Ride Like Fools, Eat Like Pigs, or,

A Cyclist Revisits Beautiful Italy

by Chairman Bill

"Mauro, do you want to do another little giro of Italy, like we did in the Spring?"

"Yeah, sure."

When I saw Mauro Mondonico (son and apprentice of the famous framebuilder, Antonio Mondonico) during my last visit to the Milan show in the Fall of 1998, I asked him if he would like to accompany me on another riding, eating, and art viewing trip of Italy. I didn't know exactly how much he would want to repeat a couple of weeks of close living with me, but he is a tolerant sort. He accepted my invitation immediately and with enthusiasm. We were on.

What follows is the story of my 1999 Spring cycling trip to Italy with my dear, wonderful wife Carol, Mauro, and good buddy Terry Shaw.

Last year we chose three cities, Pisa, Assisi, and Siena. We spent two or three days in each town, riding big, long loops in the Tuscan and Umbrian countryside. If the reader has an unquenchable thirst for either my deathless prose or overlong stories of cycling, click here for the story and pictures of our 1998 trip. We learned a lot last year, and intended to profit from that knowledge.

The first thing that we did wrong last year was in choosing Pisa. It is too big. Too much time was spent getting in and out of the city. Trying to leave town, we got lost more than once. Escaping the big city chews up those precious few hours when you want to be out in the country, riding on lonely roads, breathing clean air and listening to the birds. Also, the roads outside of a big city, once you have escaped, have much more traffic, so it is doubly hard to get away from the noise and bustle.

For this trip, I made a list of all the Michelin Green Guide two and three star cities (one star: "interesting", two stars: "worth a detour", three stars: "worth a journey") in Tuscany, Umbria, and The Marches ("Le Marche" in Italian) that had populations less than 25,000. I cut the list apart and taped the pieces of paper on two big "Touring Club Italiano" road maps laid out on the floor. By the way, anyone considering a driving or riding trip to Italy should use these maps. They are the best, most detailed maps of Italy you can get. They can be tough to find (stores specializing in foreign maps have or can order them).

Then, between shooing our cats off the maps, we could see which cities had the best possible combination of cycling-friendly roads, art, and tourist amenities. We settled on Volterra in Tuscany, Orvieto in Umbria, and Urbino in Marche (near San Marino). Last year we chose towns that were strong in pre-renaissance art and culture. This time, our cities did not have a particular theme. Each had its own unique appeal. More about each city later.

One problem we had to solve was making the trip more fun for my wife, Carol. She no longer cycles even though she has seen more of the U.S. by bike than I probably ever will. The trouble was that Carol wanted to be at the hotel when we returned from riding so that she could go eat lunch with us. Not knowing when we would come back sort of confined her to hotel jail. Very unfair to her. Mauro and his brother Giuseppe solved that one. Giuseppe lent Carol his cell phone. Mauro, being a true Italian, is never without his, so Mauro could keep Carol informed of our whereabouts and give her the freedom to tour as she pleased. For the readers that do not have a generous friend with a generous brother, cell phones can be rented in Italy at the airports, or in the states before leaving.

I booked the rooms, making sure that each hotel had a good, big breakfast, and that each would allow us to check out a bit late. Checkout times last year cut some fine rides very short. We found almost all the hotels we contacted very accommodating on both these concerns. Be sure to get these details settled in advance, however. Italian hotels are very reluctant to allow a late checkout when permission has not been given ahead of time. You have no leverage with the hotel when you ask to leave late on the last day. Your bargaining power is strongest when you are booking the room.

Normally, I am not a gambler. But in the case of the timing the trip, the costs bring out the risk taker in me. Airlines have either two or three prices for transatlantic flights. Winter is the cheapest, being about $525.00 round trip from Los Angeles to Milan. Sometimes there is a shoulder season at about $800.00 and high season at about $1,000.00. We booked the last cheap winter flight to Italy, March 24 (Alitalia charged $1,050.00 for March 25 tickets). The weather in Italy changes at the end of March, but exactly when Spring decides to show up is a fact known to no one. The possibility of bad weather is the risk I chose.

So, we were off. Terry Shaw of Shaw's Lightweight Cycles in Santa Clara, California had expressed a real interest in coming along. Well educated, with a love of bikes that borders on the insane, I knew he would make a fine companion.

Off to Italy. Mauro was at Malpensa airport (Milan) waiting for us with a van. I think one of the greatest luxuries an air traveler can have is a friend waiting at the gate. No trips to parking garages, no shuttle buses. You're just gone. But wait, a surprise. Waiting in another van was Antonio Mondonico. Any day that has the kind, gentle Antonio in it is a better day.

Our first stop was a visit to the Vittoria shoe factory. Carol and I had taken on the American distribution of Vittoria shoes in the fall of 1998, but had not yet had a chance to watch the shoes being made. Also, Vittoria's owner, Celestino Vercelli, was a pro in the 1970's riding for the powerful SCIC team. I wanted his advice on a few roads, knowing that there were few roads in Italy that he hadn't ridden.

We pulled up to the small factory building. I think workshop would be a better word. Celestino, a big bear of a man with a genial yet authoritative presence, greeted us. His son Edoardo made coffee for us and we talked a little of business and more of the important job of riding. I had thought of one particular road for inclusion in the first day's riding near Lake Como. Celestino warned us away from it. He said that even the pros didn't enjoy it. Never mind. Not for the first day, at least.

From Vittoria, we went to Mondonico's home and workshop to assemble our bikes. This time I brought my baby, my Campy Record equipped Torelli Nitro Express. Earlier, I told Carol that I was going to bring my Athena/Super Countach because I was afraid of what traveling would do to the Nitro. Carol stopped me cold. "You're going there to enjoy cycling. Why don't you really enjoy it? Bring the bike you like most." That settled it. The baby came. It took just a few minutes to get it assembled. Then Mauro and I decided the next morning's ride. From Concorezzo near Monza to Como, up to Bellagio, down to Lecco and home. It should be spectacularly beautiful once we got to Como.

But, Mother Nature wanted to be sure we knew that there were sharp claws concealed in her hands, and that she could use them.

