1953 Giro d'Italia

36th edition: May 12 - June 2

Results, stages with running GC, photos and history

1952 Giro | 1954 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1953 Giro Quick Facts | 1953 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1953 Giro d'Italia

David L. Stanley's masterful telling of his bout with skin cancer Melanoma: It Started with a Freckle is available in print, Kindle eBook and audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

4,035 km raced at an average speed of 34.02 km/hr

112 starters and 72 classified finishers.

Hugo Koblet took the lead in the stage eight individual time trial.

Everyone, including Fausto Coppi, seemed to think he would hold the lead to the end.

Convinced by his teammates that Koblet would be vulnerable on the Stelvio Pass in the penultimate stage, Coppi performed one of cycling history's great rides and won his fifth Giro, tying Alfredo Binda's record.

1953 Giro d'Italia Final General Classification:

I have two sources for team affiliations. One has the Spanish team sponsored by Ideor, the other says Fiorelli. I lean to Fiorelli because Fiorelli's regular pro team was managed by Mariano Canardo, director of the 1953 Spanish Giro team, and the Fiorelli team had several Spanish riders.

Fausto Coppi (Bianchi): 118hr 37min 26sec

Fausto Coppi (Bianchi): 118hr 37min 26sec- Hugo Koblet (Switzerland-Guerra) @ 1min 29sec

