: Oh, yes.

CB: You could feel it?

BR: He'd do anything to win, as we well know now. The sad thing is, he didn't need it. He had it within himself. He didn't need to dabble with medicines.

CB: He had enough natural talent?

BR: Yes, I'm sure he had. He could cane himself so hard he'd just fall over and need oxygen to recover. Well, if you can do that, you're on to a winner.

CB: What were your plans for the 1960 Tour? Now that you had a British team, were you guys riding as a team?

BR: We would be, oh, yes.

CB: Did you have a leader, or was it, see how it goes?

BR: I should imagine Tom would have been the leader. By that time I was sort ready to take a back seat.

CB: This was an interesting Tour. I hope you remember the dirty details. Anglade got into a break on stage 4 and was in Yellow. 2 Days later Riviere drove a break that had Gaston Nencini in it to a 13-minute winning gap. Anglade had begged Bidot to slow Riviere down be cause he knew how good Nencini was, but Riviere wouldn't be slowed. Do you remember that day and the fallout?

BR: I remember it vaguely. I don't remember any details. It was criticized badly in the press.

CB: Anglade thought Riviere had handed the Tour to Nencini because Nencini was a more complete rider. Which happened, of course. Riviere tried to stick with Nencini and Nencini just went down a hill that Riviere couldn't follow.

BR: That's right. He [Riviere] wasn't a good descender, that's how he had his accident. You get a sense that with some riders, you'd ride behind because you are so confident that they'll not make a mistake. Well, Riviere wasn't one of those.

CB: While Nencini and Anglade were very skilled downhill.

BR: Yes! Particularly Nencini. I took lessons from them and those sorts of guys. I would think, "Well, he's not leaving me."

CB: If you get down with them, you gain a lot of time?

BR: That's right, and experience, as well.

CB: Simpson was doing well for his first Grand Tour. I assume you, as the old hand, was guiding and advising him along the way?

BR: Yes, I would think so. We shared a room together. We lived together, really. I passed on anything I could.

CB: We have to come to the tragic 14th stage of the 1960 Tour and the Col du Perjuret. Riviere had, as Anglade had predicted, been sticking with Nencini, planning to finish him off in the final time trial. Nencini took off on the descent of the Perjuret as only one of the peloton's finest descenders could. Riviere went off the road, crashed and broke his back.

Where were you when all of this was going on?

Any particular memories of the day, the helicopters?

BR: Yes. He must have been in front of me, because I passed the scene. You don't see what's happening at that sort of race, at that sort of pace. You don't get the results until afterwards, which was very sad, as we well know.

CB: Never to ride again.

BR: Well, he tried, but there was nothing there.

CB: It turned out that Riviere was stuffed with so much palfium and amphetamines that he couldn't feel his brake levers. Were you surprised?

BR: Well...Nothing surprises you, really. It's difficult to explain. You hear all sorts of tales of this and that. Take this and it'll do that. And somehow, I never got into that sort of school. Thank goodness.

CB: You never had to resort to...

BR: Well nobody ever came to me and said, "Look if you do this, you'll win that and this now." I must admit it would have been a difficult decision to make if somebody would have said that to me, "Take this pill and you'll win Milan-San Remo," for example. That would have been terribly difficult.

CB: So, you never had to resort to drugs?

BR: No. Apart from the aspirins and large doses of Vitamin C, which were administered by the Tour doctor himself. No, there was no problem that way.

CB: No, at that time, the drugs didn't have the same stigma they carry now, did they? Because, for some of the pros, it was just one of their tools.

BR: Well it seemed like it. Anquetil never denied it. In fact he admitted it.

CB: Coppi did.

BR: Coppi did, yes.

CB: Were you aware at this time of Simpson's drug use?

BR: Not definitely, I mean, we had a flat in Paris together for 1 season. I went off for a month. I used to go every month or every 2 months. I came back and he had moved out, to Belgium. And Belgium was the source of most of the problems. I thought, "There you go..."

CB: At some point you got married. When?

BR: I got married in London in...good question [laughs]...'56, October '56.

CB: Did you maintain a home in England or were you a transplant until the end of your career?

BR: Yes, the home was always in England.

CB: Did your wife travel back and forth with you?

BR: No, not really. In '56 we went over in a caravan and lived in a caravan for a season. So we moved about with the races with our caravan.

CB: Do you remember what you were making in 1960? Was it a comfortable living?

