1940 Giro d'Italia

28th edition: May 17 - June 9

Results, stages with running GC, photos and history

1939 Giro | 1941-45 Giri | Giro d'Italia Database | 1940 Giro Quick Facts | 1940 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | Teams | The Story of the 1940 Giro d'Italia

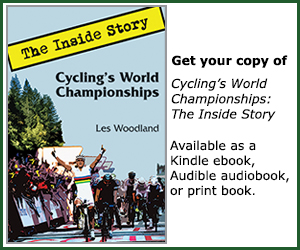

Map of the 1940 Giro d'Italia

Les Woodland's book The Olympics' 50 Craziest Stories: A Five Ring Circus is available in print, Kindle eBook & audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

3,574 km raced at an average speed of 33.24 km/hr

91 starters and 47 classified finishers.

Gino Bartali was the leader of the Legnano team at the race's start, but he crashed and lost time in the second stage. A new gregario hired to help Bartali, Fausto Coppi, became the team leader.

In stage eleven, Coppi attacked on the Abetone pass and at the end of the stage became the maglia rosa.

Despite some trouble in the high mountains, Coppi won his first of five Giri and became the youngest-ever Giro winner.

Another map of the 1940 Giro d'Italia

![]() 1940 Giro d'Italia Final General Classification:

1940 Giro d'Italia Final General Classification:

- Fausto Coppi (Legnano): 107hr 31mn 10sec

- Enrico Mollo (Olympia) @ 2min 40sec

- Giordano Cottur (Lygie) @ 11min 45sec

- Mario Vicini (Bianchi) @ 16min 27sec

- Severino Canavesi (Gloria) @ 16min 50sec

- Ezio Cecchi (Gloria) @ 22min 30sec

- Walter Generati (Gloria) @ 25min 3sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis (Dop. Azzini Bamberg) @ 27min 50sec