- Pasquale Fornara (Bottecchia) @ 6min 55sec

- Gino Bartali (Bartali) @ 14min 8sec

- Angelo Conterno (Fréjus) @ 20min 51sec

- Stan Ockers (Belgium-Girardengo) @ 24min 14sec

- Giovanni Roma (Bottecchia) @ 24min 35sec

- Guido De Santi (Benotto) @ 25min 6sec

- Fiorenzo Magni (Ganna) @ 25min 39sec

- Vincenzo Rossello (Ganna) @ 26min 21sec

- Pietro Giudici (Ganna) @ 29min 2sec

- Nino Defilippis (Legnano) @ 29min 26sec

- Wim Van Est (Holland) @ 29min 57sec

- Fritz Schaer (Switzerland-Guerra) @ 30min 32sec

- Giorgio Albani (Legnano) @ 31min 17sec

- Donato Zampini (Levriere) @ 31min 54sec

- Arrigo Padovan (Atala) @ 32min 23sec

- Elio Brasola (Torpado) @ 33min 29sec

- Danilo Barozzi (Atala) @ 35min 25sec

- Agostino Coletto (Fréjus) @ 36min 49sec

- Silvio Pedroni (Ganna) @ 36min 54sec

- Andrea Carrea (Bianchi) @ 42min 6sec

- Bruno Monti (Arbos) @ 42min 15sec

- Roger Pontet (France) @ 44min 25sec

- Primo Volpi (Arbos) @ 45min 16sec

- Serafino Biagioni (Bartali) @ 47min 17sec

- Ettore Milano (Bianchi) @ 50min 1sec

- Walter Serena (Welter) @ 51min 2sec

- Bernardo Ruiz (Spain-Fiorelli) @ 54min 17sec

- Raphaël Géminiani (France) @ 54min 28sec

- Oreste Conte (Bottecchia) @ 56min 53sec

- Marcello Pellegrini (Welter) @ 57min 17sec

- Tranquillo Scudellaro (Legnano) @ 58min 18sec

- Giulio Bresci (Bartali) @ 58min 37sec

- Stefano Gaggero (Bianchi) @ 1hr 2min 7sec

- Rinaldo Moresco (Arbos) @ 1hr 5min 29sec

- Franco Franchi (Bottecchia) @ 1hr 7min 24sec

- Michele Gismondi (Bianchi) @ 1hr 9min 28sec

- Vittorio Rossello (Fréjus) @ 1hr 13min 9sec

- Livio Isotti (Ganna) @ 1hr 15min 4sec

- Andres Trobat (Spain-Fiorelli) @ 1hr 19min 52sec

- Armando Barducci (Legnano) @ 1hr 20min 12sec

- Jesus Lorono (Spain-Fiorelli) @ 1hr 20min 44sec

- Rik Van Steenbergen (Belgium-Girardengo) @ 1hr 23min 48sec

- Aldo Zuliani (Bottecchia) @ 1hr 26min 6sec

- Giovanni Pettinati (Levriere) @ 1hr 29min 5sec

- Giuseppe Doni (Torpado) @ 1hr 29min 32sec

- Marcello Ciolli (Fréjus) @ 1hr 32min 25sec

- Luciano Frosini (Arbos) @ 1hr 34min 11sec

- Mario Ciabatti (Fréjus) @ 1hr 36min 57sec

- Thijs Roks (Holland) @ 1hr 38min 42sec

- Fiorenzo Crippa (Bianchi) @ 1hr 40min 6sec

- Mario Baroni (Ganna) @ 1hr 42min 26sec

- Antonio Medri (Bottecchia) @ 1hr 45min 48sec

- Remo Pianezzi (Switzerland-Guerra) @ 1hr 50min 13sec

- Virgilio Salimbeni (Ganna) @ 1hr 50min 50sec

- Miguel Gual (Spain-Fiorelli) @ 1hr 52min 15sec

- Luciano Maggini (Atala) @ 1hr 52min 25sec

- Dante Rivola (Bartali) @ 2hr 0min 39sec

- Aloïs Van Steenkiste (Belgium-Girardengo) @ 2hr 17min 33sec

- Nino Assirelli (Arbos) @ 2hr 19min 20sec

- Mario Gestri (Arbos) @ 2hr 19min 25sec

- Cesare Olmi (Bottecchia) @ 2hr 19min 27sec

- Luciano Pezzi (Atala) @ 2hr 20min 48sec

- Ivo Baronti (Bartali) @ 2hr 24min 48sec

- Donato Piazza (Bianchi) @ 2hr 29min 45sec

- José Vidal-Porcar (Spain-Fiorelli) @ 2hr 38min 50sec

- Annibale Brasola (Torpado) @ 2hr 54min 15sec

- Walter Diggelmann (Switzerland-Guerra) @ 2hr 54min 25sec

- Aldo Bini (Bartali) @ 2hr 56min 31sec

- Adri Suykerbuyk (Holland) @ 3hr 2min 2sec

- Hein Van Breenen(Holland) @ 3hr 5min 24sec

Climbers' Competition:

Pasquale Fornara (Bottecchia)

Pasquale Fornara (Bottecchia)- Fausto Coppi (Bianchi)

- Gino Bartali (Bartali)

Winning Team: Ganna Ursus

1953 Giro stage results with running GC:

Stage 1: Tuesday, May 12, Milano - Abano Terme, 263 km

- Wim Van Est: 6hr 37min 10sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 37sec

- Alfo Ferrari @ 2min 52sec

- Elio Brasola s.t.

- Oreste Conte s.t.

- Giorgio Albani s.t.

- Bruno Monti with 93 riders at same time and placing

Stage 2: Wednesday, May 13, Abano Terme - Rimini, 278 km

![]() Major ascent: San Marino

Major ascent: San Marino

- Pasquale Fornara: 7hr 48min 0sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 10sec

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Louison Bobet s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Elio Brasola s.t.

- Guido De Santi s.t.

- Giovanni Corrieri and 21 other riders 3min 7sec

GC after Stage 2:

- Guido De Santi: 14hr 26min 57sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 5sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 1min 15sec

- Fausto Coppi, Louison Bobet, Gino Bartali, Elio Brasola s.t.

- Wim Van Est @ 1min 20sec

Stage 3:

- Albino Crespi: 5hr 3min 23sec

- Wout Wagtmans s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- Michele Gismondi s.t.

- Giuseppe Buratti s.t.

- Agostino Coletto s.t.

- Donato Piazza and the rest of the peloton @ 3min 27sec

GC after Stage 3:

- Guido De Santi: 19hr 33min 47sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1mn 5sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 1min 15sec

- Fausto Coppi, Louison Bobet, Gino Bartali, Elio Brasola s.t.

- Wim Van Est @ 1min 20sec

- Angelo Conterno, Agostino Coletto @ 3min 4sec

Stage 4: Friday, May 15, San Benedetto del Tronto - Roccaraso, 171 km

![]() Major ascent: Cinque Miglia

Major ascent: Cinque Miglia

- Fausto Coppi: 5hr 22min 38sec

- Giorgio Albani s.t.

- Louison Bobet s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Fiorenzo Magni s.t.

- Pasquale Fornara s.t.

- Donato Zampini, Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Pasquale Fornara: 24hr 57min 30sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 10sec

- Louison Bobet, Hugo Koblet, Gino Bartali, Elio Brasola s.t.

- Guido De Santi @ 26sec

- Stan Ockers @ 3min 7sec

- Donato Zampini, Raphaël Géminiani, Elio Brasola, Jean Bobet, Roger Pontet, Ettore Milano, Andrea Carrea s.t.

