A Short History of Sachs

Part 3: Sachs Expands

by John Neugent

Tech articles | Commentary articles |

To follow this series: Sachs history part 2 | Sachs history part 4

The late John Neugent probably knew more about bicycle wheels than anyone else. Maybe more about bikes as well. He spent his life in the bike business, at every level. He owned Neugent Cycling, a firm devoted to delivering world-class equipment at the lowest possible price. —Chairman Bill

Author John Neugent

In the early ’80s Sachs decided they needed to expand. Although unknown in the US, they were a commanding brand in Europe with their sales of “gear hubs.” They occupied the high end and Sturmey Archer occupied the mid to low end. In the ’60s and ’70s Raleigh salesmen in the US (most Sturmey Archer equipped bikes were Raleighs) had to be able to assemble a 3-speed hub blindfolded, thus showing the lack of durability of the Sturmey hub.

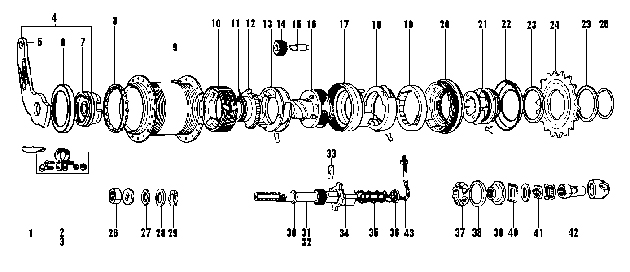

A picture that wll bring back memories to mechanics of a certain age, a diagram of the Sturmey-Archer S3C three-speed hub.

Sachs decided they need to enter the derailleur business, and to do that they needed complete groups to compete with Shimano. In the late 1980s they bought Normandy-Maillard (hubs and freewheels), Huret (derailleurs), Sedis (chains), and eventually Modolo (brakes, handlebars, stems).

The management of Sachs didn’t understand the derailleur segment of the market, and that is most likely an understatement. It’s not that they were bad managers, but they didn’t understand the market. Added to this is something I experienced many times. A company will hire someone for their expertise and knowledge and as soon as they are hired, disregard most of what they have to say. This is not uncommon, it is the norm.

There is another factor that is almost never factored into business decisions. Humans are not rational. This has been proven many times over. Yet, present an irrational plan to management and it will almost certainly be rejected. What is required is one of two things, a management team that understands the irrational aspect of the market, or a bottom up management that proves the market by example. And let’s not forget luck.

Because of the forces mentioned above, as head of their US office, I went through four bosses in five years. A well-known owner of one of the most popular cycling magazines visited our French factories and told me, on his return, that I didn’t stand a chance. I hung on largely because I was getting paid well and the work wasn’t that difficult.

But let’s get back to the individual brands, which, during my entry into the bicycle business were the leaders in their categories. One must remember that in the ’60s and early ’70s there was a bike boom going on in the US, and the US was the major market for these brands. A boom is good and bad. When there are more sales than capacity, quality tends to go down. I was a Raleigh dealer at the time and had to throw away 10% of the cranksets that came on new Raleigh bikes. I asked my salesman for some type of compensation and he said “Do you still want to be a Raleigh dealer?” The Sachs brands didn’t have quality issues but the firm more or less stopped innovating. Shimano and Suntour, on the other hand, focused on innovation to get a foothold in the market.

Nevertheless, there were bright spots. By the time I started working with Sachs, Sedis was one. Mountain Bikes had become popular and the riders burned through equipment and Sedis was acknowledged to be the leader in chains. They had two factories, one in southern France, and one in Portugal.

Sedis was our lifeline in the US. Virtually all of our income came from the sales of Sedis chains. The only major development came when we were told that Sachs didn’t own the Sedis tradename and we would have to change it (1995?). Surprisingly, when we changed it to Sachs no one cared. And maybe even more surprisingly, none of the other chain makers bought the trademark. Eventually, right before Sram purchased the Sachs Bicycle division (1997), Trek gave us a purchase order for something like one million chains. That was not our first major customer, but certainly our biggest.

In Part four, I will go into the other component divisions.

John Neugent was was one of the first to establish quality hand building in Taiwan around the turn of the century. He now owns Neugent Cycling, a firm devoted to delivering world-class equipment at the lowest possible price.