BR: I used to want to put 1,000 pounds in the bank when I came home in the winter. You can liken that to the price of a family car.

CB: Put a car in the bank?

BR: Which was OK.

CB: Were you enjoying your career? Did you enjoy what you did for a living?

BR: Yes, basically it was what I wanted to do. The publicity was quite good, as well. I suppose you get a little bit used to that.

CB: 1961. My, you won the Dauphiné Libéré!

BR: Yes, it wasn't a bad year. It was virtually my last, really.

CB: Was this the biggest win of your career, or are your Tour performances more important to you?

BR: It's different because in a race like the Dauphiné you've got your team around you. I never had a team around me in the Tour. It was always an individual event for me.

CB: So in the Dauphiné you got to race as a protected leader in a stage race?

BR: Yes, with good teammates around you, you couldn't lose. In fact, I think we had first, second and fourth, I think. So, we were pretty well placed.

CB: That must have been very satisfying?

BR: Very, yes. [laughing] In fact, on the last day I got attacked by the teammate who was second, which was Wolfshohl.

CB: Coming out of the Dauphiné, what were your plans for the season? How did you feel?

BR: It was to be the normal program as far as I was concerned. A place in the Tour is what you race for most of the year.

CB: You didn't have your normal Tour in 1961, coming in 53rd, 2 hours behind Anquetil. Did the Dauphiné empty your tank?

BR: It's quite possible. To be honest I don't remember much about that Tour. I don't think there were any highlights. I was sort of thinking about winding down that season. Now whether the win in the Dauphiné put that away for a while, I don't know.

CB: It looks like the final stage from Tour to Paris was anything but a promenade. It broke up into several groups with Anquetil in the first break. You were with Guido Carlesi, in another group, who used the gap to gain just enough time to move up to second place in the GC and bump Gaul down to third. Was Gaul asleep at the switch or did he not care about second place?

BR: I think they caught him napping, knowing Charly. I mean everybody would have thought it would be a promenade and they must have caught him napping in the wrong group. And he wouldn't have had a team strong enough to get him up, by that time in the Tour. His team would be all knackered

CB: And Carlesi would have a good team, of course, the Italians.

BR: They must have planned that. I should have imagined that the Italians with Alfredo Binda, would have planned that.

CB: Gaul would regularly bleed enormous amounts of time early in Tours and then wait for a killer mountain. Was this due to inattention or confidence? Do you know?

BR: He didn't like flat stages. So I don't suppose he would tire himself too much on the flat stages. I suppose he had the confidence that, "I can take back 10 minutes, anytime in the mountains." Which, of course, he could. Until he came across Bahamontes. I would think a little bit of laziness, if you like.

CB: 1962. The name of your team changed to ACBB-St Raphaël-Helyett. You got Anquetil, right?

BR: I never raced with him at all. I wouldn't take on another team director, I would retire. I retired then.

CB: So you didn't go to the Tour because you had retired. You had hung your chamois up?

BR: I did. I hung up my wheels for a while as well.

CB: Can I run the names of a few of the great riders of the 1960s and get your impressions?

BR: Yes.

CB: Raymond Poulidor. Did you know and race him?

BR: Yes, in his early years.

CB: Friendly, nice, powerful?

BR: Yes, he's a gentleman.

CB: Rudi Altig

BR: Rudy was a little bit special. He was a gentleman, but I think he had a mean streak. Probably a good mean streak, which you need to win bike races.

CB: Like a boxer has to be a headhunter?

BR: Yes.

CB: Did you race Rik van Steenbergen?

BR: Yes, I did. He spoke a little bit of English. That's how I got to know him a little bit. He wouldn't do the dirty on anybody. In fact, later in life he married a girl from 40 miles away from me. I used to like Rik and I admired his career. He rode everything, 6-Days, Tour de France, Milan-San Remo; everything there was to ride. Never went out training. Just raced.

CB: Just a natural athlete?

BR: Yes.

CB: How about Rik II, Rik van Looy?

BR: Didn't know him very well. Rik II had a certain reputation, but he didn't bother me, anyway. He wasn't in my sort of racing.

CB: Was retiring something you had planned upon for some time? I talked to Franco Bitossi. He and Gimondi were racing in the rain and they just said to each other, "We're done." And they both retired on the spot. They quit, right there. They both said that this was the right time for them, they had enjoyed long careers. How did you know when it was the right time?