Stage 5: Saturday, May 16, Roccaraso - Napoli, 149 km

- Ettore Milano: 4hr 1min 16sec

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- Thijs Roks s.t.

- Walter Serena s.t.

- Armando Barducci s.t.

- Cesare Olmi s.t.

- Roger Pontet s.t.

- Marcello Pellegrini s.t.

- Rino Benedetti @ 2min 42sec with 76 riders at same time and place

GC after Stage 5:

- Pasquale Fornara: 29hr 1min 28sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 10sec

- Louison Bobet, Hugo Koblet, Gino Bartali, Elio Brasola s.t.

- Wim Van Est @ 15sec

- Ettore Milano @ 25sec

- Roger Pontet s.t.

- Guido De Santi @ 26sec

Stage 6: Sunday, May 17, Napoli - Roma, 285 km

- Giuseppe Minardi: 8hr 14min 18sec

- Luciano Maggini s.t.

- Pietro Giudici s.t.

- Fritz Schaer s.t.

- Antonio Bevilacqua s.t.

- Tranquillo Scudellaro s.t.

- Guido De Santi s.t.

- Bruno Monti with 85 riders @ 2min 17sec

GC after Stage 6:

- Guido De Santi: 37hr 16min 12sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 51sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 2min 1sec

- Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi, Louison bobet, Elio Brasola s.t.

- Wim Van Est @ 2min 6sec

- Ettore Milano, Jean Pontet @ 2min16sec

Stage 7: Monday, May 18, Roma - Grosseto, 178 km

- Giovanni Corrieri: 5hr 13min 35sec

- Alfredo Martini s.t.

- Annibale Brasola s.t.

- Fiorenzo Crippa s.t.

- Arrigo Padovan s.t.

- Waldemaro Bartolozzi s.t.

- Mario Lorenzotti s.t.

- Hugo Koblet @ 7min 11sec with 88 other riders

GC after Stage 7:

- Giovanni Corrieri

Stage 8: Monday, May 18, Grosseto - Follonica 46 km individual time trial

- Hugo Koblet: 1hr 12min 1sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 46sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 21sec

- Guido De Santi @ 2min 27sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 2min 49sec

- Louison Bobet @ 3min 25sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 31sec

- Gino Bartali @ 3min 43sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 4min 14sec

- Elio Brasola @ 4min 27sec

GC after Stage 8:

- Hugo Koblet: 43hr 50min 30sec

- Guido De Santi @ 23sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 36sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 21sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 2min 43sec

- Louison Bobet @ 3min 26sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 37sec

- Gino Bartali @ 3min 43sec

- Elio Brasola @ 4min 27sec

- Ettore Milano @ 5min 43sec

Stage 9: Tuesday, May 19, Follonica - Pisa, 114 km

- Rik Van Steenbergen: 2hr 59min 31sec

- Fritz Schaer s.t.

- Luciano Pezzi s.t.

- Mario Gestri s.t.

- Adri Suykernuyck s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 47sec

- Donato Piazza s.t.

- Nino Defilippis s.t.

- Luciano Maggini @ 2min 15sec with 88 riders at same time

GC after Stage 9:

- Hugo Koblet: 46hr 51min 46sec

- Guido De Santi @ 26sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 36sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 21sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 2min 43sec

- Louison Bobet @ 3min 26sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 37sec

- Gino Bartali @ 3min 43sec

- Elio Brasola @ 4min 27sec

- Ettore Milano @ 5min 43sec

Stage 10: Thursday, May 21, Pisa - Modena, 189 km

![]() Major ascent: Abetone

Major ascent: Abetone

- Fiorenzo Magni: 5hr 10min 3sec

- Arrigo Padovan s.t.

- Giorgio Albani s.t.

- Pietro Giudici s.t.

- Agostino Coletto s.t.

- Silvio Pedroni s.t.

- Vittorio Rossello s.t.

- Alfredo Pasotti @ 42sec

- Giuseppe Minardi @ 45sec

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Hugo Koblet: 52hr 2min 34sec

- Guido De Santi @ 26sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 36sec

- Fausto Coppi 2 1min 21sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 37sec

- Gino Bartali @ 3min 43sec

- Elio Brasola @ 4min 27sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 5min 27sec

- Alfredo Martini @ 6min 33sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 7min 15sec