- Gino Bartali (Legnano) @ 46min 9sec

- Settimo Simonini (U.S. Azzini-Universal) @ 48min 37sec

- Walter Diggelmann (Olympia) @ 49min 26sec

- Michele Benente (Gerbi) @ 49min 43sec

- Bernardo Rogora (Gloria) @ 53min 14sec

- Adriano Vignoli (Comando Generale MVSM-Viscontea) @ 58min 46sec

- Diego Marabelli (GS Battisti-Aquilano) @ 1hr 5min 18sec

- Salvatore Crippa (Gerbi) @ 1hr 22min 3sec

- Giovanni Valetti (Bianchi) @ 1hr 34min 13sec

- Cesare Del Cancia (Comando Generale MVSM-Viscontea) @ 1hr 34min 14sec

- Mario De Benedetti (Dop. Az. Bamberg) @ 1hr 42min 48sec

- Francesco Patti (Il Littoriale) @ 1hr 45min 53sec

- Primo Volpi (U.S. Azzini-Universal) @ 1hr 48min 41sec

- Glauco Servadei (Gloria) @ 1hr 52min 5sec

- Fulvio Montini (SS Parioli) @ 1hr 52min 9sec

- Aimone Landi (Lygie) @ 2hr 0min 8sec

- Edoardo Stretti (Dop. Az. Vismara) @ 2hr 1min 50sec

- Secondo Magni (Dop. AZ. Vismara) @ 2hr 11min 26sec

- Augusto Introzzi (Gloria) @ 2hr 18min 2sec

- Adolfo Leoni (Legnano) @ 2hr 18min 20sec

- Guerrino Amadori (GS Battisti-Aquilano) @ 2hr 19min 33sec

- Alessandro Vegetti (US Azzini-Universal) @ 2hr 25min 11sec

- Sebastiano Torchio (Gerbi) @ 2hr 26min 21sec

- Giovanni Brotto (Dopolavoro Mater) @ 2hr 31min 36sec

- Giuseppe Magni (Dop. Az. Vismara) @ 2hr 38min 43sec

- Ennio Pozzato (UC Modenese) @ 2hr 39min 8sec

- Gildo Monari (UC Modenese) @ 2hr 41min 54sec

- Edgardo Scappini (Comando Generale MVSM-Viscontea) @ 2hr 46min 14sec

- Enrico Mara (GS Battisti-Aquilano) @ 2hr 53min 35sec

- Marcello Spadolini (Dopolavoro Mater) @ 2hr 53min 56sec

- Lorenzo Mazzarello (Gerbi) @ 3hr 7min 6sec

- Aldo Ronconi (Legnano) @ 3hr 12min 16sec

- Francesco Doccini (US Azzini-Universal) @ 3hr 20min 20sec

- Giuseppe Colombara (Dop. Az. Bamberg) @ 3hr 24min 32sec

- Pietro Rimoldi (Olympia) @ 3hr 45min 35sec

- Pietro Chiappini (Lygie) @ 3hr 56min 32sec

- Egidio Facchin (Il Littoriale) @ 4hr 6min 2sec

- Gino Scappini (US Azzini-Universal) @ 4hr 8min 5sec

- Francesco Albani (Lygie) @ 4hr 16min 6sec

![]() Climbers’ Competition:

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Gino Bartali (Legnano)

2. Fausto Coppi (Legnano)

3. Enrico Mollo (Olympia)

Team Classification:

- Gloria: 306hr 14min 23sec

- Legnano @ 1hr 51min 40sec

- Bianchi @ 3hr 30min 57sec

- Gerbi @ 3hr 32min 44sec

- Olympia @ 3hr 33min 18sec

- Lygie @ 5hr 3min 30sec

1940 Giro stage results with running GC:

Stage 1: Friday, May 17, Milano - Torino, 180 km

- Olimpio Bizzi: 4hr 58min 4sec

- Gino Bartali @ 2min 1sec

- Osvaldo Bailo s.t.

- Aldo Bini s.t.

- Marcello Spadolini s.t.

- Pierino Favalli s.t.

- 28 riders at same time and placing

Stage 2: Saturday, May 18, Torino - Genova, 226 km

- Pierino Favalli: 6hr 11min 44sec

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Osvaldo Bailo s.t.

- Mario Ricci s.t.

- Fulvio Montini s.t.

- Giovanni Gotti s.t.

- Giovanni Cazzulani s.t.

- Settimo Simonini s.t.

- Primo Zuccotti s.t.

- Adriano Vignoli s.t.

24. Gino Bartali @ 5min 15sec

GC after Stage 2:

- Osvaldo Bailo: 11hr 11min 49sec

- Pierino Favalli s.t.

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Fulvio Montini s.t.

- Primo Zuccotti s.t.

- Adriano Vignoli s.t.

- Gildo Monari @ 11sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 2min 1sec

- Bernardo Rogora s.t.

- Giordano Cottur @ 2min 8sec

Stage 3: Sunday, May 19, Genova - Pisa, 288 km

- Diego Marabelli: 5hr 27min 7sec

- Mario Vicini s s.t.

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Christophe Didier s.t.

- Giuseppe Magni s.t.

- Enrico Mollo @ 7sec

- Ennio Pozzato @ 36sec

- Francesco Doccini s.t.

- Giovanni Di Santi @ 1min 5sec

- 27 riders all at same time and placing

GC after Stage 3:

- Osvaldo Bailo: 16hr 40min 9sec

- Pierino Favalli s.t.

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Giordano Cottur @ 55sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 5sec

- Christophe Didier @ 1min 30sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 2min 1sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 3min 12sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 3min 14sec

- Mari Vicini @ 4min 2sec

Stage 4: Monday, May 20, Pisa - Grosseto, 154 km

- Adolfo Leoni: 4hr 12min 35sec

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Pietro Rimoldi s.t.

- Wlater Diggelmann s.t.

- Edgardo Scappini s.t.

- Pierino Favalli s.t.

- Walter Generati s.t.

- Alessandro Vegetti s.t.

- Aimone Landi s.t.

- Gildo Monari s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Pierino Favalli: 20hr 52min 44sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 4sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 5sec

- Christophe Didier @ 1min 30sec

- Severino Canvesi @ 2min 1sec

- Walter Generati @ 5min 13sec

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 15sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 7min 31sec

- Gildo Monari @ 7min 36sec

Stage 5: Tuesday, May 21, Grosseto - Roma, 264 km

- Adolfo Leoni: 6hr 34min 50sec

- Serafino Santambrogio s.t.

