Tom Simpson and that Fatal Day on Mont Ventoux

By Les Woodland

An excerpt from Dirty Feet: How the great unwashed created the Tour de France

Back to the list of rider histories

Les Woodland has been kind enough to let me excerpt a chapter from his book Dirty Feet: How the great unwashed created the Tour de France. You can learn more about this engaging and fact-filled book which is available in print, Kindle eBook and Audio Book versions, by clicking here. Or, just click on the Amazon link on the right to get your copy.

Les Woodland writes:

The last ride that Tom Simpson made was from the village of Bédoin in eastern France towards the top of the mountain from which the village makes its living. Unless you are a naturist visiting the campsite there, there is little other reason to go than to try your hand on Mont Ventoux. Hundreds of nameless cyclists do it every weekend. At one end of the slope through the small town is a bike shop that sells socks embroidered with the mountain’s name. At the other are a succession of bars and restaurants. Cyclists sit outside many of them, happy to have reached the top of the mountain or wondering whether to put off climbing it until another day.

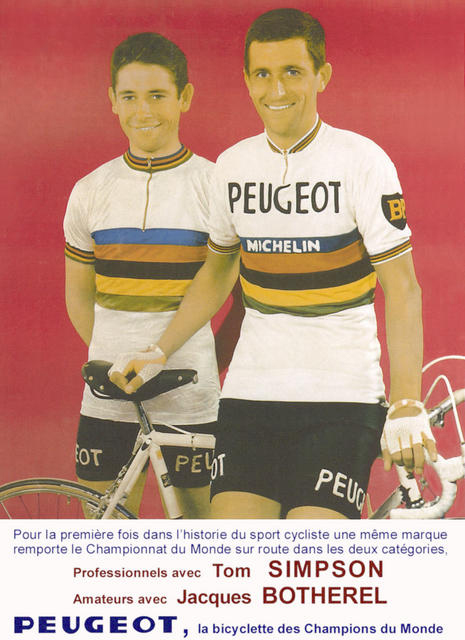

Tom Simpson had won the World Championships in 1965.

One of those bars is the Observatoire, named after the astronomy centre at the mountain’s peak. The café has red awnings, a spread of tables and cushioned wooden chairs outside and, above the awnings, three wide windows set in brown wooden frames, slightly inset and curved at the top. There is nothing there to say so but it was from that bar that Tom Simpson got his last illicit drink of the 1967 Tour de France. He had set out after a disappointing season the previous year to show he was the superman that his British fans believed him to be and because, more prosaically, Daniel Dousset had told him his contract price would be hopeless if he didn’t make a name in the Tour. “He set out that year to win the Tour de France,” his wife Helen said in a BBC radio documentary twenty years after the day.

In the middle of 13 July 1967, Colin Lewis arrived at Bédoin beside Simpson, his leader and room-mate. He knew that Simpson wouldn’t be in his company much longer. Simpson was a practised professional, Lewis a weekend part-timer back home in Devon and, effectively, riding the Tour de France in his holidays. His job that day was to run Simpson’s errands, which in Bédoin meant raiding the Observatoire for whatever he could steal. He joined the other riders in their plunder and came out with a bottle of Coca-Cola and four others he hadn’t had time to check. It wasn’t his first raid. A photo of the same Tour caught his Condor bike lying on the road outside a bar from which other riders were escaping with their booty.

“I stuffed three of them into my back pocket and the other down the back of my neck,” he remembered. “Out of the bar, I worked my way through the convoy and back to the peloton. Tom was my major concern and I gave him the Coca-Cola, which he was really pleased about. He took a long drink and handed it to the next guy.” Simpson asked what else Lewis had. Out came a small bottle of brandy. Simpson said it would help settle his stomach and he took a swig and threw the bottle over a hedge and into a field of sunflowers.

Go to the Observatoire now and they will tell you the story, the chasse à la canette and its circumstances, the significance of which they found out only later. Many reports say it was Simpson himself who raided the bar but that was confusion of white jerseys with their Union Jack on the shoulder and because for the rest of the year Simpson rode in the white jersey of the Peugeot team. Stars didn’t do the dirty work themselves. Just as when van Looy ordered Vin Denson to find him a café, they got their lesser riders to do their bidding for them. Had Simpson stopped then, in all probability the others would have attacked. He wasn’t an obvious contender for the overall victory but they would miss no chance to push him down the list.

Simpson was adventurous in races, often beyond the point of rashness. But his light build made him best at races up to a week, whereas the Tour lasted a month. He was light enough to ride wheels with twenty-eight spokes, usually chosen for the track, where others preferred thirty-six. That lightness was an advantage on long but not devastating climbs like Mont Ventoux. It is 22 kilometres from Bédoin to the observatory 1,622 metres higher, though the first kilometres rise only gently. The rest is steep and grinding, with ramps of nearly eleven per cent. The problem in summer is the heat, because for two thirds of its rise it passes through fly-ridden woods that hog the air. Doubtless with colour and imagination thrown in for the same price, Antoine Blondin, the most literary of cycling writers, wrote: “There are few happy memories of this sorcerer’s cauldron. We have seen riders reduced to madness under the effect of the heat or stimulants, some coming back down the hairpin they thought they were climbing, others brandishing their pumps and accusing us of murder… falling men, tongues hanging out, selling their soul for a drop of water, a little shade.”