Stage 11: Friday, May 22, Modena Autodrome 30 km team time trial

- Bianchi (Coppi, Milano, Gaggero, Gismondi): 27min 45sec

- Ganna (Magni, Baroni, Isotti, Pedroni, Salimbeni, Vincenzo Rossello) @ 1sec

- Legnano (Minardi, Albani, Defilippis, Barducci, Benedetti, Scudellaro) @ 11sec

- Switzerland-Guerra (Koblet, Schaer, Pianezzi, Diggelmann) @ 26sec

- France (Louison Bobet, Géminiani, Coste, Pontet, Vivier) @ 39sec

- Holland (Dikkers, Suykerbuyck, Peters, Van Est) @ 47sec

- Belgium-Girardengo (Van Steenbergen, Ockers, De Gravelyn, Mollin, Gysellinck) @ 1min 5sec

- Welter (Martini, Pellegrini, Pasotti, Serena) @ 1min 12sec

- Leviere (Zampini, Del Santi, Pettinati) @1min 17sec

- Bottecchia (Fornara, Conte, Roma, Zuliani) @ 1min 26sec

GC after Stage 11:

- Hugo Koblet: 52hr 40min 55sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 38sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Elio Brasola @ 5min 37sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 6min 20sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 6min 50sec

- Alfredo Martini @ 7min 19sec

Stage 12: Saturday, May 23, Modena - Genova, 278 km

- Giorgio Albani: 8hr 33min 22sec

- Raphaël Géminiani s.t.

- Nino Defilippis s.t.

- Donato Zampini s.t.

- Bruno Monti s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- Pietro Giudici s.t.

- Agostino Coletto s.t.

- Vittorio Rossello s.t.

- Stan Ockers @ 1min 13sec

GC after Stage 12:

- Hugo Koblet: 61hr 15min 50sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 58sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Elio Brasola @ 6min 27sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 6min 29sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 6min 50sec

- Alfredo Martini @ 7min 19sec

Stage 13: Sunday, May 24, Genova - Bordighera, 256 km

![]() Major ascent: Turchino

Major ascent: Turchino

- Oreste Conte: 8hr 35min 6sec

- Mario Baroni s.t.

- Giovanni Corrieri s.t.

- Donato Piazza s.t.

- Dante Rivola s.t.

- Alfredo Pasotti and the rest of the peloton @ s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Hugo Koblet: 69hr 50min 58sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Paquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 58sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Elio Brasola @ 6min 27sec

- Giovanni Corrieri @ 6min 29sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 6min 50sec

- Alfredo Martini @ 7min 19sec

Stage 14: Monday, May 25, Bordighera - Torino, 241 km

- Pietro Giudici: 7hr 6min 4sec

- Fritz Schaer s.t.

- Michele Gismondi @ 6sec

- Mario Baroni s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- Alfredo Pasotti s.t.

- Serafino Biagioni s.t.

- Vincenzo Rossello s.t.

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Roger Buchonnet s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Hugo Koblet: 77hr 2min 38sec

- Faustoi Coppi @ 56sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 2min 48sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 2min 55sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 36sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 5min 7sec

- Elio Brasola @ 6min 27sec

Stage 15: Tuesday, May 26, Torino - San Pellegrino, 232 km

- Nino Assirelli: 6hr 10min 49sec

- Danilo Barossi @ 1min 47sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 2min 24sec

- Oreste Conte s.t.

- Mario Ciabatti s.t.

- Fritz Schaer s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- José Vidal-Porcar s.t.

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Hugo Koblet: 83hr 15min 33sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 2min 48sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 2min 55sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 58sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 6min 7sec

- Elio Brasola @ 6min 27sec

Stage 16: Thursday, May 28, San Pellegrino - Riva del Garda, 279 km

![]() Major ascent: Tonale

Major ascent: Tonale

- Fiorenzo Magni: 8hr 34min 50sec

- Giorgio Albani s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Fritz Schaer s.t.

- Fausto Coppi and 20 other riders @ s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Hugo Koblet: 91hr 50min 43sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido Se Danti @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 2min 48sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 2min 55sec

- Wim Van Est @ 3min 58sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 6min 7sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 6min 50sec

Stage 17: Friday, May 29, Riva del Garda - Vicenza, 166 km

- Bruno Monti: 4hr 34min 16sec

- Danilo Barozzi s.t.

- Agostino Coletto s.t.

- Aldo Zuliani @ 10sec

- Mario Baroni @ 21sec

- Annibale Brasola @ 28sec

- Rik Van Steenbergen s.t.