March 26, Friday

After demolishing the hotel's buffet, we called Mauro to be picked up. At the shop, we agonized over what to wear. It was 8 degrees Celsius (47°F) and lightly raining. I wore two layers of wool and shorts and a plastic rain jacket. The others about the same. At the time, it seemed more than enough for the hard riding we planned. We rolled out of Concorezzo towards Como. I think the traffic in Lombardy (the district around Milan) gets worse every year. Even though Italian drivers are extraordinarily courteous to cyclists, the narrow roads with big trucks are not to this small town boy's taste.

With legs made sodden with jet lag, we started slowly, riding by the huge park of Monza and then northwest to Como. As we descended into Como I heard a noise I had never heard in all my years of riding in Italy, the loud "Pow" of a blowout. It was Mauro's rear tire. He was riding tubulars that were securely glued on. With nearly numb, wet fingers, he struggled to get the old tire off. Finally, with the repair complete, we realized that we were frozen to the core. I mean really, really cold. We rode through the traffic of Como, hoping to get warm. I saw a thermometer that read 5°(C). Every stop light chilled us. At last, out on the road next to Lake Como, heading north-north east to Bellagio we started to really roll. With each climb we would warm up and with each descent, the cold, wet air would rip the heat from our bodies. There was no point in stopping for pictures because the lake and the opposite shore were entirely obscured by the low-lying clouds. Stopping and getting even more chilled was unthinkable, anyway. I understand why Dante filled the lowest level of hell with ice.

At Bellagio, we turned south and headed for the barn. Just at the southern end of the lake, the massive, craggy cliffs of the opposite shore could be barely seen through the clouds. On a clear day they are spectacular. Then, through a pair of long, and comparatively warm tunnels and a quick trip through the north Milan traffic, we were back at Mondonico's. 125 kilometers (75 miles).

When we returned to Mondonico's from the hotel with the road grime washed off and sensation returned to our extremities, we found another nice surprise. Antonio and his son Giuseppe had cleaned and oiled our bikes. Shiny, none the worse for the wear (unlike the riders), they sparkled under the workshop lights. There is no hospitality like Italian hospitality, and the Mondonicos are the best of show. The luggage and bikes were loaded into the van with only a little trouble, and we were off to Volterra.

March 27, Saturday

People have been living in Volterra since before recorded time. It is an ancient walled city sitting about 1,800 feet above the valley floor. The Etruscans took it from the ancient Villanovans (iron-age people) that lived there, the Romans from them, Vandals from the Romans, Goths, etc.

We chose to stay at the Hotel San Lino in Volterra. These people were fantastic to us. In order to really enjoy sports, you must feel good, mentally and physically. That means all the little petty concerns and discomforts that can disturb you must be fixed or put aside. These people did it. We wanted breakfast served earlier and the desk clerk phoned four different employees to find someone who could come in early and slop the hogs (anyone watching hungry cyclists eat would probably think this phrase does a disservice to pigdom).

We chose to stay at the Hotel San Lino in Volterra. These people were fantastic to us. In order to really enjoy sports, you must feel good, mentally and physically. That means all the little petty concerns and discomforts that can disturb you must be fixed or put aside. These people did it. We wanted breakfast served earlier and the desk clerk phoned four different employees to find someone who could come in early and slop the hogs (anyone watching hungry cyclists eat would probably think this phrase does a disservice to pigdom).

Tires pumped, riders stuffed, pockets packed, bottles filled and we were off. We were very concerned about the weather after the previous day. No rain. It appeared cool and breezy. Not perfect, but improved. We rolled out and started the descent down the long series of switchbacks to the valley floor. The zephyr turned into real wind, strong enough that we had to go slowly and carefully because our bikes were getting blown around. Once on the valley floor, we were fine. We planned to ride from Volterra (in Tuscany, southwest from Florence), head east and north to San Gimignano, then north to Certaldo, then southeast to Vicarello, Spadoletto, south to Saline di Volterra and then up the 9 kilometer climb to Volterra. It looked like a good morning's work.

The roads were empty. We had Tuscany to ourselves. The hills were green, but the clouds were thick and dark. Like last year, we had packed 39-53 front rings with 13-23 rear nine speed cogs. As we rode to San Gimignano, the hills were steep enough to need the 21, but there was no real call for the 23.  From a distance, the distinct and unusual profile of San Gimignano stands out. At one time, there were 60 or 70 towers piercing the sky inside the walls of this little hill town. Now there are only 14. From miles away, you can spot the little town up on the hill. As we came to the city walls, the hordes of tourists and tour buses seemed to overwhelm the little ancient city. We saluted the city, regretted the press of tourists and rolled on, turning west just outside Certaldo.

From a distance, the distinct and unusual profile of San Gimignano stands out. At one time, there were 60 or 70 towers piercing the sky inside the walls of this little hill town. Now there are only 14. From miles away, you can spot the little town up on the hill. As we came to the city walls, the hordes of tourists and tour buses seemed to overwhelm the little ancient city. We saluted the city, regretted the press of tourists and rolled on, turning west just outside Certaldo.

The wind came up. This time, with a vengeance. We grabbed our bars firmly to steady our bikes and pressed on. Just after Vicarello, there is a fork that is a short 10 kilometer trip back to Volterra. At that point, the winds seemed to have moderated, so we continued our big loop, getting a tailwind for a few kilometers. At Saline di Volterra, the winds grew stronger than any I remember. I have never, ever ridden in wind this strong. We were OK except for an occasional unsheltered part of the road. Since we were in very hilly country, there was a little side shelter on either the right or the left of the road because the roads were cut into the hillside. Occasionally there would be no shelter, and the winds could roar right across the road. At one point as I was riding up to Volterra, a moped rider got off his bike, afraid that I might be blown into the oncoming lane and hit him in a gust of wind. I even had to walk my bike across a short unsheltered gap after almost falling over at about 5 miles an hour. At last, we triumphed. We rode only 57 miles, but it took us over four hours.