Whether riders or anyone else took that story seriously, they all knew that a French rider, Jean Malléjac, had collapsed on the mountain in 1955 and been put in an ambulance with his legs still pedalling a bike that was no longer there. He was “streaming with sweat, haggard and comatose, zigzagging, and the road wasn’t wide enough for him,” the Tour archivist, Jacques Augendre, remembered.

Malléjac never denied that he was drugged, only that he had drugged himself. The dope had perhaps been in a bottle handed up by a soigneur, he thought in a television interview two days before Simpson’s death. Other riders were less cynical. If they needed drugs to get up Mont Ventoux, at racing speed for the front men or simply to get up at all for the rest, then many of them would take them. It was in the culture. They just hoped they’d be luckier than Malléjac.

VOICES FROM THE PAST

You would have to be naive or a hypocrite to insist that the Tour de France, Bordeaux–Paris, Dauphiné Libéré, can be ridden on just mineral water… All the riders take something.

—Jacques Anquetil in a television debate with François Misoffe, the sports minister, 1967VOICES FROM THE PAST

Personally, I take stimulants and I don’t hide it. But people lump it all together—drugs, doping and stimulants—without knowing what they mean. All riders need stimulants.

—Jacques Anquetil, Miroir Sprint, 9 May 1966

Simpson said of Mont Ventoux that “it is like another world up there among the bare rocks and the glaring sun… I think it was the only time that I have got off my bike and my pants have nearly fallen down. They were soaked and heavy with sweat which was running off me in streams and I had to wring out my socks because the sweat was running into my shoes.”

Twenty kilometres after swigging his brandy, Simpson lay white and inert by the roadside. He had fallen once, got back on and struggled a little further before Harry Hall, the mechanic, ran from his car and grabbed him before he rode groggily off the side of the unprotected road and into the ravine. The Tour’s doctor, Pierre Dumas, who for some years had led an international protest against drug-taking, clamped an oxygen mask over Simpson’s face. One of the two police helicopters escorting the Tour landed at 4:40 p.m. to take Simpson away. It looked, said a television commentator, like a black vulture as it turned and flew off towards Avignon. In it, Dumas’s assistant, Ferrocio Macorig, took turns with a nurse in massaging Simpson’s heart.

Tom Simpson (left, front) in crisis on Mont Ventoux

Simpson’s jersey held three small tubes, two empty and one labelled as containing Tonédron. Dumas felt them in his pockets as he began lifting Simpson’s jersey to bare his chest for heart massage. He took them out at the hospital and gave them to the police team that had started to gather. Police found more drugs in Simpson’s luggage.

VOICES FROM THE PAST

We had heard that Tom was up with the leaders climbing the Ventoux. Then as we accelerated ahead down the tricky descent ahead of Jimenez, the reports began to come through again with no mention of Tom. Only when we reached the finish to await the riders did we learn that he had fallen, assuming it was a crash. Then the team car came in and we knew that he had collapsed, but still with no inkling that the end was to be so tragic… Gradually the rumours grew, defying belief, until we had the official announcement.

—Sid Saltmarsh, Cycling, 22 July 1967

The autopsy decided that Simpson had died of heart failure caused by exhaustion, dehydration and heat. The report added that “the amount of amphetamine that Simpson took could not have killed him by itself but it could have led him to go beyond his limits.” It was just that that Jim Manning had written. The British Cycling Federation racing secretary, Bryan Wotton, said so many calls came into the offices in sedate Park Crescent on the edge of London’s Regent’s Park that there was no time to think of anything else, let alone an inquiry. The autopsy records in France were filed, the case closed and the paperwork eventually thrown away.

VOICES FROM THE PAST

A champion, he wanted victory too badly, with all that it could bring to his happiness as a father and husband. We often asked ourselves if this athlete, who at work so often appeared in pain, had not committed some errors in the way he looked after himself. Doping? We can fear the public revelation of a tragedy caused by this scourge.

—Jacques Goddet, L’Équipe, 14 July 1967

More than half a century after his death, Simpson still rides the races of old men’s memories. There are websites and internet discussion groups in his memory. Advertising a film in which Simpson appears guarantees an audience. To modern riders he is as distant as mini-skirts, radio stations on the North Sea and teenagers who said “fab” and “groovy.” Even Cycling Weekly (or just plain Cycling as it was in Simpson’s day) can’t bring itself to acknowledge what he achieved. He is remembered not for his victories but for the day of his death and the way it revealed him, along with the sport in which he made his living, as a drug-taker. It named not Simpson as its man of the century in 2001 but the track rider Chris Boardman, breaker of the world hour record but never once a finisher in the Tour de France nor a world champion on the road. The debate filled the magazine’s letters pages for weeks, as no doubt the magazine hoped.

Simpson is remembered now by the memorial on the mountain and by a little-known museum in the Harworth village of Nottinghamshire where he was buried beneath a black marble stone that carries the message “His body ached, his legs grew tired, but still he would not give in.” Nearby is the Harworth and Bircotes sports club and, in it, a small collection of Simpson memorabilia. His white Peugeot bike is there, though not the one he rode in the Tour but the one on which he won Paris–Nice in 1965, along with his Tour de France white jersey with its Union Jack on to each shoulder. It’s when you see that jersey, and those kept by his friend Vin Denson, that you understand how shallow-chested Simpson was. “We often used to laugh at Tom in the showers,” Denson says, convinced that his pigeon chest was the result of generations of mining and marvelling that it could ever have held enough air.

Did you find this story interesting? There is lots more in Dirty Feet: How the great unwashed created the Tour de France