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Aldo Bini @ 50sec

- Spirito Godio s.t.

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

- Francesco Albani s.t.

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Nello Taddei s.t.

- 62 riders at same time and placing

GC after Stage 5:

- Pierino Favalli: 34hr 39min 49sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 4sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 5sec

- Christophe Didier @ 1min 30sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 2min 1sec

- Walter Generati @ 5min13sec

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 15sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 7min 31sec

- Bernardo Rogora @ 9min 26sec

Stage 6: Thursday, May 23, Roma - Napoli, 238 km

- Glauco Servadei: 7hr 11min 25sec

- Quirino Toccacelli s.t.

- Olimpio Bizzi s.t.

- Pietro Rimoldi s.t.

- Pierino Favalli s.t.

- Marcello Spadolini s.t.

- Osvaldo Bailo s.t.

- 52 riders at same time and placing

GC after Stage 6:

- Pierino Favalli: 34hr 39min 49sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 4sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 5sec

- Christophe Didier @ 1min 30sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 2min 1sec

- Walter Generati @ 5min 13sec

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 15sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 7min 31sec

- Bernardo Rogora @ 9min 26sec

Stage 7: Friday, May 24, Napoli - Fiuggi, 178 km

- Walter Generati: 5hr 31min 55sec

- Giovanni Valetti @ 2min 0sec

- Diego Marabelli @ 25sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis s.t.

- Salvatore Crippa @ 35sec

- Quirino Toccacelli s.t.

- Giovanni Di Santi s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t.

- Gildo Monari s.t.

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Pierino Favalli: 40hr 12min 19sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 1min 4sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 5sec

- Christophe Didier @ 1min 30sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 2min 1sec

- Walter Generati @ 4min 38sec

- Glauco Servadei @ 5min 13sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 15sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 7min 31sec

- Bernardo Rogora @ 9min 26sec

Stage 8: Saturday, May 25, Fiuggi - Terni, 183 km

- Olimpio Bizzi: 5hr 24min 24sec

- Walter Diggelmann s.t.

- Salvatore Crippa s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Secondo Magni s.t.

- Diego Marabelli s.t.

- Mario Vicini s.t.

- Remo Cerasa s.t.

- 14 riders at same time and placing

GC after Stage 8:

- Enrico Mollo: 45hr 37min 48sec

- Christophe Didier @ 25sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 54sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 3min 7sec

- Walter Generati @ 3min 33sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 4min 10sec

- Pierino Favalli @ 5min 56sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 6min 26sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 9min 16sec

- Settimo Simonini @ 9min 44sec

Stage 9: Sunday, May 26, Terni - Arezzo, 183 km

- Primo Volpi: 5hr 22min 44sec

- Olimpio Bizzi s.t.

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Ruggero Moro s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t.

- Aldo Bini s.t.

- Marcello Spadolini s.t.

- Ruggero Balli s.t.

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Enrico Mollo: 51hr 0min 32sec

- Christophe Didier @ 25sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 54sec

- Fuasto Coppi @ 3min 7sec

- Walter Generati @ 3min 33sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 4min 10sec

- Pierino Favalli @ 5min 56sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 6min 26sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 9min 16sec

- Settimo Simonini s.t.

Stage 10: Monday, May 27, Arezzo - Firenze, 91 km

![]() Major ascent: Consuma

Major ascent: Consuma

- Olimpio Bizzi: 2hr 39min 23sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Primo Volpi s.t.

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Mario Vicini s.t.

- Giordano Cottur @ 25sec

- Aladino Mealli s.t.

- Giovanni De Stefanis s.t.

- Severino Canavesi s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Enrico Mollo: 53hr 40min 20sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 56sec

- Fausto Coppi @ 2min 42sec

- Christophe Didier @ 2min 57sec

- Ezi Cecchi @ 4min 30sec

- Walter Generati @ 5min 37sec

- Giovanni Gotti @ 8min 38sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 9min 16sec

- Swettimo Simonini @ 11min 48sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 12min 0sec

Stage 11: Wednesday, May 29, Firenze - Modena, 181 km

Major ascent: Abetone

- Fausto Coppi: 5hr 35min 10sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 3min 45sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Salvatore Crippa s.t.