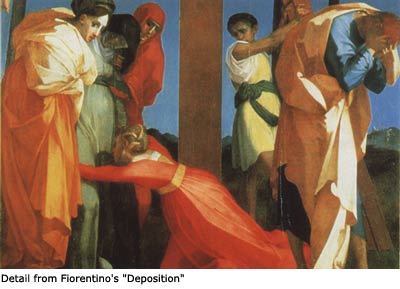

That afternoon, we started to explore the city. Volterra is not packed with art like some cities, but there are some real finds for the lover of fine art. The famous art museums of Italy are magnificent, but sometimes it's nice to take works of genius in small bites. You can digest them, think about them, and turn them over in your mind and remember them. In this little town is one of my favorites, Rosso Fiorentino's "Deposition". Its unusual colors and superb composition stop anyone walking by it. I believe that it is the most perfect depiction of grief in modern painting. Also sitting in Volterra's little gallery is a superb Ghirlandaio (teacher of Michelangelo), a Luca Signorelli, and a Daniele de Volterra (student of Michelangelo). Enough eye candy for the greedy art lover. Volterra also has some fine preserved Roman ruins, with an amphitheater and baths. They are fenced off for now.

|

|||

|

|||

March 28, Sunday

The sky was completely overcast, with some heavy looking clouds, but it was not raining. The Hotel San Lino again started breakfast early for us. This time, we planned to head due south. I've wanted to ride the road from Volterra to Massa Marittima for some time. Today was the day to do it. Celestino Vercelli of Vittoria Shoes had warned us that this was an uncompromising road, with lots of serious climbing. We were ready. The long ride down the hill from Volterra to the valley floor had to be done with some care, as the roads were still wet from the evening's rain. Then we started to climb. The first climb, with switch backs ("tornanti" in Italian) lasted almost an hour. From then on, the rising and falling road was relentless. At one point, there was a flat 100 meters, and it was a strange enough experience the Mauro had to remark it. We descended into Lardarello, with its massive geothermal works. Huge pipes that go on for miles rise out of the ground carrying the heat of the earth to the power plant. Then more climbing into Castelnouvo.

In Italy, it is not unusual for the main road between cities to go through little towns, mercilessly funneling the traffic through little streets hundreds of years old that were never meant for more than an ox cart. It can make for challenging and interesting riding. On we rode until a little after 10:30. We wanted to be back in time for lunch, and felt that a little less than five hours was enough exercise for the day.

As we were nearing the top of a long climb, I grabbed a Clif bar. Once my mouth was stuffed, Mauro attacked. I had to finish my bar because my legs were just getting the "knock". It was hard to eat, watching him speed up the hill.

I gulped down my food, jammed it into the big ring and went after him. Too late. We had crested the hill. Mauro descends like a fiend. I gave I it all I could, but he pulled away some more. There is no way I can catch him on his home turf as he skirted through the little cities, weaving and bobbing through the cars. Up and down the hills we rode until we came to a long, hard climb. Got 'im. I really wish he would have had the decency to look tired after all that.

While I mention traffic, once out of each little, tiny town, there was almost none. This beautiful road is one of the finest cycling routes I have ever ridden. It compares with the road in Mount Subasio Park leading in to Assisi, with the advantage of being longer.

By the time we were headed back, we had wind breakers and arm warmers off. A perfect day, in the low 60's. Cool enough take the heat out of the climbs, yet not cool enough to chill. We arrived after a bit more than four hours, having ridden about 70 miles. This was good.

Monday, March 29

Last year, we all found that eight straight days of four to seven hour hard rides pushed us to the limit. This year, we decided to put in a rest day so that we could ride with less fatigue and more pleasure. We left our luggage and bikes at the San Lino and took a day trip to Florence.

Since my first visit to Florence in the early 80's, I have been frustrated in my attempts to see the Masaccio frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria della Carmine. The long restoration and scheduling miscues have prevented my seeing one of the seminal works of western art. The restoration was finished, and it did not appear that the chapel would be closed. I love this country, but sometimes figuring out when an Italian monument will be open or closed involves differential calculus, string theory, and numerology.

We got there just at opening, bought our tickets and waited for our turn. The chapel allows only 35 people in at a time, allowing a nice, uncrowded chance to appreciate Masaccio's accomplishment.  I hate to think of what the lines in the summer must be. The restoration and cleaning of the frescoes were themselves a work of art. The colors were bright and shone as if painted yesterday.

I hate to think of what the lines in the summer must be. The restoration and cleaning of the frescoes were themselves a work of art. The colors were bright and shone as if painted yesterday.

A quick note about these frescoes. Brancacci, in the early 1400's, commissioned Masolino to paint a cycle of frescoes in a chapel in Santa Maria della Carmine, a church across the Arno from the Florence city center. Masolino brought with him Masaccio (Masaccio means "Big Tom".) After laying out the plan and doing some very, very ordinary painting, Masolino left town for other work. He told Masaccio to just keep painting. Masaccio the apprentice did what he was told. By himself, in only his mid twenties, he proceeded to do some of the finest painting of all time. This is early renaissance work, yet the perspective is dead on, the three dimensionality, the modeling, everything, is masterful and way ahead of its time. Years later, even Michelangelo and da Vinci came to study and learn from them. This was a work of glorious genius, and I finally got to see it. Masaccio, by the way, headed of to Rome at about age 27 and vanished from history. What would he have done if he had been given Titian's 99 years?

The rest of the day was a cruel, cruel, disappointment. Rome and Florence (I don't know about the other great Italian art cities) are preparing for the Jubilee in the year 2000. Massive restoration works are going on, as the following paragraphs explain.

We walked over the 13th century bridge, the Ponte Vecchio, on our way the Cathedral and Baptistery. Our first goal was to visit Benvenuto Cellini's "Perseus". Both Terry and I had read the moving story of the casting of this bronze in Cellini's Autobiography (This is one of the great books. If you want to get the feel of Renaissance Italy with all of its glories and hideous warts, this is the book). I walked directly to where it was supposed to be in a loggia in the city square. Gone for restoration. Then I set out to revisit the Ghiberti "Doors to Paradise". Copies. The real doors were in the Cathedral museum. Fair enough. We'll go there later. We went into the cathedral to see Florence's own Michelangelo Pieta. Gone to the museum.