- Nino Defilippis @ 1min 51sec

- Stan Ockers with the rest of the peloton except Valerio Bonini @ s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Hugo Koblet: 96hr 26min 50sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 55sec

- Guido De Santi @ 1min 17sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 1min 36sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 2min 48sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 2min 55sec

- Wim Van Est @ 2min 58sec

- Gino Bartali @ 4min 52sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 6min 7sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 6min 50sec

Stage 18: Saturday, May 30, Vicenza - Auronzo, 186 km

- Bruno Monti: 5hr 21min 15sec

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Raphaël Géminiani @ 29sec

- Stan Ockers 2 41sec

- Rinaldo Moresco @ 1min 4sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Wim Van Est and 22 riders @ s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Hugo Koblet: 101hr 48min 5sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 59sec

- Guido De Santi @ 2min 21sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 2min 40sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 3min 52sec

- Fritz Schaer @ 3min 59sec

- Wim Van Est @ 5min 2sec

- Gino Bartali @ 5min 56sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 7min 11sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 7min 54sec

Stage 19: Sunday, May 31, Auronzo - Bolzano, 164 km

![]() Major ascents: Misurina, Falzarego, Pordoi, Sella

Major ascents: Misurina, Falzarego, Pordoi, Sella

- Fausto Coppi: 5hr 19min 29sec

- Hugo Koblet s.t.

- Pasquale Fornara @ 3min 56sec

- Donato Zampini @ 7min 23sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Nino Defilippis @ 8min 54sec

- Vincenzo Rossello @ 9min 26sec

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Pietro Giudici s.t.

- Danilo Barossi s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Hugo Koblet: 107hr 7min 34sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1mn 59sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 6min 36sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 13min 16sec

- Gino Bartali @ 13min 19sec

- Guido De Santi @ 15min 4sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 16min 37sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 17min 28sec

- Stan Ockers @ 18min 29sec

- Vincenzo Rossello @ 19min 2sec

Stage 20: Monday, June 1, Bolzano - Bormio, 125 km

![]() Major ascent: Stelvio

Major ascent: Stelvio

- Fausto Coppi: 4hr 51min 32sec

- Pasquale Fornara @ 2min 18sec

- Gino Bartali @ 2min 48sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 3min 28sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 4min 5sec

- Donato Zampini @ 5min 38sec

- Agostino Coletto @ 7min 43sec

- Pietro Giudici @ 7min 44sec

- Stan Ockers s.t.

- Andrea Carrea @ 9min 3sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Fausto Coppi: 112hr 1min 5sec

- Hugo Koblet @ 1min 29sec

- PAsquale Fornara @ 6min 55sec

- Gino Bartali @ 14min 8sec

- Angelo Conterno @ 20min 51sec

- Stan Ockers @ 24min 14sec

- Giovanni Roma @ 24min 35sec

- Guido De Santi @ 25min 6sec

- Fiorenzo Magni @ 25min 39sec

- Vincenzo Rossello @ 26min 21sec

21st and Final Stage: Tuesday, June 2, Bormio - Milano, 220 km

- Fiorenzo Magni: 6hr 36min 0sec

- Luciano Maggini s.t.

- Ivo Baronti s.t.

- Donato Piazza s.t.

- Aldo Bini s.t.

- Annibale Brasola s.t.

- Dante Rivola s.t.

- Wim Van Est s.t.

- Bruno Monti s.t.

- Stan Ockers s.t.

Complete Final 1953 Giro d'Italia General Classification

The Story of the 1953 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 1. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

The Giro again attracted a spectacular field of riders: Coppi, Ockers, van Steenbergen, Bobet, Géminiani, Ruiz, Koblet (in superb form), Kübler (in questionable shape), Schaer, Astrua, Bartali, Magni and Defilippis. The Swiss, French, Belgian, Dutch and Spanish riders were placed in national teams sponsored by Italian bike companies with the Italians racing in their normal trade-team colors. Because the French bike companies had limited funds for their teams, during the fifties they regularly allowed their riders to sign and ride for two teams, one for northern European races and another for Italian competitions. Louison Bobet’s brother Jean wrote that riding for the Italian teams was a wondrous luxury, with their superior team support, technical knowledge and equipment. He remembered Clément tires with especial fondness. So do I.

What happens to a rider after he can no longer make a living racing? Some open bars, other go back to their farms or factory jobs and some end up working for professional teams. A few of the great Giro riders of the past who directed teams in this Giro will be familiar to the reader:

Belgium: Costante Girardengo

Switzerland: Learco Guerra

Atala: Alfredo Sivocci

Bottecchia: Giordano Cottur

Legnano: Eberardo Pavesi

The 4,035 kilometer route was divided into 21 stages, yielding a 192 kilometer-per-stage average, considerably longer than Valetti’s 161-kilometer average in 1939 but a bit shorter than Magni’s 208 of 1948.