- Diego Marabelli s.t.

- Walter Giggelmanns.t.

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Christophe Didier s.t.

- Michele Benente s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Fausto Coppi: 59hr 18min 12sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 3sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 3min 46sec

- Christophe Didier @ 4min 0sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 6min 40sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 19sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 13min 3sec

- Gino Bartali @ 15min 4sec

- Mario Vicini @ 15min 38sec

Stage 12: Thursday, May 30, Modena - Ferrara, 199 km

- Adolfo Leoni: 5hr 27min 0sec

- Aimone Landi s.t.

- Sebastiano Torchio s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t.

- Walter Diggelmann s.t.

- Carmine Saponetti s.t.

- Gino Bisio s.t.

- Edgardo Scappini s.t.

- Gino Scappini s.t.

- Franesco Albani @ 2min 36sec

GC after Stage 12:

- Fausto Coppi: 64hr 47min 48sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 3sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 3min 46sec

- Christophe Didier @ 4min 0sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 6min 40sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 19sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 13min 3sec

- Gino Bartali @ 15min 4sec

- Mario Vicini @ 15min 39sec

Stage 13: Friday, May 31, Ferrara - Treviso, 125 km

- Olimpio Bizzi: 3hr 20min 28sec

- Adolfo Leoni s.t.

- Francesco Doccini s.t.

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Sebastiano Torchio s.t.

- Walter Diggelmann s.t.

- Pietro Chiappini s.t.

- Diego Marabelli s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Fausto Coppi: 68hr 8min 16sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 3sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 3min 46sec

- Christophe Didier @ 4min 0sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 6min 40sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 19sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 13min 3sec

- Gino Bartali @ 15min 4sec

- Mario Vicini @ 15min 38sec

Stage 14: Saturday, June 1, Treviso - Abbazia, 215 km

- Glauco Servadei: 6hr 36min 45sec

- Walter Generati s.t.

- Adolfo Leoni s.t.

- Mario Vicini s.t.

- Pietro Chiappini s.t.

- Edgardo Scappini s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t.

- Aimone Landi s.t.

- Primo Zuccotti s.t.

- 52 riders at same time and placing

GC after Stage 14:

- Fausto Coppi: 74hr 45min 1sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 1min 3sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 3min 46sec

- Christophe Didier @ 4min 0sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 5min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 6min 40sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 19sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 13min 3sec

- Gino Bartali @ 15min 4sec

- Mario Vicini @ 15min 38sec

Stage 15: Sunday, June 2, Abbazia - Trieste, 179 km

- Mario Vicini: 5hr 38min 40sec

- Olimpio Bizzi s.t.

- Giordano Cottur @ 2min 4sec

- Enrico Mollo s.t.

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Michele Benente s.t.

- Adriano Vignoli s.t.

- Giovanni De Stefanis @ 8min 10sec

- Settimo Simonini @ 12min 14sec

- Sebastiano Torchio s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Fausto Coppi: 8hr 25min 45sec

- Enrico Mollo 2 1min 3sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 19sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 10min 59sec

- Mario Vicini @ 13min 34sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 14min 3sec

- Christophe Didier @ 16min 22sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 16min 47sec

- Walter Generati @ 16min 57sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis @ 21in 45sec

Stage 16: Tuesday, June 4, Trieste - Pieve di Cadore, 202 km

![]() Major ascent: Mauria

Major ascent: Mauria

- Mario Vicini: 6hr 36min 36sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 2min 57sec

- Enrico Mollo s.t.

- Adolfo Leoni s.t.

- Salvatore Crippa s.t.

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Fausto Coppi @ 3min 1sec

- Vasco Bergamaschi s.t.

- Giovanni De Stefanis s.t.