Well, off to the museum. Closed for restoration for the Jubilee.

Santa Maria Novella. Closed for restoration.

Laurentian Library (with stairs designed by Michelangelo). Closed for Restoration.

Church of San Lorenzo. Closed.

Uffizi Art Gallery. Closed on Monday.

Medici Chapels. Closed on Monday.

Those few items that were open were overwhelmed with tourists looking for a few tidbits. The line to view the mosaics on the ceiling of the baptistery stretched forever, as did the line to go up into the Cathedral dome. Foot sore and a bit disappointed, even with our Masaccio triumph, we headed back to Volterra to get our bikes and luggage and head for Orvieto. From what I have learned, I would recommend that anyone planning on seeing Rome or Florence put it off until next year. Too many of the real blockbuster sights are unavailable. I have no idea what effect the Jubilee will have on crowds, but I might suggest even waiting until 2001. No matter what, do a lot of research and ask a lot of hard questions. Remember, most sources of travel information want to sell you travel. No one is publicizing this short-term fiasco because no one will make any money being honest about it. The whole travel industry is keeping it quiet. Caveat Emptor.

Arriving in the early evening at Orvieto's Hotel Duomo, we were greeted by Signora Maura and her daughter. We were immediately enveloped with caring, maternal hospitality. As we unloaded the luggage, it was whisked off to our rooms. We had made previous arrangements for big breakfasts. Signora Maura asked what, exactly, we needed to eat, and when we needed it. She made sure that there was a safe place for our bikes. Mauro Mondonico's mother, Gabriella, is a very loving, sweet woman who worries about Mauro ("Wear an extra jersey, it's cold out"). I told Mauro that Gabriella could relax, because we were in the hands of a kind, competent Italian Mama. Call it a lateral hand-off.

After unloading the van, we ran into a common problem with little medieval cities overwhelmed by cars. Parking is extremely difficult. We headed down to the parking lot and incorrectly thought that it only allowed day parking. We drove back up to Signora Maura for more help. She told us we could park in the evening without problem, but that she had a friend who could rent a space to us for the time we were there. She grabbed a key, put on her coat and went down a narrow alley to a giant locked steel gate set in an ancient wall. You never know what you will find behind big, old, weather-worn Italian walls. Sometimes the most distressed exterior will yield the most exquisite and luxurious interior.

Not so this time. She unlocked the gate and swung the doors wide open. Inside was a lot, the first half was filled with parking spaces covered with a jerry-built roof made of various pieces of junk. Farther back, the lot was littered with all kinds of junk and debris, flowing into all sorts of irregular corners in the lot. Way in the back was another couple of old covered structures made of I-don't-know-what. And sitting back in one of these buildings (?) was an old man. It appeared that he was the owner of the spaces. It looked like he just spent all day behind this locked gate sitting in the chair amidst all his junk. I guess it beats driving the 405 for a couple of hours each day to get to work, but it was a strange place.

As I have noted in other stories, Mauro is the best driver I know, by a long shot. The promoters of pro races hire him to drive the UCI Commisar in such important races as the Milan-San Remo and the Tirreno-Adriatico. Mauro looked at the narrow alley and the tight turn in to the lot and pronounced it impossible. "There is no way I can get the van around the corner." Now, had sense prevailed, that would have been the end of it. Sense did not prevail. The old man assured him that it would work, so we all took up stations at either end of the van, Signora Maura, the old man, and I. As he wiggled, squirmed, and turned the van this way and that, trying to edge it into the lot we shouted instructions and waved our hands at him just like in an Italian comedy. Clearly frustrated (and maybe a bit angry), he kept his cool until we all realized that the van was almost completely stuck, and there was a line of people wishing to drive up the alley (merely because a road is a narrow alley does not preclude it from being an important and well used passageway in Italy). Some help we three geniuses were.The long process of getting the van unstuck was started with the stopped motorists patiently waiting for the road to clear. Unstuck, and covered with only a little sweat, Mauro and I found that most precious of all items in hill-top towns: a free parking space.

March 30, Tuesday

Orvieto sits atop a promontory of volcanic rock, rising up from the hilly Umbrian countryside. Its highly defensible position has made it an inhabited spot since pre-history.  It is famous for its cathedral that was built to celebrate the "Miracle of Bolsena", in which the host during mass bled upon a doubting priest. While this cathedral is magnificent and striking, the real appeal of Orvieto to a romantic like me is its little winding streets with buildings made of the same dark volcanic rock the city sits on. It's a pleasing, worn, but well-scrubbed city that grows on the visitor. Architecture aside, the lure to a cyclist to come to Orvieto is the hilly Umbrian countryside. As I write this, I can think of few finer places to ride a bike. Challenging and beautiful, this is a land that must have been made for cyclists (that have a 39-23 or lower). For our first day in Umbria, we wanted a long, challenging ride. We got it, in spades. We planned a huge circumnavigation of Lake Bolsena, riding in the surrounding hills through Castel Giorgio, Valentano, Tuscania. We then planned to ride north to the lake (about 12 kilometers) to Montefiascone, along the lake to Bolsena, and then home.

It is famous for its cathedral that was built to celebrate the "Miracle of Bolsena", in which the host during mass bled upon a doubting priest. While this cathedral is magnificent and striking, the real appeal of Orvieto to a romantic like me is its little winding streets with buildings made of the same dark volcanic rock the city sits on. It's a pleasing, worn, but well-scrubbed city that grows on the visitor. Architecture aside, the lure to a cyclist to come to Orvieto is the hilly Umbrian countryside. As I write this, I can think of few finer places to ride a bike. Challenging and beautiful, this is a land that must have been made for cyclists (that have a 39-23 or lower). For our first day in Umbria, we wanted a long, challenging ride. We got it, in spades. We planned a huge circumnavigation of Lake Bolsena, riding in the surrounding hills through Castel Giorgio, Valentano, Tuscania. We then planned to ride north to the lake (about 12 kilometers) to Montefiascone, along the lake to Bolsena, and then home.