Showing that Italy was getting richer and communications technology was advancing, for the first time some of the Giro’s finishes were televised live rather than filmed to be broadcast later.

The 1953 edition would end with a flourish. In addition to the usual Dolomite stage with the Misurina, Falzarego, Pordoi and Sella passes, the penultimate stage had the Giro’s first crossing of the Stelvio Pass.

Hacked out of the mountains by 2000 workers in the early 1820s, its 48 switchbacks were paved with stones in 1938 (it’s asphalted now). Visually the pass is stunning because a lot of it is above the tree line and much of it can be seen from its crest. Sports writers called the massive climb the montagna di troppo, literally, the mountain that is too much. Of Europe’s paved passes, only the Iseran in France goes higher. Like France’s Alpe d’Huez, it holds an iconic place in cycling’s heart. But the Stelvio is so much grander, so much bigger.

The Giro’s route led the riders out of Milan and down the Adriatic side of Italy. Kübler, in poor condition and unable to stay with the peloton, didn’t even finish the first stage. Teammate Rolf Graf waited for him and both abandoned.

Partway through the fourth stage to Roccaraso, southeast of Rome, Koblet crashed into a little girl who had just gathered some wildflowers to toss at the peloton. As Koblet was speeding around a curve chasing an attacking Vincenzo Rossello, she jumped in front of Koblet to grab the musette that Rosello had dropped moments earlier and the two collided. The little girl was OK but Koblet was knocked out cold. Revived, he was addled from the crash and his bike was destroyed. The Swiss team members got their leader up and on another bike and proceeded to chase the peloton. Schaer buried himself for twenty kilometers to bring his captain up to the leaders.

Meanwhile, in a surprising display of sportsmanship, the leading riders (Coppi and Bobet in particular), having learned that Koblet was chasing, stopped racing and rode slowly until Koblet made contact. He arrived with a torn and bloody jersey and sporting a bandage on his head. The reader has seen that the normal impulse of this and earlier eras had been to use a rider’s misfortune to deliver a coup de grace and I’m sure Koblet expected to have been handled roughly after his crash. But it didn’t happen. This might be the first instance in Giro history of such generous riding.

At Roccaraso, Coppi was first across the line followed by Albani, Bobet, Bartali, Ockers, Koblet, Magni and Pasquale Fornara. Fornara got to wear pink for a couple of stages but he was traveling with a tough bunch.

The eighth stage time trial came after the riders had gone as far south as Naples and raced back up to Tuscany. The 48.5-kilometer test showed how fine Koblet’s condition really was and that his stage four crash hadn’t cause any lasting ill-effects. Before the Follonica time trial Coppi, Koblet, Bartali and Bobet had been tied. Koblet won the stage and took the lead. Coppi was 81 seconds back, Magni lost almost three minutes, Bobet three and a half. Koblet now had a narrow lead in the General Classification:

1. Hugo Koblet

2. Guido de Santi @ 23 seconds

3. Pasquale Fornara @ 36 seconds

4. Fausto Coppi @ 1 minute 21 seconds

5. Giovanni Corrieri @ 2 minutes 43 seconds

6. Louison Bobet @ 3 minutes 26 seconds

Also riding on the French team was Louison Bobet’s brother Jean, a fairly good pro. He wrote about that time trial and what it was like when Coppi passed him: “He had arrived. He passed me on the left. He did not notice me. He was riding on a cushion of air. His long legs were whirling round and his hands on top of the handlebars. He was sublime…One day, in a cloud of golden dust, I saw the sun riding a bicycle between Grosseto and Follonica.” This from a fellow professional who had raced against the best.

Four days later the Giro held a 30-kilometer team time trial on the Modena autodrome, which ended up tightening the race still further. Bianchi won the stage with Magni’s Ganna squad only a single second slower. Since Magni was down seven minutes, Ganna’s good ride didn’t change things. Koblet’s Swiss team lost only 26 seconds, letting Koblet remain in the lead. But Coppi was now only 55 seconds back. Given Coppi’s ability to regain time on a good day, 55 seconds was, in the words of French racer Bernard Thévenet, but a puff of air.

The race warmed on the eighteenth stage. Koblet was a complete rider and he proved it by escaping on a descent with Bruno Monti and Rino Benedetti, beating the Coppi group by a minute. Koblet now had 1 minute 59 seconds on Coppi. A bigger puff of air?