- Severino Canavesi s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Fausto Coppi: 87hr 5min 22sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 59sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 10min 15sec

- Mario Vicini @ 10min 33sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 10min 55sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 14min 3sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 16min 47sec

- Walter Generati @ 18min 58sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis @ 21min 45sec

- Settimo Simonini @ 32min 23sec

Stage 17: Wednesday, June 5, Pieve di Cadore - Ortisei, 110 km

![]() Major ascents: Falzarego, Pordoi, Sella

Major ascents: Falzarego, Pordoi, Sella

- Gino Bartali: 3hr 50min 30sec

- Fausto Coppi s.t.

- Enrico Mollo @ 2min 13sec

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Severino Canavesi @ 3min 19sec

- Walter Diggelmann @ 4min 59sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 6min 26sec

- Michele Benente s.t.

- Walter Generati @ 6min 37sec

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Fausto Coppi: 90hr 55min 52sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 3min 12sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 12min 28sec

- Mario Vicini @ 17min 10sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 17min 22sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 23min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 25min 35sec

- Olimpio Bizzi @ 28min 6sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis @ 28min 22sec

- Gino Bartali @ 45min 59sec

Stage 18: Friday, June 7, Ortisei - Trento, 186 km

![]() Major ascent: Palade

Major ascent: Palade

- Glauco Servadei: 5hr 48min 28sec

- Adolfo Leoni s.t.

- Enrico Mara s.t.

- Pietro Rimoldi s.t.

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Walter Diggelmanns.t.

- Fulvio Montini s.t.

- Francesco Patti s.t.

- Francesco Albani s.t.

- 31 riders at same time and placing

GC after Stage 18:

- Fausto Coppi: 96hr 44min 20sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 3min 12sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 12min 28sec

- Mario Vicini @ 17min 10sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 17min 22sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 23min 13sec

- Walter Generati @ 25min 35sec

- Giovanni De Stefanis @ 28min 6sec

- Gino Bartali @ 45min 59sec

- Settimo Simonini @ 48min 9sec

Stage 19: Saturday, June 8, Trento - Verona, 149 km

![]() Major ascent: Pian della Fugazze

Major ascent: Pian della Fugazze

- Gino Bartali: 4hr 58min 10sec

- Walter Diggelmann @ 7sec

- Giordano Cottur s.t.

- Mario Vicini s.t.

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

- Sebastiano Torchio s.t.

- Alessandro Vegetti s.t.

- Ezio Cecchi s.t.

- Michele Benente @ 18sec

- Enrico Mollo s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Fausto Coppi: 101hr 42min 48sec

- Enrico Mollo @ 3min 12sec

- Giordano Cottur @ 12min 27sec

- Mario Vicini @ 16min 59sec

- Severino Canavesi @ 17min 22sec

- Ezio Cecchi @ 23min 2sec

- Walter Generati @ 25min 35sec

- Giovanni Se Stefanis @ 28min 22sec

- Gino Bartali @ 45min 41sec

- Settimo Simonini @ 49min 9sec

20th and Final Stage: Sunday, June 9, Verona - Milano, 180 km

- Adolfo Leoni: 5hr 47min 50sec

- Gino Bartali s.t.

- Glauco Servadei s.t.

- Marcello Spadolini s.t.

- Mario De Benedetti s.t.

- Mario Vicini s.t.

- Sebastiano Torchio s.t.

- 37 riders at same time and placing

1940 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification

Bianchi

Gerbi

Gloria

Legnano

Lygie

Olympia

Groups:

U.S. Azzini-Universal

G.S. Battisti-Aquilano

S.C. Binda

Dopolavoro Bemberg

Dopolavoro Mater

Dopolavoro Az. Vismara

Il Littoriale

U.C. Modenese

S.S. Parioli

Cicli Viscontea

The Story of the 1940 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 1. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, ebook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Even with conflict raging around the world, the Giro, encouraged by Mussolini, started on May 17 in Milan. The peloton was to be almost entirely Italian except for a Belgium-Luxembourg squad that planned to ride for Ganna. The Ganna riders had even been assigned backnumbers 15 through 21, but diplomatic clearance allowing the Belgian racers to travel to Italy was impossible to secure. Walter Diggelmann from Switzerland and Christophe Didier of Luxembourg were the only foreigners who made it to Milan for the start.