The first part was flawless and stunning. The countryside was beautiful as always, and there were very few cars. We rose and fell, using our 23's a lot. I didn't remember the climbs being this stiff last year. I think this area was tougher, even if I am another year older.

At Tuscania, the southernmost point of the trip, we headed east, into a ferocious headwind. Mauro will take cold, wet, chill-you-to-the-bone rain, but he hates the wind. I, on the other hand, am philosophical about wind, and am willing to just gear down. That all would have been fine, but we could not find the planned road north, so we had to go all the way to Viterbo. As we got closer to the big city, the dense traffic with heavy trucks stretched my philosophical resolve.

Reaching Viterbo and on our way to Bolsena, we were back in classic Umbria. As we rode, we could see Montefiascone rising up in the distance, rising way, way up. At first, it looked like the road was going to pass between the two hills and go around Montefiascone. Foolish boy! Roads are to connect cities, and old Italian cities are on the tops of hills. This was a climb. Our legs were soft. We had to use our 23's out of the saddle. We passed by a cemetery. Should we just stop here and die? Onward to the top. And then, a view of Lake Bolsena. Beautiful. The visual rewards just keep coming. The descent took several kilometers with the road rising and falling a bit as we rode along the edge of the lake. At Bolsena, we had to do a tough climb over the Volsini Mountains then along the ridge line for ten kilometers, and then a descent to the valley floor.

Then, the dark side to staying in a beautiful Italian hill town, the climb up to to the hotel. If we want to eat, we have to climb. Any strength left in our legs was drained, or at least so I thought. Mauro dropped a cog. Damn. He dug down deep to find power from somewhere and we flew up the hill. I gritted my teeth and gave it everything I had until, a couple hundred yards from the city gate, I cracked. I limped in. Mauro was there at the hotel entrance having a drink from his bottle, looking indecently and rudely fresh. Would a jury of cyclists convict my of what I wanted to do if I had the strength? Total distance, 140 kilometers in five and a half hours. A good morning's work if we ever walk again.

Then, the dark side to staying in a beautiful Italian hill town, the climb up to to the hotel. If we want to eat, we have to climb. Any strength left in our legs was drained, or at least so I thought. Mauro dropped a cog. Damn. He dug down deep to find power from somewhere and we flew up the hill. I gritted my teeth and gave it everything I had until, a couple hundred yards from the city gate, I cracked. I limped in. Mauro was there at the hotel entrance having a drink from his bottle, looking indecently and rudely fresh. Would a jury of cyclists convict my of what I wanted to do if I had the strength? Total distance, 140 kilometers in five and a half hours. A good morning's work if we ever walk again.

After a late, but huge lunch, we set off for one of the reasons we selected Orvieto. This small, classic Italian hill town has an absolutely spectacular cathedral. The facade is a complex white marble front with sculptures, bas-reliefs, and mosaics. Sitting in the little city square, the facade of the cathedral is the most striking and eye-catching I have seen in Italy. This does not mean that it is a well-designed, ordered, work of art. To my eye, it is more of a giant knick-knack shelf that the people of Umbria have been adding to for generations. For any artistic failings it has, it does grab you and make you stare.

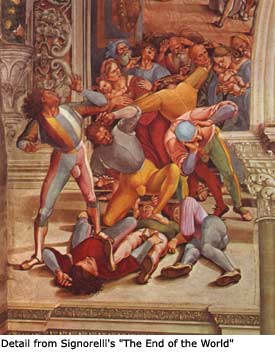

Inside the cathedral was the object of our pilgrimage, the "Apocalypse" frescoes by Luca Signorelli. I saw them 15 years ago, but I wanted to revisit them, with a few extra years and I hope, some more learning and understanding, under my belt.

The frescoes were finer than I remembered. In a chapel in the side of the cathedral, Signorelli took over the unfinished job of portraying the end of the world that Fra Angelico started in the mid 1400's. What a difference a half century makes. When Signorelli took over from Fra Angelico, the science and art of painting had leaped into the full renaissance. Signorelli boldly portrayed the human body with exacting precision. None of Leonardo's beautiful wooded backgrounds, no extra architecture. Just the human body, going off to heaven, being sent to hell, confronting the end of the world, being resurrected, all done in an almost Attic-like worship of the human form. Art critics complain that it is all bodies with no depth of feeling; Michelangelo without his emotional power. Maybe there is some truth to this, and people whose opinion I respect believe it, but this is powerful, powerful stuff, rarely bettered on this little planet. I just hope he's wrong about how it will end for us sinners.

The frescoes were finer than I remembered. In a chapel in the side of the cathedral, Signorelli took over the unfinished job of portraying the end of the world that Fra Angelico started in the mid 1400's. What a difference a half century makes. When Signorelli took over from Fra Angelico, the science and art of painting had leaped into the full renaissance. Signorelli boldly portrayed the human body with exacting precision. None of Leonardo's beautiful wooded backgrounds, no extra architecture. Just the human body, going off to heaven, being sent to hell, confronting the end of the world, being resurrected, all done in an almost Attic-like worship of the human form. Art critics complain that it is all bodies with no depth of feeling; Michelangelo without his emotional power. Maybe there is some truth to this, and people whose opinion I respect believe it, but this is powerful, powerful stuff, rarely bettered on this little planet. I just hope he's wrong about how it will end for us sinners.

After leaving the cathedral we decided to wander in and out of the little, narrow, ancient streets. We ended up on one of the edges of town and saw an old church.  Carol and I walked in. What followed was one of those beautiful, wonderful hours that the traveler gets to have if he is really lucky. The little church was San Giovenale. It was half dark inside. We could see old, thick round columns, some repaired with bands of iron around them, reaching up to low, thick, round arches. This was pre-gothic (Lombard?). The frescoes were old and half gone, but the sense of the fantastic age of the church was overpowering. At the front of the church was an old man at a little desk. He didn't speak English, but he kept his Italian simple enough for us to understand. He was Toni, a retired musician who had staked out this little, partially ruined church as his cause. San Giovanale was started just after 1,000 A.D.