The nineteenth stage had those four major passes to cross, the Misurina, Falzarego, Pordoi and Sella before finishing on the track in Bolzano. Koblet got away on Coppi’s climb, the Pordoi. Coppi regained contact on the Sella and then dropped the Swiss rider. Again, Koblet descended with skill and without fear to close the gap. The riders came into the velodrome together with Coppi leading. When Coppi stood up to sprint there was nothing Koblet could do. Coppi easily won the stage by several lengths. The officials were generous and gave Koblet the same time, probably assuming Koblet let Coppi have the stage in the classic deal where the Classification leader gives his breakaway companion the consolation prize of the stage win. Coppi generously told Koblet, “My compliments, the Giro is yours. You are the strongest.” Koblet felt that Coppi was conceding the Giro to him at this point. Maybe he was and maybe Coppi was being nothing more than an Italian gentleman.

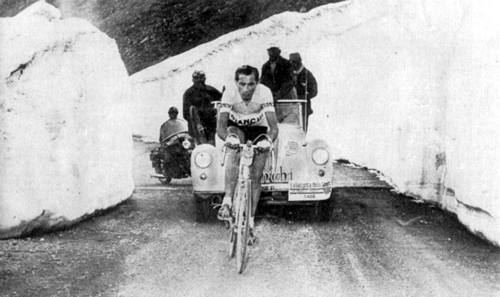

Fausto Coppi leads Hugo Koblet, probably in stage 19.

The General Classification now stood thus:

1. Hugo Koblet

2. Fausto Coppi @ 1 minute 59 seconds

3. Pasquale Fornara @ 6 minutes 36 seconds

Koblet appeared to have a firm hold on the lead with only two stages left. But the next stage with its ascent of the Stelvio is one of the most famous in cycling history. It wasn’t a long stage, only 125 kilometers. But the Stelvio’s 7.5 percent average gradient is especially difficult because it never flattens out. A rider cannot coast or rest for even one moment because his bike will just stop.

We’ve seen that Coppi was a complicated man, and when his morale was down or he was distracted, he wouldn’t prosecute a race to the fullest of his ability, if at all. Without Serse, this was an even larger problem. So far the 1953 Giro had been just such a case. Koblet had been on fire while Coppi had been irresolute. His team knew that if they could motivate Coppi for the Stelvio stage, the Giro and a big pot of race winnings would be theirs.

All of the Bianchi team, even company boss Zambrini, began a campaign to convince Coppi that Koblet could be beaten on the Stelvio and Coppi could still win the Giro. Coppi resisted these efforts, saying that the Giro was over and then went to bed.

The next morning the team was at it again. One of his gregari, Ettore Milano, reminded Coppi that Koblet often raced poorly in the highest passes. It doesn’t seem to have helped.

Before the stage start, Milano went over to see if he could detect signs that Koblet had overdone the amphetamines for the previous Dolomite stage. Had Koblet been a member of what was called the “staring at the ceiling club”? A rider who wasn’t careful about how much of the drug he had taken would have a rough, sleepless night and be ill-prepared for the next day’s racing. The top pros generally needed and used smaller doses of stimulants, allowing them to metabolize the drugs in time for bedtime, while the lesser-talented riders who required more help would suffer the post-race torture that awaited them in the evening. Milano wanted proof for his boss that Koblet had taken too much dope. He approached Koblet and told him that he wanted to take a picture of him, and thus got the Swiss rider to remove his dark glasses. Koblet’s face revealed his dilated pupils and haggard look, evidence of his amphetamine overuse.

Milano assured Coppi that indeed Koblet was a mess and had probably taken a heavy dose again that morning because of the appearance of his pupils and obvious thirst. Amphetamines can cause dry mouth; hence Koblet’s constant sipping of water before the race start.

Coppi answered Milano in a way that indicated that he too was feeling the effects from taking amphetamines. As an aside, another amphetamine side-effect is hyperthermia. Racers with a butt-load of speed can’t tolerate heat but often do well in the cold, as we’ll see later.

Early on the ascent Koblet indeed seemed to be in some difficulty. Almost the entire field had been dropped but Coppi remained indecisive. Still, he told his best and only remaining gregario, Andrea “Sandrino” Carrea, to set a red-hot pace. After Carrea had given his all, Koblet was still there along with Fornara, Bartali (now 39 years old!) and, incredibly, Defilippis. Coppi asked Defilippis to attack (Coppi called him Cit, Piedmontese for “kid”), which he did, creating a gap which Coppi did not close. But Koblet did. It was an amateurish move on his part because Defilippis was no threat, being down more than a half hour. But in expending the energy to make contact with Defilippis, he made himself vulnerable to a counter-attack. Coppi delivered his blow with overwhelming force. He just flew away; no one could stay with him. Defilippis said he went like a motorcycle; he had never seen anything like the way Coppi rode away from him up the Stelvio.