Bartali, supported by his high-powered Legnano team made still stronger with the young Coppi, was favored. But Valetti’s Bianchi squad with Cinelli, Bini, Bizzi, Leoni, Vicini and Bergamaschi had to be considered nearly its equal.

Bartali’s Giro seemed to come undone by just the second stage, going from Turin to Genoa. While descending the Passo della Scoffera, Bartali hit a dog and crashed hard. Though badly hurt, Bartali remounted and gave chase. Reports about what parts of Bartali’s body were injured vary. One says he had cracked his femur, another that he banged his knee resulting in a nasty hematoma, another says he dislocated his elbow. Perhaps all are true. We’ll just accept that he was pretty well banged up. His gregario Coppi continued on and stayed with the leaders. Piero Favalli won the stage while second place was scooped up by Coppi.

Bartali rode to the finish accompanied by Vicini and Bizzi, losing 5 minutes 15 seconds. Bartali’s doctors were alarmed by the severity of his injuries and told him to abandon. The advice was ignored.

Osvaldo Bailo was now the leader with Favalli in second place and Coppi third, trailing Bailo by only 11 seconds. Valetti, Leoni, Mollo and Vicini acted like sharks in a chum-filled sea. Because they, like nearly everyone else, were unaware of exactly what Pavesi had found in the young newcomer, they concentrated their attacks on the weakened Bartali.

In the fourth stage to Grosseto, Bailo lost more than ten minutes to a big break. Gregario Fausto Coppi, who had missed the 25-man winning move, was nevertheless in second place, 1 minute 4 seconds behind Favalli (who had been in the break).

As the Giro headed north it became obvious to Pavesi that Bartali hadn’t yet recovered enough to be competitive and Coppi was indeed a superb talent who might be able to do something good in this Giro. Coppi suffered his own misfortunes including losing three minutes in the eighth stage when an accident with a car destroyed his bike. It was a sign of Coppi’s improving status within the team that Pavesi told teammate Mario Ricci to give his bike to Coppi after that eighth-stage crash.

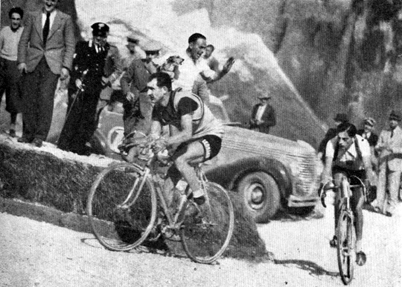

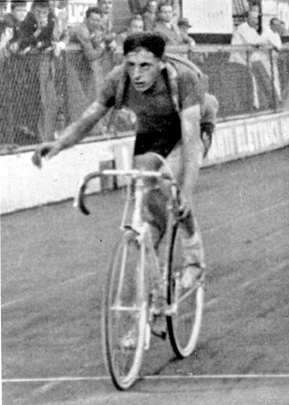

I think this is stage 10 (Arezzo - Firenze) with Fausto Coppi and Mario Vicini leading the winning break.

By the eleventh stage the neo-pro was in third place, 2 minutes 42 seconds behind Enrico Mollo. It was during this stage which took the Giro over the Apennines from Florence to Modena that Pavesi finally gave Coppi permission to attack. Bartali’s knee was still badly inflamed, making it ever more unlikely that he could be counted on to save his Giro. Besides, the new kid was riding a terrific race!

Stage eleven had three major passes, including the particularly tough Abetone ascent north of Pistoia. Here Fausto rode one of the legendary rides in cycling history as he made his way over the mountains through a cold rain, fog and snow lit up by lightning storms.

Cecchi had taken off earlier and was being chased by a powerful group that included Pink Jersey Mollo along with Coppi, Diggelmann and Bizzi. On the Abetone, Pavesi drove up next to the Mollo group and judged the time ripe for a big move. He told Coppi to attack. Coppi put in a series of attacks, each one more intense than the previous until Italy’s finest could take it no more and were forced to let him go.

Coppi flew up the Abetone, riding with that elegant ease that was to beguile writers and confound his competitors. Writer Orio Vergani saw the exhibition and said that in his lifetime he had seen the great climbers: Binda, Martano, Pavesi, Camusso, Bartali and even the first of the Tour’s King of the Mountains, Vicente Trueba, but he had never seen a man ride in the mountains like Coppi. He said Coppi was a flying eagle that knew nothing of fatigue.