Carol and I walked in. What followed was one of those beautiful, wonderful hours that the traveler gets to have if he is really lucky. The little church was San Giovenale. It was half dark inside. We could see old, thick round columns, some repaired with bands of iron around them, reaching up to low, thick, round arches. This was pre-gothic (Lombard?). The frescoes were old and half gone, but the sense of the fantastic age of the church was overpowering. At the front of the church was an old man at a little desk. He didn't speak English, but he kept his Italian simple enough for us to understand. He was Toni, a retired musician who had staked out this little, partially ruined church as his cause. San Giovanale was started just after 1,000 A.D.

He gave us a lecture on the history of the church, showing us which frescoes were from the schools of Cimabue, Duccio, Giotto, etc. The church has an addition with a barely pointed set of arches at the crossing, showing just the earliest hint of the beginning of the Gothic advances in building technology.  Toni showed us the priceless Byzantine altar with the name of its ancient sculptor carved in its side. In his love for his old church, Toni quietly, but bitterly complained that this little dull church with all of its history got almost no money for restoration. All the money went for big, spectacular projects. There was almost nothing left for these little, precious pieces of our past. Toni, here's hoping the world loosens its purse for you.

Toni showed us the priceless Byzantine altar with the name of its ancient sculptor carved in its side. In his love for his old church, Toni quietly, but bitterly complained that this little dull church with all of its history got almost no money for restoration. All the money went for big, spectacular projects. There was almost nothing left for these little, precious pieces of our past. Toni, here's hoping the world loosens its purse for you.

We were in Umbria, and that means riding, and riding in the hills. We selected a challenging loop, leaving Orvieto and heading northwest to Todi and north up to Callazone and then west to Marsciano and south to Orvieto. Mauro made sure that if we were going to go to Todi, there would be no consideration or thought of going up the climb to the city. It was just too hard, he had done it last year, and besides, he could not risk another disqualification (click here for an explanation). We were set in our route with a nice long, beautiful loop. At least that was the plan. We climbed steadily for an hour and a half. These weren't little 53-19 or even 39-18 hills. We were working the 21's and 23's in the little ring. It was slow going, but worth it. The road was lonely and we were in a countryside just coming alive with Spring. The sun was out, and the smell of the flowers and herbs growing along the roadside let us know that the yearly renewal of life had begun. The grapevines were just beginning to bud.

Outside Todi, the climbs got harder. By San Terenziano, we had been out for three hours and were only about a third done. If we finished the ride as planned, we would be out of time and out of legs before we were out of road. As we rode out of the saddle in 39-23's, giving it all we had, a farmer called out that we were almost to the top. Mauro and I strained a bit harder to finish off the climb. A cruel joke. As we rounded a corner, an everlasting wall of road confronted us. Yet, as we looked out into the valleys below, we felt we were well repaid for our work. The patchwork farms stretching off into the distance look just like the paintings of the same lands done by Lorenzetti hundreds of years ago.

At the road to Pantalla, we turned off the planned road and headed west and south. At Todi, we crossed the road that brought us in and jumped on the main road back to Orvieto, the 448. Lucky boys!  This road follows the Tiber river as it swells and wanders through Umbria. Some places it has carved out Swiss-like lakes and gorges. Several times, we had to stop and just take it all in. In no time at all, there was Orvieto. And yes, once again Mauro flew up the hill with five really hard hours of riding under his belt. Where did he get this energy?

This road follows the Tiber river as it swells and wanders through Umbria. Some places it has carved out Swiss-like lakes and gorges. Several times, we had to stop and just take it all in. In no time at all, there was Orvieto. And yes, once again Mauro flew up the hill with five really hard hours of riding under his belt. Where did he get this energy?

Later that afternoon I went out for a lemon gelato. Italians demand that their food be made of fresh, natural ingredients. One of the consequences of this is that lemon gelato is made with those yellow, round things that actually grow on trees. The hearty, delicious taste of real food characterizes all Italian cuisine, even something as simple as a lemon gelato. The comparison shows our chemical, highly processed American food to be the junk that it is.

When I got back to the hotel, Mauro was covered with greasy grime. He had taken it upon himself to do a little maintenance on the bikes and lube the chains after all the wet riding earlier in the week. Thanks.

April 1, Thursday

Mauro proclaimed that there would be no hills today. He failed to reckon with where he was. If you are going to go anywhere around here you are going to move in all three dimensions. Vertical travel is obligatory if one is to accomplish horizontal movement. A shorter day was planned. We were tired and needed a bit of a rest, and we had a long drive to Urbino ahead of us. We headed west to Aquapendente and then south to the north Shore of Lake Bolsena. A beautiful spring day. Italians take it as an article of faith that Spring comes in the last week of March. They are so right. I wish it had come a couple of days earlier, but out on the lonely roads, the only sound is of the birds, the tires on the road and the wind whistling in our ears.

We came back to Bolsena as we did two days ago, but with the intention of coming back to Orvieto through another road. Bolsena was warm and beautiful, so I called for a halt in the city center for a cappuccino and a brioche. We parked our bikes outside and walked into the bar. Now a bar in Italy is not like a bar or pub in the U.S. where beer and cheap Irish whiskey is swilled. It is more of a coffee house, or lunch spot that will serve alcohol upon request. The locals usually gather at their favorite bar to play dominoes, argue politics, and sometimes watch soccer (Italians call soccer "calcio") on TV.

We pulled out our maps to ask the owner for final directions. Everyone in the bar gathered around and wanted to know where we had been, how long we had been out, and even where we had been riding in days prior. We were in Italy, and we were doing "sport". Everyone was our friend. We had our snack and amid a hail of "Ciao, Signori" we were off to Orvieto for the last time.

As we climbed up the switchback out of Bolsena, a nice lady that we had met at the bar (honest Mom, it really doesn't mean the same thing as in the U.S.), slowed her car and waved to us.  As we rode along the top of the hill, we met a moving an impassable obstuction. Shepherds were moving their flock. There was nothing to do but wait. Who cares, it's a fine day, the sun was out and the birds were singing.