Part way up the mountain Coppi spotted Giulia Locatelli standing by the side of the road. She had come to watch the stage, this time without her husband. He asked her if she were going to be in Bormio, where the stage ended. Locatelli, who would come to be known as “the Woman in White” because of the coat she was photographed wearing, answered in the affirmative. Now Coppi was really on fire. Past the walls of snow and ice that lined the road Coppi rode. Watching a film of that ride, seeing Coppi’s utter mastery of the bike, his smoothness climbing the insanely difficult mountain left me open-mouthed in wonder.

Fausto Coppi on the Stelvio

The south face of the Stelvio presents a challenging descent, but Koblet’s usual mastery of the skill deserted him that day, probably from a mixture of drugs, sleeplessness and desperation. He crashed twice and flatted at least once.

Coppi rode into Bormio 2 minutes 18 seconds ahead of Pasquale Fornara and 3 minutes 28 seconds in front of Koblet. Defilippis said that if Koblet had just stayed with Coppi rather than answer his attack, he would have kept the maglia rosa.

Coppi had won the Giro.

Coppi and Koblet stayed in the same hotel that evening and even crossed paths in a corridor, yet not a word was spoken between them; Koblet glared at Coppi and then entered his room, slamming the door.

There was only the final stage to Milan finishing in the Vigorelli, which Magni won. Coppi had at last matched Binda’s record of five Giro wins.

Final 1953 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Fausto Coppi (Bianchi) 118 hours 37 minutes 26 seconds

2. Hugo Koblet (Switzerland-Guerra) @ 1minute 29 seconds

3. Pasquale Fornara (Bottecchia) @ 6 minutes 55 seconds

4. Gino Bartali (Bartali) @ 14 minutes 8 seconds

5. Angelo Conterno (Frejus) @ 20 minutes 51 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Pasquale Fornara (Bottecchia)

2. Fausto Coppi (Bianchi)

3. Gino Bartali (Bartali)

Coppi didn’t ride the Tour that year. Writers give a number of conflicting reasons as to why he chose not to use his fabulous form to try for another Giro-Tour double. Cycling journalist Sven Novrup writes that the Tour management had the final say in teams chosen and that after Coppi’s total domination of the 1952 edition (to keep the riders competing, Tour management had doubled the prizes for second and third place) they simply did not invite him. Perhaps this was similar to the Giro’s not wanting Binda in their race 23 years before.

Others write that Coppi wouldn’t race the Tour if Bartali were included in the Italian team. This seems unlikely given Bartali’s generous help in the Tour the year before. Another reason given is that the one big prize that had so far eluded Coppi was a rainbow jersey. He wanted to skip the Tour to prepare for the world championship race to be held that August just over the border in Lugano, Switzerland.

Then there is Giulia Locatelli. After the Giro Coppi had begun a real affair with her and some suppose he wanted to spend time with her. Tour scholar Owen Mulholland thinks that none of the reasons is wrong and that they should be taken in their totality to explain Coppi’s missing the 1953 Tour.

Coppi’s preparation for the World Championship was good enough for a solo finish, a full six and a half minutes ahead of second-place Germain Derycke. He had at last captured the elusive rainbow jersey.

Coppi’s famous blind masseur Biagio Cavanna continued to work with and advise Coppi. Over his career he had cared for some of the greatest champions and was confident of his abilities to judge cycling talent. When Jacques Anquetil met Coppi and Cavanna before the 1953 Baracchi Trophy two-man time trial, the nineteen-year old Frenchman submitted himself to Cavanna’s touch. The masseur said that Anquetil’s body was much like Coppi’s and that if he were to be resolute and careful in his training, diet and lifestyle he could have an excellent career in professional racing. Anquetil left, deciding to ignore Cavanna’s advice to lead an ascetic life. Indeed he did!

Coppi, Koblet, Kübler and Louison Bobet formed a group Bobet’s brother Jean later came to call cycling’s “G4”. These rulers of the peloton had social aspirations that had them driving expensive cars (Koblet owned an American Studebaker), wearing tailored clothes and exhibiting manners that sometimes made them the butt of jokes from their more earthy professional cycling workmates. Rik van Steenbergen, by dint of his stature as the premier Classics rider of his era, should have gained entrance to this select group, but he was excluded be cause he was a bit too rustic and in Jean Bobet’s words, too much of the rough Belgian flahute.

.