Bartali was by now doing better, but a loose crank forced him to stop for a repair. He then joined in with Coppi’s chasers. With a teammate up the road he had the luxury of doing nothing more than sit in on their draft. When Coppi came into Modena alone, he was ahead of the Bartali/Bizzi chase group by 3 minutes 45 seconds, making him the new maglia rosa. Coppi was now unreservedly the team leader with Bartali and the rest of the Legnano team working for their young recruit.

Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi

Coppi’s place in the world had changed with neck-snapping speed. He had been only recently raised from the abject poverty of the child of a subsistence farmer to the maglia rosa. When asked why he was wearing black socks, he said he couldn’t afford to wear white ones because they became dingy quickly and had to be replaced. Mario Ricci assured Coppi that with the Pink Jersey on his back, he could now wear white socks.

The standings at this point:

1. Fausto Coppi

2. Enrico Mollo @ 1 minute 3 seconds

3. Severino Canavesi @ 3 minutes 46 seconds

4. Christophe Didier @ 4 minutes

5. Ezio Cecchi @ 5 minutes 13 seconds

9. Gino Bartali @ 15 minutes 4 seconds

Bartali wasn’t enjoying this Giro one bit and wanted to quit. Pavesi knew that his team leader was only twenty years old and the most challenging part of the Giro, the Dolomites, were yet to come. He counseled Bartali to stay in the race and be ready to pick up the pieces should Coppi fade.

Coppi safeguarded his precious 63-second lead over Mollo until the Giro reached the Dolomites on stage sixteen. There Coppi had his first real test. He had apparently stuffed himself with chicken-salad sandwiches before the start of the stage and when the road started to tilt skyward, both Vicini and the chicken sandwiches attacked. Coppi started to have stomach problems. Whether it was nerves or food poisoning in an era before universal refrigeration, Coppi was in crisis. By the time they confronted the second mountain pass, his stomach could take it no more. He had to get off his bike to vomit, forcing him to watch the pack and the follow cars leave him behind.

Bartali had been chasing the peloton after flatting and came across the miserable Coppi, who was still stopped by the side of the road. He started rescuing his teammate with a pep talk, telling him that the race could still be won. He gave Coppi some of his own water, talked him into getting back on his bike and got him riding back into the race.

Vicini won the stage and Mollo followed in just shy of three minutes later. But with Bartali’s help Coppi had saved his lead, finishing only four seconds behind Mollo. Bartali was a further three minutes back, but his vital work as ad hoc coach and soigneur had been done.

The next day was the tappone (the race’s hardest and most demanding stage, always in the high mountains), with the Falzarego, Pordoi and Sella passes. Pavesi famously told the owner of the café at the top of the Falzarego to have bottles of coffee ready and give them to the first two riders to crest the pass. The café owner asked who those riders would be. Pavesi told him that one would be wearing the Italian Champion’s tricolore (Bartali) and the other would be wearing the maglia rosa (Coppi). So superior were the two Legnano riders that Pavesi’s prediction came true.

Bartali leads Coppi in (I think) Stage 17.

Over the next kilometers Coppi flatted at least twice and Bartali waited for him. But on the Sella, when Bartali flatted Coppi started to take off. Pavesi stopped the impetuous youngster, telling him that certain proprieties had to be observed. Chastened, Coppi waited for his generous team captain.

There were three more stages but Coppi had the race in the bag. At 20 years 8 months 18 days, he was and remains the youngest rider to win the Giro d’Italia.

Final 1940 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Fausto Coppi (Legnano) 107 hours 31 minutes 10 seconds

2. Enrico Mollo (Olympia) @ 2 minutes 40 seconds

3. Giordano Cottur (Lygie) @ 11 minutes 45 seconds

4. Mario Vicini (Bianchi) @ 16 minutes 27 seconds

9. Gino Bartali (Legnano) @ 46 minutes 9 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Gino Bartali (Legnano)

2. Fausto Coppi (Legnano)

3. Enrico Mollo (Olympia)

Fausto Coppi wins the Giro at 20 years of age.