As we rode along the top of the hill, we met a moving an impassable obstuction. Shepherds were moving their flock. There was nothing to do but wait. Who cares, it's a fine day, the sun was out and the birds were singing.

This time, we made the final climb together. I think he's weakening.

We had been taking lunch in the restaurants of Orvieto. Mauro agreed that they are the slowest restaurants we have ever eaten in. I'm generally in no rush on these trips, gastronomy being one of the reasons for coming here. The food had been superb, but they really do take their time here. We packed up our bikes and luggage and had lunch at one of the chain restaurants along the Autostrada (toll highway). The food there is always good, if not of gourmet quality. Italians will not put up with bad food. If you are traveling in Italy, don't be afraid of stopping to eat along the road at one of these places. If you are short of time, you'll save an hour and be quite pleased.

The road to Urbino is over more craggy Apennines. Mauro once again showed that he was the best driver I have ever seen. He cornered, braked, and accelerated with an ease that I can only envy. We arrived at the Hotel Mamiani in short time, just outside the city walls of Urbino.

When I book a hotel for these trips, I am exacting. I try to think of everything that we cyclists need in order to accomplish our goal: a pleasant, untroubled stay with good riding. Usually, when I request big breakfasts, late checkout, etc. the faxed response from the hotel generally answers only some of my questions. Difficult questions, or those that might generate a negative answer, are often ignored, requiring me to re-fax and get precise answers. Theresa, the concierge at the Hotel Mamiani gave precise, perfect, and complete answers to my questions. Everything we wanted was granted to us, and with enthusiasm. I was so taken by the extraordinary efforts Theresa went to to make sure we were happy, I faxed the correspondence to my father so that he could see how well I was being treated (and this was just in booking the room). This was real service!

I walked into the hotel lobby and announced myself and my friends, "Siamo ciclisti coraggiosi" (we are the brave cyclists). We got an effusive welcome. The manager of the hotel came out to meet us. They had a special locked room for our bikes. The bags were taken to our rooms, which had fresh fruit waiting for us. Excellent. Another bonus: the beds were firm and comfortable, absolutely first-rate.

Friday, April 2

Since we were the courageous cyclists, we planned a truly serious ride. We planned to ride to San Marino, around to San Leo, to Marcerata, Sassocovaro and back. First, breakfast. The Mamiani's breakfast buffet that greeted us was a cyclists dream. Fruit, breads, cakes, cheeses, pots of coffee, jams, cereals. I think we all ate to threshold of pain, both because the food was so good, and we knew we would need every available calorie.

After demolishing the buffet (don't worry, there were no women and children watching) we changed into our cycling clothes. As I clicked awkwardly into the lobby, Theresa the concierge burst out laughing. "You look ridiculous!"

Off the bike, cyclists do look odd. Her joshing, by the way, was perfectly good-natured, we were among friends. Anyway, she was right. Well, maybe only a little ridiculous.

We mounted our bikes and headed off into the mountains. Just when you think Italy has shown you her best, that there can be nothing finer or more beautiful that the last amazing sight, she opens up and amazes you with still more and greater beauty. My father taught me that you cannot superlative a superlative. He hasn't ridden in the hills of Marche. This was good, hard riding. The climbs were steady and long with the valleys stretching out below us, the hills rolling off into the distance. The beauty of the land below, the lonely roads, and the feel of a bicycle that is a work of art made my joy complete.

I was reminded of the lines from Izaak Walton's, "The Compleat Angler".

- "I was for that time lifted above the earth,

- And posses'd joys not promised in my birth."

We could see the unique craggy profile of San Marino in the distance. San Marino, like the Vatican City, is a wholly sovereign and independent country inside Italy. As a little boy, I collected their postage stamps. They were always the most beautiful, coming in strange sizes and shapes. I always wanted to go there, thinking it to be a special and exotic land. When I finally got there, a few years ago, I found tourist shops selling the usual tourist kitsch and liquor and cigarettes with low San Marino taxes. Another bubble burst. As you cross the San Marino boundary, a sign announces that it is the ancient land of liberty. They should add, also the land of cheap tobacco and whiskey.

From San Marino, we headed off to San Leo. That was a long, hard climb. 23's almost all the way. As we turned one corner, we met a group of German cyclists with a follow van. They were nice guys, down in Italy for Easter. Part way up they climb they stopped to regroup and we climbed on.

The sign said, San Leo: four kilometers. Then, San Leo: three kilometers. I thought kilometers were short. I think in these hills, kilometers are several miles long. At last, we reached the top, with the city of San Leo glued onto the side of a giant rock.

The sign said, San Leo: four kilometers. Then, San Leo: three kilometers. I thought kilometers were short. I think in these hills, kilometers are several miles long. At last, we reached the top, with the city of San Leo glued onto the side of a giant rock.

Down the hill. We descended at a moderate rate, knowing that there was a lot more climbing to do. As we rolled into Montecopiolo, "Messerschmidts at 10 o'clock!" The nice, sweet, gentle German cyclists we met and dropped on the climb were coming down the mountain like crazed bees, weaving and swarming in and out of traffic, absolutely fearless. We joined them until we hit the flats on the valley floor. Then, instead of pressing on at the same insane speed, they dropped down to about 15 miles an hour. We left them and rode on. We discovered in the insanity of the crazed descent, we missed our turn. That meant that we had much more climbing to do than planned. Well, we were here for the ride and this was truly the best riding of my life.

We arrived at the Mamiani after six hours. We walked (slowly) into the hotel, our bikes were taken from us and whisked away. How nice. The hotel staff asked if we enjoyed our ride. "The most difficult, most beautiful, and most rewarding ride of my life", I answered.

After being autoclaved and fed, it was time to go to town. Urbino has a special history. The Dukes of Montefeltro ruled the area from the 1100's. They grew rich and powerful. In the middle 1400's, Duke Federico increased the family wealth and power to its highest level. But the interesting time came when his son, Guidobaldo and his wife, Elisabetta of the Gonzaga family, ruled the city. This was the true Camelot. For perhaps twenty short years, the court of Urbino was the most refined, elegant, and civilized place on the earth. The Papal court of Rome might have been more brilliant, being able to draw on greater writers and artists with it greater wealth, but Urbino was more elevated and civilized. Men like Bembo and Castiglione, scholars and thinkers, gathered here.

