Tom Simpson

by Owen Mulholland

Les Woodland's book Tour de France: The Inside Story - Making the World's Greatest Bicycle Race is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Owen Mulholland writes:

The specter of doping has haunted cycling. From bike racing's earliest days "the bomb" was always there to save a rider from his weakening self. In Europe it was an open secret. Even amateur riders toted around enough pills and vials and syringes to establish a small pharmacy. Some or these unidentified products may well have been vitamin supplements, but as for the rest ...

Victor Vincente (né Mike Hiltner), the first American in this century to win a road race in Italy, told me how he was once so amped up that even after a severe crash into a stone wall, he just babbled away while en route to the hospital in the ambulance

In retrospect, doping has provided the annals of cycling with some of its more amusing moments. There was, for instance, the case or Abd-el-Kader Zaf, a member of a professional North African team in the 1950 Tour de France. (Most of northern Africa was colonized in those days). On a boiling hot stage from Perpignan to Nimes Zaf broke away with a French rider. After establishing a good lead, Zaf began to weaken and finally collapsed under a tree where a local paisan tried to revive him with ample doses of red wine. Delirious from the heat, the effort, the drugs he'd taken, and the wine, he didn't come-to until he'd been carted off to a hospital. Finally realizing his situation he demanded that he be taken back to the roadside where he'd been picked up so he could ride the kilometers over which he'd been driven! Of course the time limit for the stage had long since elapsed and no amount of riding could save his elimination from the Tour

1966: Tom Simpson (far left) with Jacques Anquestil, Rudi Altig & Eddy Merckx.

But the incident that really made the issue inescapable was the death of Tom Simpson in the l967 Tour. Only then did the authorities finally wake up to the fact that this was a matter of life and death. Of course just what is dope and what is acceptable scientific preparation has remained a hot debate right to the present day. The post-Olympic blood doping furor was one of many recent incidents which show how sticky the issue is.

However, there is an end of the continuum that leads from mineral water to human super-charging where all can agree certain substances must be banned. Taken in sufficient amounts, amphetamines have the ability to override the body's built-in safeguards. Quite simply, that is what happened to Tom Simpson on the most tragic day in our history, July 13, l967.

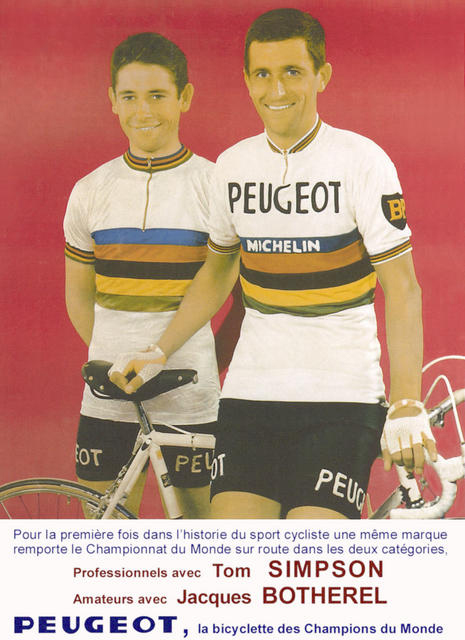

To this day, Simpson remains the greatest road rider England ever produced. Arriving in France in 1959, he quickly climbed the rungs of the continental professional ladder: 1960 - coming close to winning Paris-Roubaix; 1961 - a victory in the Tour of Flanders; 1962 - maillot jaune for a short time in the Tour de France; 1965 - World Champion.

Tom Simpson in the World Champion's Rainbow Jersey

Such achievements would have satisfied many riders, but Tom still dreamed of the ultimate, victory in the Tour de France. His brilliant but occasionally fragile constitution always seemed to let him down on some mountain stage. But hope springs eternal and 1967 began auspiciously.

He got off to a great start by winning Paris-Nice, the week long "race to the sun" in March. One of the men over whom he showed clear superiority was an up and coming young rider beginning his third season on the professional circuit. His name was Eddy Merckx.

As always, the Tour loomed as the centerpiece of Tom's season, and he wasn't enthralled when the organizers decided to revert to the old time formula of national teams. All through the season riders compete for their trade team sponsors, in Tom's case, Peugeot. Now the riders were supposed to forget all about those commitments and race for their respective countries. A small group of home grown English pros with almost no continental experience were all Tom could look to for teammates. He knew he would be on his own.

His game plan, therefore, was to ride cautiously on the flat and save himself for the mountains where the big time gaps would make all the difference. The 1967 Tour followed a clockwise direction across northern France before dropping south through the Vosges and Alps. Simpson survived these tests fairly well, although he'd had to put down the hammer very hard on several occasions.

July 13 began in Marseilles, and as he awaited the call to the line a Belgian journalist noted that Tom looked tired and asked if it was the heat. "No, it's not the heat." Tom replied. "It's the Tour." As events were to prove, this was a telling comment.

Still the heat could not be ignored. Already it was approaching 80 F in the old port city, and many riders winced at the thought of what lay before them. 100 was quite possible, and there was no protection whatsoever on the rocky face of Mt. Ventoux which they were scheduled to tackle around two in the afternoon.

The long approach slope to the base or the "Giant of Provence" (as Mt. Ventoux is known locally) served to shred the field and leave the big guns clustered at the front. Simpson, as expected, was the only member of his team to be in this group. After seven miles of grueling toil Tom began to slip back to a group of chasers about a minute behind. In that group was Lucien Aimar, the '66 Tour winner. He remembered how Tom hadn't been content to sit in the group, but kept trying to bridge the gap back up to the front bunch. But no matter how hard he tried, Tom simply could not maintain the tempo necessary to move up.

Suddenly Tom dropped from his little cluster of riders. Barely able to turn the pedals he began to weave across the road. In a hundred yards he collapsed. Immediately he was surrounded by spectators, and to them he appealed, in whispered gasps, "Put me back on my bike." These were to be his last words.

Tom Simpson (on left) in his final minutes.

The well-meaning fans lifted him onto the saddle and got him going with a good push. When the momentum dwindled in a few feet Simpson began his former zigzag course. Another hundred yards and Tom again tottered from the bike, this time utterly spent. He immediately lapsed into a coma and nothing the Tour doctor or a local hospital (where he was taken by helicopter) could do brought relief. In three hours Tom Simpson was dead, victim of his own indomitable will and the sorcery of his supposedly magical pills.