While Bartali was willing to give valuable aid to Coppi, his help lost some of its graciousness when he later wrote that he could have won the Giro had he not been forced to give aid to his weaker teammate. He said he didn’t give the assistance to Coppi for Coppi’s sake but for his team’s. Fair enough, he was a professional bike racer. He made his intentions clear when he predicted that in the Giro’s 1941 edition the world would again be properly ordered with Gino at the head of affairs.

It wasn’t to be. In the spring of 1940 Coppi had been called up to serve in the Italian army but was granted a 30-day deferment so that he could ride the Giro. Two days after his triumph he was told to report to his unit. On June 10, Mussolini marched his army into southern France.

Who was this extraordinary young man who had signed with Legnano in late 1939 as a promising rider and a few months later had won Italy’s greatest race?

Angelo Fausto Coppi was born to poor peasants in the little Piedmontese town of Castellania in 1919. Yes, Coppi was yet another champion from Piedmont. As a small boy Coppi found a broken, abandoned bike. He repaired the ancient machine and became so enchanted with it that he was punished for taking time off from school to go riding. To atone for his truancy, the skinny, frail-looking boy was forced to write, “I should be at school, not riding my bicycle” one hundred times.

When he was thirteen he got a job as a delivery boy for a butcher in nearby Novi Ligure, Girardengo’s hometown. As he made deliveries on his bike he met other cyclists and became interested in racing. His uncle Fausto was a bike racing fan and sprang for the cost of a real racing frame, which young Fausto built up into a bike. By the time he was fifteen he had won his first race and caught the eye of the man who would affect his career more than any other person, Biagio Cavanna.

In earlier life Cavanna had been a boxer, but gave up pugilism to become a soigneur. Cavanna was an imposing, physically large man. Given that he had worked and cared for Girardengo, Binda and Guerra, it wasn’t surprising that he was the cycling authority in the area. He set up a cycling school in Novi Ligure and with some initial hesitation, accepted Coppi as a student. Cavanna had been gradually losing his sight and by this time he was completely blind.

Cavanna taught Coppi how to train, how to eat and how to ride. Coppi was so raw that he was without even the simplest and most basic racing skills such as paying attention to the road surface to avoid getting flat tires.

Coppi progressed and by 1939 he took out a license to be an independent rider (not the same as an independent in the Giro), an intermediate level that allowed him to race with both amateurs and pros. Coppi blossomed and began to win more races. In 1939 he placed second in the Coppa Bernocchi, third in the Tour of Piedmont as well as the Tre Valli Varesine. These were fabulous placings in very prestigious races, especially for a nineteen-year-old. And that brings us to the fall of 1939 and Cavanna’s arranging Coppi’s contract with Pavesi’s Legnano team.

When Coppi reported to the Italian army, he was first sent to Limone Piemonte and later to Tortona, about fifteen kilometers north of both Castellania and Novi Ligure. At Tortona he was allowed to not only train and race, but also get coaching and massages from Cavanna.

Coppi’s 1940 autumn was just as sparkling as his spring with a series of victories that continued into the spring of 1941. He was still riding for Legnano on the same team as Bartali. The newcomer’s streak of success along with the adulation of the press was starting to stick in Bartali’s craw. Tension between the two finest riders in Italy grew.

In 1942 Coppi won the Italian National Championship, stunning Bartali by defeating him despite a flat, chasing back and overtaking the older rider. He had also become an accomplished track rider and in November of 1942 he raised the world hour record to 45.798 kilometers. That record would stand until Jacques Anquetil broke it in 1956.

A major reason Coppi did the hour record ride was to prove that he was a rider deserving of the highest international standing. With the world at war, a timed track ride was the only way an Italian in 1942 could do this. The Vigorelli Velodrome had already sustained bomb damage, so Coppi had to time his record attempt to avoid the usual noon and afternoon allied bombing raids.

In 1943 Coppi’s comfortable quasi-military life was reordered when he was sent to North Africa where he was soon taken prisoner by the British army. In 1945 the British sent him to Salerno in Italy and in April of that year he was released.