After being autoclaved and fed, it was time to go to town. Urbino has a special history. The Dukes of Montefeltro ruled the area from the 1100's. They grew rich and powerful. In the middle 1400's, Duke Federico increased the family wealth and power to its highest level. But the interesting time came when his son, Guidobaldo and his wife, Elisabetta of the Gonzaga family, ruled the city. This was the true Camelot. For perhaps twenty short years, the court of Urbino was the most refined, elegant, and civilized place on the earth. The Papal court of Rome might have been more brilliant, being able to draw on greater writers and artists with it greater wealth, but Urbino was more elevated and civilized. Men like Bembo and Castiglione, scholars and thinkers, gathered here.

If the reader would like to get a sense of what life was like and how powerful, rich people thought, and spent time, Baldissare Castiglione's "The Courtier" is available in a Penguin paperback. It's brilliant, beautiful and elegant. If the reader seeks this fine book out, remember, our values are not the values of the 15th century. As someone once said, a man's virtues are his own, the defects are of his times.

Another digression: There is some agreement among critics and esthetes that two of the finest portraits are Rafael's portrait of Julius the Second (the Agony and the Ecstasy pope) and Titian's portrait of Innocent the Third with his two scummy nephews. I would like to submit that Rafael's portrait of Castiglione in the Louvre rivals them. Rafael doesn't try to capture power or domination or weighty cares. It is a penetrating picture of a sensitive, gentle, intelligent man. By the way, Cezanne loved this picture. It was also admired by Matisse. Rembrandt sketched a copy of it. I'm in good company.

The huge palace of the Dukes of Urbino that was the scene of such brilliant gatherings fell into terrible disrepair after Urbino became part of the Papal States. The church took the magnificent Montefeltro library and the best art off to the Vatican. What we see now is a shadow of its former magnificence. Yet the palace of a wealthy, powerful family with taste, it surely was.

The last day. As always, visits to Italy end all too soon. Mauro was feeling worn, so he decided to take the day off. Terry and I took off for the hills, heading down to Urbania then to Carpegna, east to Macerata and down the river valley back to Urbino. Climbing (yes, always climbing) out of Urbania to Peglio a local rider caught up with us, rode with us for a moment and then accelerated up the hill. We had to respond and defend our national honor. Terry was wearing his Northern California Champion's jersey, so he was under a doubly powerful obligation to get to the top before our Italian friend. We smoked up the hill. And then, in the complex streets of the little town, Terry and I became separated. He took the wrong turn and disappeared down a hill. I couldn't find him, but we both had maps. He went his own way and I kept to the original plan.

As I rode over the hills, the old men and women were getting their gardens ready. Italian mamas pushing wheelbarrows down the road to their garden plots and old, sturdy grandfathers hoeing the Italian earth were a common sight. Their ancestors had probably worked these same plots for untold centuries. As I rode along, people would wave to me. "Salve", we would say to each other. I really didn't want to go home.

About 20 kilometers from Urbino, as I was riding with all the intensity and drive of Ferdinand the Bull smelling the flowers, a couple of Italian racers caught me. At the speed I was going, the Italian mamas with their wheelbarrows couldn't catch me, but I wouldn't open up much of a gap. The racers looked magnificent in their red and black tights, jerseys, and gloves. I jumped on their wheels and we really cooked. Between gasps I found that they were headed to Urbino, so here was a fine finish to the ride.

The final climb to Urbino isn't a stiff climb like Orvieto or Volterra, but a small ring seemed appropriate to me. Not to these guys. We stormed up the hill, pretzeling our bikes to keep the big gears going. My legs started to really scream as I tried to hang on, trying to ignore yesterday's six hours in the hills. The stronger rider dropped a cog and accelerated. Too much for me. "Ciao, Raggazzi!" (See you, boys) I gasped. They waved goodbye and disappeared up the hill.

At that point, I was just about at the hotel. I turned off and rode to the parking lot. There, taking in the beautiful Montefeltro hills were Mauro and Terry, waiting for me to return. The beautiful riding was over. We packed our bikes and drove back to Concorezzo and the long flight home.

A few notes.

I wanted to test the new Vittoria "Raider" shoe. I had been riding them for a short while at home, but riding day after day for four to six hours at a time with long climbs is the ideal way to test a product. This is how to find a product's slight tendency to cause discomfort or break, or any other shortcoming it might have. The "Raider" is an updated version of the "Blitz" that Pantani used in his Giro-Tour double win. The superior upper closure and reinforced ankle area took an already superb shoe and made it just a little bit better. The three closures allow the rider to both cinch the shoe to the exact shape of his foot, and to optimally loosen and tighten various parts of the shoe as comfort demands. My feet were far, far happier than my weary legs.

The Hotel Mamiani in Urbino, with its informal, yet caring service was the best hotel I have ever visited. When Mauro and I were washing up after packing the bikes for the flight home, I asked him if he wanted to do this again next year. "Yes, but only if we stay at the Mamiani." The Hotel Duomo in Orvieto must be given credit for its own fine brand of family owned, small hotel service. I'd go back there in a heartbeat.

I had never ridden in the district of Marche (in English, The Marches) on the east coast of Italy. Up until now, I thought Umbria was the ultimate cyclist's paradise. Marche equals the best Umbria has. If you go there, bring your gears.

With the exception of the freak blowout in Como, we had no other flat tires. My own tires did not even have a cut. After the first day, Mauro rode the Torelli PGV's I gave him last year. They still do not even have a cut. The virtues of a culture that recycles and shows care for the resources of the earth can show up in unsuspected ways. There is almost no glass on the roads of Italy. If only they can get rid of that damn diesel smoke.

I'm barely back and am already poring over maps, planning the next trip. I'm like the boy who has opened all of his Christmas presents and by noon is already counting the days until the next Christmas. Arrivederci, Italia. See you again.